Various Authors

Our Fallen Anarchist Comrades

Remembering Albert Meltzer, Valerio Isca, Alfredo Monrós, Richard “Tet” Tetenbaum, Earnest Mann, and Jim Gustafson

Albert Meltzer

Born London, Jan. 7, 1920; died, Weston-Super-Mare, N. Somerset, May 7, 1996.

Albert Meltzer was one of the most enduring and respected torchbearers of the international anarchist movement in the second half of the twentieth century. His sixty-year commitment to the vision and practice of anarchism survived both the collapse of the revolution and civil war in Spain and World War II. He helped fuel the libertarian impetus of the 1960s and 1970s and steer it through the reactionary challenges of the Thatcherite 1980s and post-Cold War 1990s.

Fortunately, before he died, Albert managed to finish his autobiography, I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels (AK Press), a pungent, no-punches-pulled, Schvejkian account of a radical enemy of humbug and injustice.

A life-long trade union activist, he fought Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts in the battle of Cable Street, played an active role in supporting the anarchist communes and militias in the Spanish Revolution and the pre-war German anti-Nazi resistance, was a key player in the Cairo Mutiny during World War II, and helped rebuild the post-war, anti-Franco resistance in Spain and the—international anarchist movement.

His other achievements include the founding of the Anarchist Black Cross, a prisoners’ aid and ginger group and the paper which grew out of it—Black Flag. However, Albert’s most enduring legacy is the Kate Sharpley Library, probably the most comprehensive anarchist archive in Britain.

Born in 1920 in the London of Orwell’s Down and Out, Albert was soon enrolled into political life as a private in the awkward squad. His decision to go down the road of revolutionary politics came, he claimed, in 1935 at the age of 15 as a direct result of taking boxing lessons. Boxing was considered a “common” sport, frowned upon by the governors of his Edmonton school and the prospective Labour MP for the area, the virulently anti-boxing Dr. Edith Summerskill.

Perhaps it was the boxer’s legs and footwork he acquired as a youth which gave him his lifelong ability to bear his considerable bulk. It certainly induced a lifetime’s habit of shrewd assessment of his own and his opponents’ respective strengths and weaknesses.

The streetwise, pugilistic but bookish schoolboy attended his— first anarchist meeting in 1935 where he drew attention to himself by contradicting the speaker, Emma Goldman, with his defense of boxing. He soon made friends with the aging anarchist militants of a previous generation and became a regular and dynamic participant in public meetings.

The 1936 anarchist-led resistance to the fascist uprising in Spain gave a major boost to the movement in Britain, and Albert’s activities ranged from organizing solidarity appeals, producing propaganda, working with Capt. J.R. White to ship illegal arms from Hamburg to the CNT in Spain, and acting as a contact for the Spanish anarchist intelligence services in Britain.

Albert’s early working career ranged from fairground promoter, a theatre-hand and occasional film extra, including a brief appearance—in the Leslie Howard, anti-Nazi film, “Pimpernel Smith.” The movie did not follow the usual wartime cinema line of victory over Hitler, but rather of revolution in Europe.

The plot called for showing Communist prisoners, but by the time Howard made the film in 1940, Stalin had invaded Finland, and the script was changed to anarchist prisoners. Howard decided that none of the actors playing the anarchists seemed authentic and insisted that real anarchists, including Albert, be used as extras in the concentration camp scenes.

Albert’s later working years were spent as a second-hand bookseller and, finally, as a Fleet Street copytaker. His last employer was, strangely enough the mainstream Daily Telegraph.

Albert’s championing of class-struggle anarchism, coupled with his skepticism of the student-led 1960s New Left earned him his reputation for sectarianism. Paradoxically, as friend and Black Flag cartoonist Phil Ruff points out in his introduction to Albert’s autobiography, it was the discovery of class struggle anarchism through Black Flag’s “sectarianism,” under Albert’s editorship, that convinced so many anarchists of his and subsequent generations to become active in the movement.

To Albert, all privilege was the enemy of human freedom, not just the privileges of capitalists, kings, bureaucrats and politicians, but also the petty aspirations of opportunists and careerists among the rebels themselves.

It is difficult to write a public appreciation of such an inscrutably private man. Much of what he contributed to the lives of those who knew him must go unrecorded, but he will be remembered fondly for many years to come by those of us whose lives he touched.

— Stuart Christie, PO Box 35, Hastings, East Sussex, TN34 2UX, United Kingdom

Fifth Estate note: Friends of Albert Meltzer have launched The Meltzer Press to continue the work of their departed comrade. They will collaborate with the Kate Sharpley Library to publish new and out-of-print libertarian texts. The first offering is Juan Busquet Verges’ Sentenced to Death Under Franco. For info write The Meltzer Press, PO Box 35, Hastings, East Sussex, TN34 2UX, England.

Valerio Isca

December 22, 1900-June 13, 1996

Valerio’s friends remember him as all heart, tenderness and love. He remained steadfast in his commitment to anarchist principles from the time, as a recent immigrant from Italy in the 1920s, he became involved in the defense of Sacco and Vanzetti.

It was in anarchist circles that he met his companion of fifty years, Ida Pilat. Ida was a skilled translator from and into French, Spanish, German and Yiddish and her contributions appeared in numerous North American and European anarchist publications. Ida died in 1980. She and Valerio worked to prevent the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, but the state exercised its vengeance in 1927.

They both were energetic members of the Libertarian Book Club in New York City. It was founded in 1945 and was one of the most active anarchist groups during the post-Second World War years. The group published important anarchist texts and maintained a mail order book service.

Valerio was close to the group of North American Spanish anarchists, Cultura Proletaria, for whom the Spanish Revolution was a significant event. After Franco’s 1939 military victory, they devoted themselves to saving prisoners in fascist jails. They also kept the anti-Franco struggle alive and assisted Spanish emigres in French concentration camps.

Valerio and Ida built a house in the anarchist Mohegan Colony where Rudolf Rocker and his family lived. They were comrades as well as neighbors and Valerio remembered with pride how he was instrumental in having Rocker’s classic Nationalism and Culture published in Italian.

Valerio was a living history book of the anarchist movement and could relate names and details of events with great precision. He was an excellent photographer and left an archive of the photographs of friends and comrades he met throughout his long life.

Valerio was keen-witted and alert until the end and his generosity and warm-heartedness were evident upon meeting him. Several years ago he visited us at the Fifth Estate office and everyone present still cherishes the memory of that afternoon.

—F.A.

Alfredo Monrós

April 12, 1910-Sept. 28, 1995

The death of Alfredo Monrós in Montreal saddened us at the Fifth Estate. Born in Spain, Monrós and his family emigrated to Montreal in 1951.

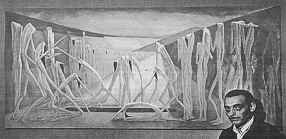

For 50 years his artistic work furthered the anarchist and anti-fascist movements. Monrós is best known for his drawings, which can be found in numerous anarchist journals and books, including the cover of Jose Peirats’ Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution published at Detroit’s Printing Co-op.

A famous Monrós drawing was used to protest the 1963 death sentences of Joaquin Delgado and Francisco Granados by the Franco regime in Spain. The method of execution was the garrote, a device which strangles the victim. Posters of the Monrós drawing depicting horrifying figures of an executioner and his victim were paraded at Spanish embassies across Europe and North America.

A reprint of the image, also done at the Printing Co-op, was used in 1974 when Salvador Puig Antich was garroted in Barcelona and Heinz Chez in Tarragon for their anti-fascist activity.

The loss of a friend and comrade is always painful, but his legacy impels us to keep on fighting for our cause. ¡Salud Alfredo!

—F. A.

Richard “Tet” Tetenbaum

Richard “Tet” Tetenbaum, a linchpin of the San Francisco Anarchist community, died of cancer on June 2.

Tet was active in a variety of anarchist attempts—to create community spaces, and an activist who lived anarchism in his personal life. He shunned traditional forms of wage labor whenever he could, but was a-hard and dedicated Worker for the things he believed in.

Tet was involved with most of the San Francisco anarchist community’s major ongoing projects. He was one of the founders of Bound Together Anarchist Books, where he worked for 20 years. Tet was one of the few people deeply respected by the various anarchist communities—in the Bay area, and his death brought together, (at least for a few hours) many people who despised each other’s politics.

The day after he died, 200 of his comrades gathered to pay tribute to him. We told stories about his life and recounted our experiences with him.

Tet drove a taxicab which gave him opportunity—to do something he really loved—talk with people. On a number of occasions, he would bring a receptive passenger by Bound Together in the middle of the night to show them anarchist literature.

One person recounted how, when he came to San Francisco, Tet seemed to be everywhere: “When I was shopping at my collective community foodstore (the Inner Sunset) Tet was behind the counter; when I looked for information at my local anarchist bookstore, Tet was there, and when I had to catch a ride somewhere Tet seemed to always pass by in his cab-and offer me a lift.”

Another person told the story of sailing with Tet under the city’s July 4th fireworks and being confronted by police speedboats. “The cops were surprised that we didn’t obey their requests to leave the area and that we didn’t appear frightened of them. They didn’t realize that we had been-disobeying orders from authority figures all our lives.”

Tet spent his final weeks in a hospice, surrounded by caring friends. Though his parents and relatives initially wanted him placed in a hospital, they were moved by the emotional support shown by his comrades and realized how important it was—for him to be in a non-institutional setting.

As his condition deteriorated, his immediate family thought Tet should be protected from the constant stream of visitors and suggested drawing up a list of people authorized to see him. However, even at the edge of death, Tet would not create a hierarchy among his many friends. Those of us from his’ extended family of comrades feel our visits sustained him in his final days.

Tet had ambiguous feelings about having to sell—books in order to keep Bound Together open. He was the kind of person who, seeing someone stealing a book, would say, “‘As long as you’re planning on reading it, go ahead and take it.”

—Howard Besser

Earnest Mann

Although half-mast flags in April marked the death—of U.S. Commerce Secretary Ron Brown—our thoughts instead were on Ernest Mann, editor of what must have been the longest running zine in existence, the Little Free Press.

The 69-year-old Mann was bludgeoned to death in March by his teenage grandson who then took his own life. The two had been living together in a Little Falls, Minnesota, trailer court.

A former successful real estate investor, Mann dropped out in 1969 to live a contemplative life and promote his quixotic “Priceless Economic System.” Described as “definitely the most idealistic, and arguably the most naive set of pamphlets” (High Weirdness By Mail, Stang 1988), the Little Free Press was part crusade, part autobiography about squirrel trapping, raft building, and grandson raising.

Mann first received regional attention in 1978 when Minneapolis Tribune columnist Larry Batson wrote about his quest to promote freedom. By the time the-national media noticed him he was already widely known throughout the zine network via Mike Gunderloy’s Factsheet Five which reviewed Little Free Press #41 in 1982.

Thirteen and a half years later, Mann was still at it, pumping out issue #138 and visualizing “peace on Earth and goodwill.” Profoundly human, ‘an enjoyer of books and simple-pleasures, an anarchist and atheist, who never ceased his one-person utopian experiment, he will be missed.

Mann’s writings are compiled in his self-published I was Robot (Utopia now possible).

—Chris Dodge

Jim Gustafson

Detroit poet Jim Gustafson died Oct. 24 at the age of 46 from a brain hemorrhage. Jim was never housebroken; he was a constant irritant to polite society and a constant amazement to those who knew him.

Jim authored several books and appeared in various anthologies, including a recent collection, Up Late, edited by Andrei Codrescu. He appeared in Paris Review, Rolling Stone, Exquisite Corpse, the Fifth Estate, and other publications.

Gustafson wrote his own epitaph: When I die, I just want / a jukebox for a tombstone / and to leave all my friends / rolls of quarters.

—Ken Mikolowski