John Sinclair

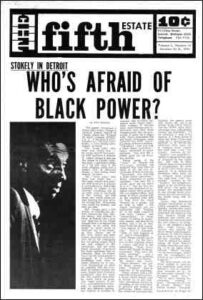

Who’s Afraid of Black Power?

Stokely in Detroit

The poster announced a mass rally at Rev. Cleage’s Central United Church of Christ, where the “friends of Snick” present STOKELY C. CARMICHAEL, Chairman, Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee.

The spelling is different now though—“Snick” (picked up from TIME magazine’s bastardization & turned back on H. Luce) brings to the ear the sound of a knife clicking open, a guillotine swipe at a fat red neck & the head plopping softly into a basket full of identical heads, a nice fitting name indeed. In/deed.

The “mass rally” this time was really that the large church was packed with brothers & sisters & sympathizers, with folks standing on tables in the balcony vestibules and up on their toes in the backs of the rooms, and with those who would settle for just hearing the man without seeing him. Everybody was ready for Stokely, and they got him.

Rev. Cleage gave a few words of introduction before announcing Atty. Milton Henry, who worked in front of Stokely like I once saw Malcolm do for Elijah (though that’s an imprecise analogy to be sure), and made as much sense as Malcolm did in his warm-up role. Henry, one of the very finest and most human attorneys in the city, took off on his colleagues for not giving proper legal aid and support to the movement, and put down black attorneys in general for their apathetic and/or cowardly (lack of) stance vis a vis the black people’s struggle. It is common knowledge that most of these lawyers try to concern themselves as little as possible with the troubles of indigent blacks and even charge their brothers exorbitant fees for legal aid that usually does them as much harm as good.

The legal system in the U.S., and especially in Detroit, is hopelessly decadent and inhuman anyway, and instead of working to correct this horrible situation most Negro attorneys manage to become even more callous and exploitative than their white counterparts, who are generally a sorry lot to begin with. Henry demanded that his black colleagues start working for their people, as they should, with the not-so-subtly veiled threat that if they don’t correct themselves they’ll be among the first to go when the real thing starts happening in the streets.

Henry spoke of the “riots” in Detroit and Chicago, pointing out (rightly) that they were no riots at all, but only indications of what is coming. “Cleveland... now that was a little better operation,” Henry remarked to great applause, “and they did a pretty good job out there in L.A. But the fact remains that hundreds of indigent blacks were jailed in the Los Angeles affair, with many of those people still in jail awaiting trial with no help from the black lawyers as a group, and no help in sight—the Negro attorneys are too concerned with “making it” in the white courts to risk their “status” and “connections” in those courts by taking an unpopular stance, and that for no money and a lot of time away from the golf course. “One lawyer in New York City,” Henry lamented, “none in New England at all, and in Philadelphia...Cecil Moore turned out to be a rat.” (At the mention of New England, heard a couple cats next to me muttering, “Yeah, what about that Brooks in Massachusetts? Why ain’t HE doing anything?” just a minor sign of the growing general awareness among the people that their “Negro leaders” are just as much crooks as the white “leaders” they’re supposed to be replacing.

Henry closed with a few remarks on the white press, a theme which Stokely was to follow up in his talk.

After denouncing the racist reporting of the movement in general and Stokely in particular, Henry warned the crowd not to believe the bullshit the papers print and, above all, not to be afraid of the FREE PRESS and the NEWS since their coverage was ridiculously biased and untruthful: “I’d be ashamed to look in the mirror if I were afraid of what the Free Press says about me.” And an “amen” from the crowd.

(In the new anti-Western tradition of the current “black power” movement, Henry curiously has involved himself in the type of program he has called for, and with 16 other Detroit lawyers has formed an organization, the name of which I don’t have, whose purpose is to defend and otherwise offer legal aid to indigent black people who need help. I say “curiously” because so few “leaders” are actually engaged in the activities they talk about—but again, the people are starting finally to see through those charlatans and are now demanding deeds along with the words.)

Henry then introduced Stokely Carmichael to his wildly receptive audience. Stokely, twenty-five years old and proud of this youth, reminded his audience that they mustn’t forget his spiritual and literal antecedents and demonstrated his own respect by bringing to the speaker’s stand Mrs. Rosa Parks, the woman who started the whole thing in Birmingham, Alabama in 1956 by refusing to move to the back of the bus. Standing ovation. Then he started his attack, taking off from Henry’s closing remarks and starting in on the white press himself. “Black”, he said, “is no mere slogan—that’s why the newspapers are afraid of our revolutionary program.”

The white press, and the white regime in general, are especially upset about Stokely’s rise to prominence because he is, as he described himself, “an arrogant black man.” “We’ve been running for centuries,” running it down, “but now we are out of breath. Stokely then quoted another “arrogant black man,” Muhammad Ali, to thunderous applause: “We got to stand up and say ‘We the greatest’ ... What we need is 22 million arrogant black people.” He went back at the newspapers again for their stupid accounts of “violence and vandalism” when they write up the insurrections in the streets of America, and reminded the people of their historical precedents: “A black man started this country by throwing a brick at the British soldiers.” The cats in front of me looked at each other, then one of them said “Crispus Attucks,” and “Yeah” from his partner, then shouting “teach us, brother!”

Stokely ran down a lot more shit and the audience got more and more into it every minute. He came down on the Negro fraternities, calling them by name, and cats who had started to cheer at the mention of their little groups were laughed down by the brothers as soon as Stokely finished his sentence. He kept pushing black. Black people have to control their own communities—that’s “black power,” plain and simple, and that’s what scares the white men in power. USE the white system, he told them—“Newark’s 54% Negro, they can all get on welfare and make a good wage.” Or take Detroit: “If you controlled Detroit you could raise the property taxes and it wouldn’t hurt us, cause we don’t have no property.” Black people have to put the white man’s game away and get their own thing together—cooperatives, stores, credit unions, Negro-owned communal property, all these things are necessary for black power. And the people cheered and cheered.

He took a few easy swipes at the white liberals, a cliche that gets triter every day, every time those folks open their mouths. “They want us to integrate—if white people believe in integration why aren’t they moving into our neighborhoods?” A good question, friends. And “I am no racist...I don’t have to tell no black man to hate white people—the white people do the job themselves every day.”

A lot of madly affirmative hollering and screaming from the audience shot Stokely even deeper into it. In a wild preaching flight of rhetoric he took off on a big part of his audience so they’d know they couldn’t just holler and scream but must commit themselves to the new order with every act. “We have to love our communities, we have to love black, we have to STOP HATING OURSELVES as what we are...It takes time to love black in this country... and it takes energy. If you don’t believe me, check the sisters with the wigs.” The braver segment of the audience (the ones whose old ladies didn’t have their wigs on) shouted YEAH. A girl in front of me (I’m in the balcony now) laughs and shouts and gives her brother some hand. She’s wearing Wranglers and a denim jacket and has her hair straightened. “It takes time and energy to love black in this country—if you don’t believe me, check the brothers who’re wearin’ a process.” More YEAHs from the college graduates. “It takes time And energy to love black in this country—if you don’t believe me, check the sisters with the hot combs!”

Then I stopped taking notes and started shouting along with everyone else. Stokely just ran it down, harder and harder. I saw Kenny Cockrel up front in the speaker’s area jumping up and down and giving hand every 30 seconds: People were flipping out all over the church, “Stokely’s so BEAUTIFUL,” and they were right. It took a young man to tell them all this, all the news they’d known all their lives, and he’d paid plenty dues to be able to be there to run it to them. They’d just let him out of jail on bond in Atlanta, where they’d charged him with “inciting a riot” among other more or less capital offenses and would have lynched him if they could’ve. He couldn’t be stopped. “We have been running so long but now we’re out of breath.... My great-grandfather took it, my grandfather took it, my father and mother took it, but it’s time for all of us now to STOP and look this thing over real good, and then do what we gotta do...BLACK POWER! BLACK POWER!” And the people came back with him: “YEAH! BLACK POWER! Tell it like it is, baby.”

But the real ending would come the next morning probably, with white America reading the latest distortions in their fascist advertising media, the newspapers, and it’s be like their favorite American couple in their favorite faggot movie, at the end of the “action,” and Martha getting that coy scared look in her eye: “Who’s afraid of black power?...George, I am.”