Fran Shor

Gone to Croatan (review)

Power and Its Refusal in Early America

1994

a review of

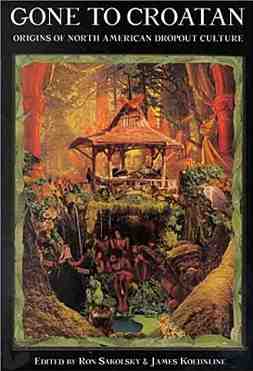

Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American Dropout Culture, ed. Ron Sakolsky and James Koehnline, 382 pp. Autonomedia, New York, 1993, $12.

“(T)here is no single locus of great Refusal, no soul of revolt, source of all rebellions, or pure law of the revolutionary. Instead there is a plurality of resistances, each of them a special case: resistances that are possible, necessary, improbable; others that are spontaneous, savage, solitary, concerted, rampant, or violent; still others that are quick to compromise, interested, or sacrificial.”

—M. Foucault

Foucault’s reminder that there are multiple strategies of revolt is aptly illuminated in Gone to Croatan. This anthology of essays and poetry highlights the refusal of indigenous peoples and insurgent forces to co-exist with the power of the emerging American colonial and imperial state.

Gone to Croatan takes its title from the disappearance of the first wave of European colonists in early 17th century Virginia who apparently “dropped out” by abandoning their settlement and joining the Croatan Indians. As Ron Sakolsky’s introduction contends, these Europeans “were challenging the newly constructed boundaries between wilderness and civilization, and, in so doing, were rocking the freshly laid colonial foundations of North America.”

The essays contained in the anthology “seek to celebrate the spark of-transgression by examining some compelling examples of those who have ‘dropped out’ of the striated grid of dominant Euro-American society, whether by original acts of refusal, by fanciful choice or by dire necessity.”

Foremost among those who responded out of dire necessity to that “striated grid” were the indigenous people of North America. In essays and poems by and about American Indians and their acts of resistance, one sees a continuing challenge to the imperial and desacralized values of civilization’s obsession with power and destruction of the wilderness.

In recounting the occupation of Alcatraz Island by Native American activists in 1969–1970, Jack D. Forbes quotes at length from a Cherokee participant’s excoriation of what white civilization has wrought on the North American continent:

“They have wiped out forests, destroyed grasslands, turned deserts into dust-bowls, and seriously diminished almost every other natural resource. What are their characteristics? Igana-noks-salgi. Those who are greedy for land, the old Creek Indians called them. They are always gobbling up land, taking it from Indians, Mexicans, or less successful white people.

“They are always looking for gold, for uranium, for oil, for more profits, for new real estate deals, for better-paying jobs, for a new place to live.

“...They are crazy—driven, restless, dissatisfied—but it is to get that they are crazy. Of course, many are crazy to spend, to display, to show-off, but this need for consumption only serves to make the getting all the more important.”

In denouncing the “getting-crazy people” this fanciful but accurate account by “Injun Joe” locates the historical swarming of the continent by “restless, aggressive, materialistic, scheming, proliferating white people who like to break laws, don’t respect other people, and consider themselves to be the New Israelites, God’s chosen people, destined to get whatever they want.”

Still, Indians sought ways of resisting and holding back the tide of “getting-crazy people.” In Rachel Buff’s provocative essay on Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (“Gone to Prophetstown: Rumor and History in the Story of Pan-Indian Resistance”) she asserts that “Indians in this period (the early 19th century) adopted a strategic identity.”

Such a Pan-Indian identity, expressed through the visionary preachings of Tenskwatawa (the great Shawnee prophet), offered “a political and cultural alternative to colonial domination.” Even though Buff’s essay highlights why such a Pan-Indian identity was necessary to rally various Indian nations against the onslaught of white settlers at the beginning of the nineteenth century, her efforts to apply the sophisticated theories of post-colonialist studies often confuse the discussion beyond her earlier description of the Shawnee struggle as a cultural revitalization movement.

Ethnic Exclusion

Other essays suggest the trans-cultural identity on the part of Native Americans was malleable enough, for example, to include runaway slaves among the Seminoles. They and others developed an eclectic and miscegenated identity that threatened the racist order of ethnic exclusion and inclusion. There were also instances when Indian practices and beliefs provided inspiration for white settlers, from Croatan to the present time.

However, in an essay departing from the “dropping out” focus of the anthology, a case is made for how 19th century suffragists were inspired by the prominent roles Iroquois women performed within their communities. In using the example of Iroquois women to argue for an extension of white women’s civil and political rights, the essay by Sally Roesch Wagner is out of place in a volume dedicated, as articulated in Ron Sakolsky’s preface, to “rejecting pseudo-oppositional remedies.”

That Native American culture inspired Euro-Americans over the centuries to seek out paths of resistance is evident in other essays. In “Lost Ancestors: An Introduction to Pooch Van Dunk’s ‘Indian Heritage,’” Peter Lamborn Wilson cites how the historical struggles of Indians to achieve sovereignty also “implied the rejection of mainstream America with all its racism, oppression, and boredom—its war and its ‘Prison of Work.’”

In other essays, most notably Hugo P. Learning’s “The Ben Ishmael Tribe: A Fugitive ‘Nation’ of the Old Northwest,” there is a fascinating portrayal of the 19th century tri-racial nomadic tribe known as the Ishmaelites whose “opposition to the accumulation of wealth, detestation of the laws of the majority society, and advocacy of the free use of land” put them into constant conflict with their Indiana neighbors.

Mainstream abhorrence of this drop-out community reached hysterical heights in the late 19th century with the pseudoscientific and racist labeling of the Ishmaelites as “hereditary misfits” because of their “nomadism and avoidance of wage labor.” In their desire for freedom and autonomy, the mere taint of Indian cultural values was enough to put such tri-racial tribes at risk.

This subversive tradition continuously emerged throughout colonial history from Thomas Morton’s May Pole carnival to early communal experiments. Several essays consciously link these efforts to both a tradition of cultural and political resistance and to a continuing concern for seeking alternatives to the oppression and exploitation embedded in American society.

“Motley Crew”

Clearly, such a spirit of political rebellion was alive in 18th century America, especially as a backdrop and follow-up to the American Revolution. In the longest, most scholarly, and most exhilarating of the essays in this collection (“The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves and the Atlantic Working Class in the Eighteenth Century”), Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh investigate how a “multi-racial, multi-ethnic, transatlantic working class” shook the ports on both sides of the English Atlantic with their acts of resistance and insurrection. The authors identify this “motley crew” as the key proletarian formation of the period. However, their sensitivity to the multiplicity of resistances is evident in the following concluding remarks to their essay:

“We can begin to see how the events of 1747, 1768, 1776, and 1780 were part of a broad cycle of rebellion in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, in which continuities and connections informed a huge number and variety of popular struggles. A central theme in this cycle was the many-sided struggle against the confinement—on ships, in workshops, in prisons, or even in empires—and the simultaneous search for autonomy.”

The search for autonomy and freedom in late 18th century America led directly to anti-authoritarian struggles from the American Revolution to rebellions in the early republic. David Porter’s survey of “‘Anarchy’ in the American Revolution” illuminates the tensions between “republican elitists (who) argued for stronger central authority” and those forces that sought “decentralization, circulation of leaders, and greater accountability.” While Porter is aware of the contradictions within those decentralizing forces who wanted to seize more Native American land, he too easily assumes the anti-authoritarian tendencies of local forces can be construed as inherently anarchist.

A similar assumption underlies Paul Z. Simons’ interpretation of Shays’ and the Whiskey Rebellions in late 18th century Massachusetts and Western Pennsylvania, respectively, in “Keep Your Powder Dry: Two Insurrections in Post-Revolutionary America.” Here, the frequent use of the concept of “autonomy” tends to blur any distinction between an ideology of possessive individualism and one of anarchism.

Simons admits such “localist sentiment of the early Americans” could imply both what he describes as right and left tendencies, but he too quickly discounts how localist sentiment could be mobilized later for states’ rights and defense of slavery. It is not enough to cite examples in American history of the “essential right of insurrection” as Simons does in this essay if the contradictory dynamics of insurrections, fetishizing of violence, possessive individualism, and macho politics, not to mention the paranoid delusions of present day right-wing survivalists, is part of that history.

While Porter and Simons, along with other essayists in the volume, attempt to trace the legacy of anarchy and insurrection throughout American history in order to reclaim a radical tradition, there is too little recognition of its inherent contradictions.

Certainly, there is a more nuanced argument than one finds in David DeLeon’s earlier book, The American as Anarchist, where he argued that “the black flag has been the most appropriate banner of the American insurgent.” Nonetheless, elevating a visceral anti-institutionalism to the level of self-conscious anarchist or even insurrectionary politics, as DeLeon, Porter, and Simons seem to do, overlooks how such politics were (and are) still implicated in repressive politics of race, gender and empire.

To say this is not to invalidate these movements or to cast a pall of white-skin male privilege on each and every activity of early radicals. However, historian Barbara Jean Fields makes clear in her work on the emergence of the ideology of race in 17th century Virginia, even where such insurrectionary activities like Bacon’s Rebellion brought together poor whites and blacks against the political and mercantile elite, another oppressed group, namely Native Americans, became victimized.

Moreover, in the crazy patch-quilt of the history of that time, the result of Bacon’s rebellion helped whites to gain political rights at the expense of the African-Americans who were further chained with the emergence of the slave codes of colonial America. Thus, locating some “pure law of the revolutionary” in any of the past insurrectionaries and drop-outs must be constantly held up to scrutiny and skepticism.

In considering what is usable and exemplary American history, Croatan admirably brings that scrutiny and skepticism to bear against the official falsifications and obliterations of the past. While containing its own contradictions and confusions such as rendering an almost exclusively male face to the communal uprisings and resistances chronicled, Croatan nevertheless presents “a plurality of resistances” from the past to inspire us in the present and future.

If we are no longer convinced about what constitutes the right strategy and practice for a way out of the degradations and insanities of contemporary civilization, we can be consoled by Foucault’s insight that “there is no single locus of great Refusal” and Sakolsky’s statement from the introduction, that if “we can question the division of our world into the categories of ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism,’ then we have begun to question all forms of hierarchy.”

FE Note: Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American Dropout Culture, ed.: Ron Sakolsky & James Koenline is available from our book service. Please see book page.