Fifth Estate Collective

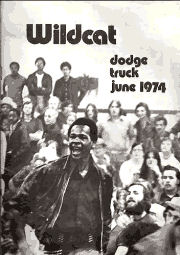

Wildcat: Dodge Truck, June 1974

...30 years later

This year marks the 30th anniversary of publication of the pamphlet Wildcat: Dodge Truck, June 1974, written and produced by several of the people who became the core of the Fifth Estate collective the next year when it was transformed into an overtly council communist, and then, anarchist publication. A short excerpt is reprinted below.

The wildcat strike at an obscure Chrysler production facility in suburban Detroit occurred amidst the generalized spirit of rebellion of the early 1970s that had seeped far deeper into society than what is usually characterized as an era of college and youth-centered protest. The pamphlet tells the story of the illegal strike with analysis of the unions, the state and the left, but mostly it is a tale of exuberance where workers shook off the constraints of authority and work.

It was printed at the Detroit Print Co-op and distributed through Black & Red, which still supplies bulk copies; contact them at PO Box 02374, Detroit MI 448202. Individual copies are available through FE Books.

From the introduction:

Those of us who cooperated on the publication of this pamphlet did so because the wildcat strike at the Chrysler Truck facility, June 11–14, 1974, struck a raw nerve in us.

We were excited by the collective decision of thousands of Chrysler employees to deny the authority of daily wage labor and, for even four days, to say no to the demands of the alarm clock, the production line, bosses, union bureaucrats, judges, and cops. In a society where daily activity serves so much the interests of others and so little our own, the efforts of so many to reclaim even short-run control over their lives seemed worth writing about, giving the event consideration and drawing conclusions as we saw them.

We don’t intend this publication to perpetuate the process wherein “authorities” or “experts” tell others what reality consists of; this is done daily in the media and works to keep us in the status of passive observers of our lives while the rich, the famous, and pop-stars are projected as the “important” people and the real actors of history, and the creators of events. This time it was different. Events were shaped and determined by those who usually are only spectators.

We are not a “political” group. We are not trying to “organize” anyone into a political party or “movement.” We are not trying to exhort others to greater heights of activity. We, two auto workers, a printer, a student, a teamster, a secretary, and two unemployed, want to do the same thing in our lives as the Dodge Truck strikers did in theirs: free ourselves from the tyranny of the workplace; stop being forced to sell our labor to others; stop others from having control over our lives.

But four days is no good. It only whets the appetite for what is possible. What can be done for four days can be done permanently. We want to live our lives for ourselves.

We are Millard Berry, Ralph Franklin, Alan Franklin, Cathy Kauflin, Marilyn Werbe, Richard Wieske, Peter Werbe.

From the conclusion:

What do all these varied means of resistance [used in the strike] signify? An easier way to answer that question would be to discover what they do not signify. Workers were not searching for better representation from the current authorities, management, and/or the union; nor were they searching for new leaders to become new bosses, and still go to work. They were not looking for slight improvements in working conditions.

“Everything,” offered one young exuberant worker when asked what he wanted during the peak of the strike action.

“I just don’t want to work,” moaned another during the first few depressed days of the return to work after the strike.

Horrors! How do you formulate these demands into a political program? During the strike, many people railed on about Watergate, the fuel crisis, inflation, the UAW sell-out, and the “system” in general, as well as specific grievances about the factory. The rejection of the job’s domination of our lives and the political content of the uprising were inseparable from the protest over working conditions. They did, in fact, comprise the core of the anger.

The [1973] Dodge Truck uprising and the day-to-day acts of resistance against the work process can have only one underlying cause: a generalized rebellion against forced wage-labor. The implicit realization constantly confronts us that daily activity at the work place consists of bought-and-sold labor; activity controlled by the rich and powerful for their purposes, and that much of the value created through wage labor is given to far-away stockholders rather than to the producers.

Work under capitalism will continue to distort our lives and rob us of its potential until rebellion spreads throughout the entire class of those who must sell their labor each day. The destruction of capitalist social relationships would mean the opening of a new world where work, art, creativity, and even hobbies would lose their status of separate categories and be merged into one, all at the command of each individual.

Capitalism doesn’t work for us, and each day is powerful testimony to that.

The Dodge Truck strike gave us a glimmering of what can be done. Let’s do it all.

INCIDENT:

The wildcat strike had come and gone and Chrysler was getting even with its employees for being so presumptuous as to call an end to production for four days.

On the first day of [return to] production, a brief movement to walkout at the end of eight hours failed. But later that week, the line ground to a halt at precisely 2:50 PM on the day shift—the normal quitting time for eight hours. Circuit breakers flashed open indicating something jammed in the line while short-haired, white-shirted supervisors panicked and raced to correct a very damaging situation. Idle workers laid back and laughed as maintenance men and supervisors tore open a gearbox for the line driving motor and dug out a power steering pump that belonged about 75 feet further down the line. When the same incident happened at the same time on Saturday, even management was convinced that it was not an accident, but there was little they could do but fix it and curse.

A typical executive would demand to know, “Why would these workers destroy the very means of their livelihood; it just shows what lazy, stupid, irresponsible people they are.” A union rep might say, “If something is wrong they should go through the proper channels of the grievance procedure, otherwise it destroys the authority of their elected representatives.”

Sabotage is a way of life in any large industrial operation, especially in auto plants where the moving line dominates everything. The word itself comes for the French “sabot” meaning a wooden shoe to be thrown into the machinery. That dates back to the earliest mass production.

Sabotage is not necessarily an individual act, nor is it random, nor is it really spontaneous. The methods are infinite and no corporation can protect itself from angry employees who take it upon themselves to change the conditions of their jobs. A more appropriate term might be “direct action.” It is an act of enforcing workers’ demands on the company, not an act of petitioning a mediating authority to plead their cause.