Jeff Gerth

Kent State Massacre

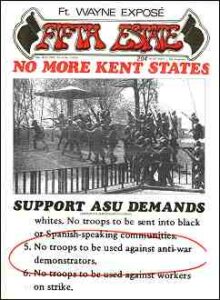

KENT, Ohio (LNS)—William Schroeder, Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandy Schcur.

Four brothers and sisters were murdered by the Ohio National Guard on the Kent State University campus May 4. At least 15 others were wounded. Three are on the critical list. Injuries to police officers were minimal.

The massacre lasted scarcely ten seconds. Three of the four died instantly. Within a few minutes the Guard had disappeared from sight. Their murder had had all the efficiency of a cold blooded killing.

Official statements to the contrary, the four days of protest started spontaneously Friday night, May 1, when some 600 students swarmed out of bars in the downtown area, trashed the windows of three banks, two credit companies, an army recruiting office and a few assorted high price stores. That afternoon there had been rallies on campus, denouncing the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, and calling for higher black admissions.

The next night, students gathered on the University Commons, defying some hastily patched together “emergency regulations,” including a curfew. Marching through the dormitories the crowd quickly swelled to about 4,000 and returned to the ROTC building adjacent to the Commons.

The building was attacked with stones and railroad flares and the 30 policemen on hand were defenseless as the building burst into flames. By the time firemen could get water on the fire (many fire hoses were severed by demonstrators) the building and its contents—including files, weapons and ammunition—were destroyed.

Sunday was relatively peaceful. Students gathered around the burnt ruins and admired their handiwork. The extension of the war had radicalized many students. One organizer commented, “Last year only 15 or 16 of us marched around that building (ROTC) at a demonstration. Last night there were 4,000 people rejoicing at its destruction.”

Following Saturday night’s blaze, Ohio Governor James Rhodes called in the National Guard. The National Guard is a form of state militia, under state control, but financed, equipped and trained by the Defense Department. About 600 troops were brought in from nearby Akron and Cleveland where they were being used against a wildcat Teamsters strike.

The Teamsters strike was settled on Sunday, allowing for the release of more National Guard to augment the original three companies of the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, and two troops of the 2nd squadron 107th Mechanized Cavalry.

The makeup of the Guard was typical, all white, from the surrounding area, with hair not too long but not too short. Most were uneasy about being there and this may account for the use of the Ohio Highway Patrol to accompany most Guard units. Many Guardsmen were simply afraid.

The mood on campus late Sunday was mixed. People were acutely aware of developments around them: the outbreak at Ohio State University in Columbus that week, the New Haven Black Panther demonstrations and the escalation of the war. On the other hand, people were wary of the massive police presence and the reduced flexibility.

There were only scattered outbursts on Sunday night, with about 60 arrests, mostly for curfew violations. People were looking ahead to the noon rally on Monday.

The gathering on Monday was an anxious one. The Commons, where the rally was held, is a large meadow fronted by the ROTC building and extending into steep-slopes on three rear sides. Monday noon found about 800 people on the Commons, with about 2000 people spread out along the nearby slopes.

There were no speeches, partially because there were no leaders, and also because in order came from the police for people to disperse shortly after they had gathered on the Commons. The demonstrators responded to the order with shouts of “On Strike, shut it down,” and “1, 2, 3, 4, We don’t want your fucking War!”

Within minutes the Guard began firing rounds of tear gas into the crowd on the Commons. This proved ineffective since the slope provided a natural retreat and protection from the gas. Realizing this, the Guard moved out from around the ROTC ruins (which served as their main base of operations) and across the Commons.

Students fled over the hill to a nearby practice football field and parking lot. There were a number of dormitories and one classroom building, Taylor Hall, nearby.

For the next 15 minutes the students and the Guard tossed tear gas at each other in the vicinity of Taylor Hall. Rock throwing was minimal. Down the hill from Taylor Hall, on the Commons, there is a large bell, usually rung for football victories.

Students used it as a clarion to announce the rally and during the course of the skirmish a few students would run broken-field through the Guard and ring the bell for a few precious seconds, a symbolic victory. Finally the Guard commandeered the bell.

A few minutes later, on the other side of Taylor Hall, a regiment of Guardsmen (approximately 15 men) opened fire on a group of about 1,000 demonstrators. Firing about 50 rounds from their .30 caliber rifles, the 15 Guardsmen gunned down over 20 sisters and brothers. Many were shot in the back as they turned to run from the Guardsmen. The rapid staccato sounded like firecrackers.

There were no warning shots and the bullets were all real—no blanks. There were bodies scattered across the lawn in front of Taylor Hall and in a parking lot between Taylor Hall and a women’s dormitory, Prentice Hall. Many shells went through cars, one passing through the windows of three cars.

The shock of the next fifteen minutes was beyond description. Without provocation and probably because they had run out of tear gas, the Guard had opened up in full view of 1,000 people. Everyone of those 1,000 were eyewitnesses to murder.

Statements from Guard officials about snipers are ridiculous.

By the time people realized what had happened, the Guard regiment had withdrawn to the ROTC area. Ambulances took forever; people were stunned, then grieving and then angry. For most, the anger came much later, and realizing this the Guard moved quickly to empty the whole campus.

A spontaneous gathering of 3,000 students and faculty was dispersed peaceably. By 2:00 people had begun to leave the city. There were no arrests, no people to bail out. Only the dead and the wounded.

The University shut down indefinitely and attempted to send students home immediately. The authorities hoped to fragment the 20,000 angry students—there are 20,000 students at Kent State and every one of them was angry—lest they begin to make that anger collective. The anger won’t go away easily. That’s why the University is closed down indefinitely.

In addition, authorities attempted to stop the outflow of any information. All phones within 30 miles were disconnected for at least 12 hours. A phone company repairman remarked “The lines are needed for police emergencies.”

Thousands more troops and highway police were brought in quickly. Kent and the nearby towns of Stow, Strongsville and Twinsburg were sealed off under martial law. School children and factory workers were sent home. The killings had been swift. The subsequent massive attempt to cover up, silence and prevent any protest was equally swift.

There are many factors which make it difficult to piece this all together. Many look to the Governor of the state, who was running for Senator in the primary election the next day. What about the Guard? Why were they so gentle on the teamsters? Were they tired from 6 days of duty? Who gave the orders? All this is unclear.

What is clear, however, is that the Kent State massacre fits the pattern of increasing repression at home. Because the U.S. is losing the war for control of Southeast Asia, it must run a tight ship at home. The war abroad and repression at home are inextricably linked—Kent State has shown that once again.

Once again, because shooting people down is nothing new to America—especially not to Black America. Two years ago on February 9, 1968 three black students at South Carolina State College, in Orangeburg, S.C. were shot and killed by state highway patrolmen during a peaceful demonstration.

The dead at Orangeburg were “shot down like dogs” said the sister of one of the victims. There was no warning, no order to disperse, no shot in the air. People began to understand then, if they hadn’t understood before, that the government has declared war on black people. The massacre at Kent State may well signal its declaration of war against young white people also.

Here at Kent State, 20,000 sons and daughters of Middle America have been thrust into the front lines.

Related

See Fifth Estate’s Vietnam Resource Page.