Jim Feast

The Occupation of Public Space: New York, Beijing, Oaxaca

Do squatting and occupations suggest the future for revolutionary tactics?

Robert Neuwirth, in his important book, Shadow Cities, says squatters in countries such as Turkey, Brazil, and India, are the poor, usually excluded from the adequate wage work, who do not have the wherewithal to enter the capitalist real estate market either as owners or renters.

They are “simply people who came to the city, needed a place to live that they and their families could afford, and, not being able to find it on the private market, built it for themselves on land that wasn’t theirs.” Of special note here are the numbers. “Estimates are that there are about a billion squatters in the world today [2005]--one of every six humans on the planet.” The best guesses see this group as swelling to about one in four by 2030.

The poor of the world, who are increasingly driven into metropolises by a range of economic and social conditions, can be contrasted with those in the developed world who have been called intentional squatters. They are not driven by poverty so much as by political (or other) objections to the capitalist real estate system and set up such alternative living spaces as political, artistic or women-only squats.

While political philosophies are open to different interpretations, one key element of anarchism is that ideally the poor and workers (mostly the same group) would organize their own lives using cooperative, non-competitive structures, with as little interference from the state and capital as possible. In squat cities, this is how it’s done.

A spokesman for Mumbai, India squatters (where there are over two million!) puts it like this, “We very strongly believe that the problems of the urban poor can be solved by the urban poor, not by anybody else.”

Not only do the residents build their own houses, but as Neuwirth’s survey shows, they create other more cooperative institutions. In Africa, for instance, he says, “Many women in Kibera and other shantytowns of Nairobi have developed communal self-help networks,” called merry-go-rounds. These are rotating savings clubs, out of which the women take turns drawing the purse of the combined monies. In Mumbai, another type of communal organization has been set up. “The women have created a kind of alternative dispute resolution system,” in which small disagreements are settled by this people’s court to eliminate bringing in the police, the one official institution always operating even in the worst slums.

Since the so-called “green revolution” of the 1960s and ‘70s drove so many people in the peripheral countries into urbanscapes, the existence of squatter cities has been a growing and central fact of life (see Planet of Slums by Mike Davis). Squatting has created a dual structure, recasting the way the poor in the periphery conduct their lives and perhaps offering the world a unique protest strategy. Could we not suppose that such an unprecedented historical shift in living patterns, as opposed to phenomena like the Internet or Hollywood, is conditioning the total development of the world, down to the styles of protest?

A number of protest actions over the last quarter century, from Tiananmen Square to Oaxaca, Mexico, directly or indirectly represent an attempt to transpose the squatting structure by commandeering public space for living quarters or to pursue social protest.

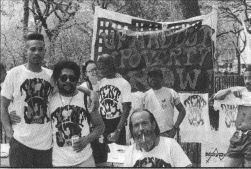

In the building of what was called Tent City in 1988 in New York City’s Tompkins Square Park, it was quite direct. The homeless needed places to live, which the city wasn’t providing. They moved into the park both to secure a place to reside and while camped out demanded the city provide housing for the poor and homeless.

One advantage to this form of protest is that, as in a newly established squatter enclave, solidarity is created among the disparate, formerly disassociated people who now congregate together.

Ron Casanova, a resident of Tent City, reminisced, “All our lives we had [passively] accepted poverty as a way of life. Now, we began doing things for ourselves.” And, Casanova brings out a second ring of solidarity. After one police raid, “The cops and Park Department had destroyed our tents, but neighborhood people brought materials for us to rebuild. We had a unity going with the neighborhood to where we had a backup of supplies.”

Neighborhood and squatter solidarity, as strong as it was, wasn’t enough to overcome a police raid which finally cleared the park in August 1988, arresting dozens and injuring at least 44 of the occupiers who resisted the assault.

In other cases, those who set up an occupation didn’t need a place to live and so they took the form of public occupation in unexpected directions. The 1989 Tiananmen Square protest didn’t set up camp in a nearby slum as the homeless did on New York’s Lower East Side (LES) as a way to avoid confrontation, but in the heart of the tourist district. While the privileged students occupying the space were from a higher social strata than those in the East Village, they received an outpouring of support from the city’s working class who took them as their representatives, demonstrated when the workers built and maintained roadblocks on Beijing’s main avenues, delaying the invasion of the Chinese army sent to suppress the revolt.

The Tompkins Square squatter camp drew aid from the neighborhood. The Beijing encampment stretched wider. In a review of Beijing Coma, I explained, “As the movement swelled, copycat groups sprang up all over the country and tens of thousands of provincial supporters poured into Beijing... There were eventually 100,000 protesters camped out in the public space.” In other words, the occupation was bringing out enormous masses to go up against the national government.

In Mexico, from May to November 2006, school teachers and their supporters set up an occupation encampment in Oaxaca City’s central plaza. Like the Chinese, the protesters had to come to grips with four central issues: demands, defense, media, and the spread of solidarity.

The demands raised by the LES Tent City and Beijing were parochial. Tent City called for homeless shelters; the Chinese students called for a dialogue with the government. In contrast, the teachers crafted demands that both spoke to their own position (more school funding) and to that of the poor villagers whose children they educated (improvements in their healthcare).

Since the Mexican government-controlled media distorted the picture of what was going on in Oaxaca, the occupiers set up a radio station in their camp and, when this installation was dismantled by right-wing thugs, as Jill Friedberg’s documentary, A Little Bit of So Much Truth chronicles, they commandeered a college radio station.

At first, the state or national governments didn’t openly interfere, but instead relied on local goon squads to attack and attempt to intimidate the protesters. Instead of relying on supporters, as the Chinese students had, the occupiers themselves set up check points in poorer neighborhoods to screen visitors as a way to keep out instigators and local government paid thugs.

As journalist Bill Weinberg makes plain, the encampment forged links not only with fellow city dwellers, but reached out into the countryside. Although eventually, the Mexican army cleared the plaza, according to Weinberg, the “APPO [the occupiers’ organization] was the real power throughout much of rural Oaxaca in the second half of 2006.”

None of these protests ended well, all being suppressed by the armed forces of the state, but their example offers a template for creation of communal mini-worlds that stress self-sufficiency and collective practice, the antithesis of capitalist and state society.

Occupations have roots in the history of protest in indigenous traditions of nations as far back as mid-17th century England’s Diggers and Levelers to recent “color revolutions” in countries of the former Soviet Union. Might it be said, though, that particular strategies are chosen at points in history because they fit in with world-dominant trends? After all, squatting has become and is a major way of living in much of the world.

Neuwirth made a powerful response to an Indian TV interviewer’s question on whether squatter communities had become “a city within the city?” His answer:

“In a city [Mumbai] that is more than 50 percent squatters, it is not the squatters who are the city within the city. Rather, the middle class and the wealthy neighborhoods constitute the small separatist enclave. The well-off are the city within the city. The squatters are the majority, so they are the city.”

Works Cited

Robert Neuwirth, Shadow Cities, London, Routledge, 2005

Ron Casanova and Sarah Ferguson pieces in Clayton Patterson, ed., Resistance: a radical social and political history of the Lower East Side (2007)

Bill Weinberg, “Oaxaca: Backward Toward Revolution,” Working USA: The Journal of Labor and Society, December 2007.

Jim Feast, Review of Ma Jian, Beijing Coma

http://www.tribes.org/web/2008/11/18/review-of-ma-jian-beijing-coma/