Chris Clancy

Class War in Chicago

a review of

The Haymarket Affair, Chicago, 1886: The “Great Anarchist” Riot and Trial by Corrine J. Naden. Moffa Press 1968

On a rainy Tuesday night in May of 1886, a rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square calling for an eight-hour workday turned suddenly violent when someone threw a bomb into the crowd of 200 policemen sent to break things up. The blast and ensuing gunfire resulted in the deaths of seven police officers and four civilians. News of the incident, known as the Haymarket Bombing, sent shockwaves around the world.

The motivation behind a children’s book publisher choosing to tackle a nearly 100-year-old incident that touches on domestic terrorism, yellow journalism, anti-immigration sentiment, multiple constitutional rights violations, and the martyring of four proud anarchists—and publish it in 1968, no less—has been lost to time. Nevertheless, it was heartening to find a children’s book about the Haymarket affair available at my local library, its pages yellowed with age, a heavily stamped checkout card in its pocket at the back.

Just the third book in 92-year-old Corrine Naden’s 38-year career of writing dozens of nonfiction titles for young readers, her Haymarket Affair Chicago, 1886: The “Great Anarchist” Riot and Trial is a remarkable artifact from an era marked by a teetering-yet-still-powerful labor movement and a public education system with barely a decade of integration under its belt. It should be noted that, one year after the book’s release, a monument to the Haymarket cops was destroyed by a bomb placed by the Weatherman group that claimed credit for the action.

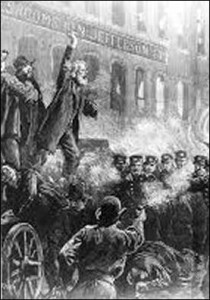

With its short sentences and numerous illustrations-mostly reproductions of wood engravings and political cartoons—The Haymarket Affair is ideal for elementary school book reports. Naden wisely begins her account by focusing on the night of the incident when the police sent to break up the workers’ meeting were met with a dynamite explosion “seemingly from nowhere.”

After this grabber, the author dives into the American labor movement of the late 19th century, providing thumbnail sketches of the rapid expansion of manufacturing in the U.S., the state-by-state installment of child labor laws, and the establishment of groups like the International Working People’s Association, with its “mainly German members” and “elements of anarchism, socialism, and communism,” as the book relates.

The author excels in describing the mood of Chicago in the spring of 1886 and the ways in which politicians, the police, the media, and the local citizenry worked together in the weeks following the riot to foment the first red scare in American history:

“The color red was left out of advertisements; foreigners in general, and Germans in particular, were damned, because many of the socialist groups were largely composed of aliens. Organized labor quickly condemned the bomb throwing, as if to get away from the scourge of criticism against labor that began to sweep the country. Some Chicago citizens planned to organize vigilante groups as a defense against the coming ‘revolution.’ The 1st Infantry Regiment was alerted.”

The pileup of details here does a good job of relating the ways in which whole communities trade away principle for vague feelings of security. But while Naden is quick to deem the ensuing trial a travesty of justice—remarking how Judge Joseph E. Gary was “highly prejudiced against the defendants”—she shies away from presenting, or even describing the views of those on trial.

It would have been nice, for instance, to read a quotation or two from Albert Parsons’ eight-hour court speech that picked the prosecution’s case apart, or Adolph Fischer’s famous assertion, shouted just seconds before he was hanged: “This is the happiest moment of my life!”

As one might expect of a children’s book, The Haymarket Affair ends on a mostly optimistic note, first with a chapter detailing Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld’s 1893 pardon of the three surviving Haymarket trial defendants, then a quick conclusion claiming that the legacy of Haymarket can be found in the eventual installment of the eight-hour workday and the Supreme Court’s revamped rulings on trial procedure.

It feels downright weird, here in 2021, to imagine how Naden might update The Haymarket Affair to account for the years since its original publication. How to account for labor unions’ role in the face of globalization and digitization? How to explain the notorious management practices at Amazon warehouses and Frito-Lay factories, or a federal minimum wage that has not risen in 12 years?

Then again, we’re talking about a year that has seen Republican lawmakers in 26 states seek to further limit public school curriculums. If impressionable young minds are deemed incapable of handling anything so controversial as slavery was bad or that women were probably not spawned from Adam’s rib, it’s difficult to think that The Haymarket Affair, however nuanced, will find a place in most schools any time soon.

Sure, I was able to find The Haymarket Affair at my local library. But I had to know what I was looking for.

Christopher Clancy is the author of the anti-war dystopian thriller We Take Care of Our Own. He lives in Nashville with his wife and daughters.