Bert Wirkes-Butuar (Peter Werbe)

Recycling & Liberal Reform

Problem No. 3: The Critique of Work

Problem No. 4: Affirming Consumption

Problem No. 5: Industrial Production Ignored

It was perhaps an inappropriate time to ask a question since at that very moment two climbers from Greenpeace were struggling to unfurl a banner describing the pollution which would be emitted from Detroit’s giant trash incinerator. Their problems were compounded by the fact that they were hanging in the girders of the Detroit-Windsor Ambassador Bridge some 150 feet from the water below.

I, of course, was on the ground anxiously watching the scene, but took a second to ask an equally concerned Greenpeace coordinator: If we were opposed to incineration, what then is the solution to the mountain of garbage piling up everywhere? He looked at me quickly, as if I had asked the dumbest question imaginable and said, “Recycling, what else?” and went back to the task at hand.

That was in 1987. This February, a local ecology federation, the Evergreen Alliance, held a spirited demonstration in downtown Detroit opposing proposed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations for incinerators. The almost 200 picketers expressed a range of political sentiments through street theater, chants and signs. While a majority of the posters focused on the immediate issue of the city’s trash incinerator, several others called for “Reduce, Re-Use, Revolt,” and “End Industrialism.” However, 1 was struck by the sight of two leather-jacketed young guys holding a large, printed banner stating simply, “RE-CYCLE.” Again, for them, the solution.

Reform and Revolution

The above instances bring to mind the problematic tension between reform and revolution that is always present for radicals during periods of mass social struggles. On the one hand, fighting solely for reforms has historically had the function of affirming and extending the system’s power, while on the other, waiting only for the final revolutionary conflagration can dictate an isolated existence confined to issuing angry tracts denouncing everything.

Radicals have participated fully in the great reform movements of the last 60 years—labor, civil rights, anti-war and women—but despite their best (and sometimes less than good) intentions, a disappointing pattern emerges. Periods of intense social and political upheaval are followed by the granting of formal, usually legal concessions by the institutions being confronted. This signals the reform movement’s effective dispersal as a radical challenge to power, which begins by purging the radicals involved and ends with the upper strata of the reformers being integrated into middle echelon power positions within the reformed apparatus.

This process of cooptation and dispersal occurred no matter how militantly the reforms were sought and regardless of the involvement of radicals. Defenders of these movements often argue that even in their surrender and acceptance of partial goals, they corrected wrongs, improved conditions and changed the consciousness of the culture. Although this assertion is not without some validity, a long and complicated discussion would be necessary to analyze each of the above-mentioned movements and their accomplishments. Perhaps it will suffice to say here that even after years of the union and civil rights struggles, there is no resolution to the race or labor crises and that conditions for blacks in the U.S. continue to decline sharply as does the position of working people, even organized labor.

Like the social movements before it, the environmental movement contains the potential to unravel the totality of industrial capitalism, but how can radicals involved escape the twin dangers of cooptation and isolation? At a moment when the corporate and government institutions responsible for the ecological wreckage emerge as the gleeful sponsors of Earth Day, when Vogue and Cosmopolitan ooze fashions and fetishes expressing an “ecological concern,” and when the media congratulates itself for inundating the public with environmental “information,” the cooptation appears to be 95% complete.

If this process is to be resisted, perhaps a good starting point is to re-emphasize the radical critiques of capitalism and industrialism that have appeared in these pages and elsewhere in the radical environmental movement and to keep these criticisms central to our activity. Keeping this in mind, a look at the calls for extensive recycling as a solution to many of the ecological problems we face may serve to illustrate the need to emphasize the radical over the reform.

Spoiling the Nest

Today, everyone in all sectors of the system twitters about pollution and ecology. Even the capitalists and political rulers realize by now that industrialism’s incessant assault on nature cannot continue unabated. They realize, as we do, that they are “spoiling the nest”—what they see as their nest. At present, unlike capitalism’s previous crises which have remained on economic, social or political terrains, the very legitimacy of its material basis is being challenged. The question is being posed even at the heart of the system itself: can industrialism exist harmoniously within an ecologically balanced world?

Since in the ruling circles it is taken as a given that the productive apparatus must never be significantly tampered with, recycling is posed as a universal panacea upon which all can agree and which can be realistically implemented.

Numerous municipalities across the U.S. are instituting mandatory recycling programs and more, if not all, will probably follow suit in the next few years as landfill space becomes less available and trash incineration is increasingly discredited. Many industries, seeing recycling as both a growth sector of the economy and as a public relations hedge against criticism of their products, have become big boosters of such efforts.

The former rationale is best seen in the pages of The New York Times Business Day section where articles abound like the one entitled, “Wringing Profits From Clean Air” (June 18, 1989). More recently, an article in the March 11, 1990 Times highlighting Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI), a waste disposal conglomerate, stated: “The waste disposal market is a barely tapped gold mine” and that “the nation’s second largest waste handler is adored on Wall Street.”

The public relations function is illustrated by ploys such as the recently announced McDonald’s Corporation program to recycle plastic hamburger containers and other packaging which litter neighborhoods and add measurably to the toxicity of the waste stream. Styrofoam producers and big users, such as McDonald’s, have created an industry front funded with millions of dollars called the National Polystyrene Recycling Coalition whose purpose is to blunt public criticism of plastic packaging. Even at McDonald’s most optimistic estimates, only 6.5 % of the one billion pounds of polystyrene used in all food packaging annually would be recycled in its East Coast facilities, yet it creates the image of “corporate responsibility.”

In any event, there is no real incentive for recycling all plastic restaurant waste since “virgin” styrofoam costs less than what is recycled. Insidiously, McDonald’s plans to install new “Archie McPuff” incinerators behind its restaurants, according to Everyone’s Backyard magazine.

Also, to prop up their public image, the pages of the new crop of slick ecology magazines which have recently begun publishing, such as Garbage and E: The Environmental Magazine, are littered with ads from notorious polluters (and war profiteers, in the case of GE), all extolling the virtues of recycling.

This all said, let me state what I see as the numerous problems arising from a view that recycling contains the solution to any of the environmental crises the planet faces, but end by suggesting a role it could play in a human-scale, convivial society.

Problem No. 1: Recuperation

Through the structural integration of radical demands (recuperation), the social and economic forces which generated the garbage problem in the first place intend to transform our desire to stop despoiling the earth with landfills and incinerators into an extension of their power and wealth.

Thus, volunteer efforts of concerned individuals to create local recycling programs wind up functioning as pilot projects for waste haulers seeking municipal recycling contracts. Notorious waste disposal polluters such as Waste Management, Inc. and BFI have suddenly become “concerned about the environment” when lucrative city contracts become possibilities.

Another example is the EPA’s recent directive requiring cities with incinerators to recycle 25% of their waste stream by 1992, hence making recycling a component of the mad incineration schemes environmentalists thought their efforts were undermining. Thus cities like Detroit, whose incinerator demands an enormous and continuing flow of trash, may institute meaningless, happy-face recycling programs contending this legitimizes the remainder which is burned.

A sinister, rarely considered, side to the mandatory recycling demanded by reformers is the increased power it delegates to the state and its repressive apparatus. The old anarchist adage that more laws mean more cops applies even in an arena as seemingly innocuous as garbage removal. Witness the situation in New York City where the October 19, 1989 Brooklyn Paper reports, “The persons being hired to enforce the city’s mandatory curbside recycling program—Sanitation Recycling Police Officers—will be authorized to carry guns.” This is not a gag article! The borough of Brooklyn has hired 177 armed cops to monitor its recycling program, so what starts as an effort in liberal reform, ends with more of our lives being policed by maniacs with guns.

The political state always seeks to extend its administrative control over those it rules, and now armed officials will be poking around in our garbage cans to make sure we’ve separated the green bottles from the brown ones. Any bets on how long it will take before someone gets shot by one of these cops for an “anti-recycling” offense?

Problem No. 2: A Narrow Focus

The demand for recycling creates too narrow a focus and carries with it a subtext that presents garbage disposal as the sum of the world’s problems. All calls for reforms have a tendency to do this by sectoralizing the world into an endless list of “causes” without ever confronting the totality. While some ecological reformers have no interest in changing little other than environmental quality, single issue reform efforts such as opposition to the Detroit incinerator can potentially expand the immediate into the radical.

To many participants in that fight, the giant garbage burner is perceived as being emblematic of the entirety of industrial capitalism—the insane levels of production and consumption, the arrogance and insularity of power, the class structure and racism.

Although all reform efforts have a tendency to center mostly on immediate “nuts and bolts” considerations, an insistence on viewing the totality keeps a radicality in focus.

Problem No. 3: The Critique of Work

Demands for recycling can erode the radical critique of work which places the exploitation of wage labor at the cornerstone of capital’s empire with human activity transformed into a commodity to be bought and sold. Most recycling advocates, wanting to provide “realistic” solutions (that is, ones within the current system’s acceptable parameters), assure us or even celebrate the fact that recycling will create more jobs. Some, in their enthusiasm for recycling, show a woeful lack of awareness of the role class and race play in U.S. society such as in a 1987 Detroit talk by Lois Gibbs, a Love Canal victim and Director of the Citizen’s Clearinghouse for Hazardous Waste (CCHW) which aggressively promotes recycling.

Gibbs emphasized to an attentive audience that job creation was an important part of recycling and could be presented to city officials as a selling point on that basis. She also asserted that such programs would help alleviate Detroit’s crime problem by making minimum wage jobs at recycling centers available to inner-city youth. The racial and class implications of her suggestion that blacks will benefit from a job category that cities have traditionally doled out to minorities, often at the mentioned wage, that of garbage worker, are lost in this formulation.

Gibbs’ remarks are not cited here to brand her as a racist or one who is unaware of the class nature of this society, but rather to point out that even the best-intentioned, most radical of reformers will wind up enmeshed in capital’s logic—job and business expansion—if their starting point remains within the Machine.

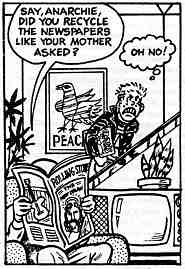

The critique of work is further eroded thusly: as noted above, recycling as an economic growth sector has developed as corporations large and small realize that profits are to be made from what was once discarded. In a society where all human labor is measured as value-producing, the individual is thrust into the recycling process by expending unpaid labor in an extended work day through “voluntary” participation as waste sorter and garbage hauler for industrial capitalism’s junk while others reap profits down the chain of exchange. We work during the day to produce commodities, and when we don’t work we are busy consuming what other wage workers have created. Now, it is proposed that our duties include the addition of cleaning bottles, stacking and tying newspapers and flattening cans for the recycling center.

Although many people express a willingness to take on the extra tasks as a contribution to a clean environment, this does not alter the nature of this activity within the political economy of capitalism. One could assume that in a post-revolutionary, post-industrial society there would be a drastic reduction in the level of junk produced and consumed with a corresponding drop in the hours spent at work. With wage work abolished as an institution and the dictates of the market and profit eliminated, people could decide communally how things are produced, distributed and discarded, free from the externally imposed needs of capital or the state. In a world which is technologically reduced and ecologically balanced, daily life’s remaining tasks may very well be more labor intensive than previously. but as in the past, what is now done only through the coercion of wages will be replaced with efforts which are cooperative in character and beneficial to the general good of the community.

Problem No. 4: Affirming Consumption

Demands for recycling can function to affirm the overall mad level of consumption itself and the item being recycled as well as obscuring what has been consumed. The only problem posed is how to dispose of what is left over—the trash—after consumption. For instance, there is joy in some quarters that 70 to 90% of the 875 million plastic bottles used annually in Michigan are made of PET or high-density polyethylene which can be recycled, and appropriate business ventures are establishing themselves for that purpose. While not questioning why so many containers are produced in the first place, this view unwittingly further legitimizes plastics production and refuses to examine critically the off-the-shelf content of the recyclable containers. Besides milk, juices and other food products (most of which deserve critical appraisal themselves), much of what comes in these jugs, tubs and jars are, in themselves toxic to the environment—solvents, cleaners, lubricants, paints, poisons, waxes, etc.

In other circumstances as well, the content of recycled items or their very existence is never questioned, such as with newspapers. Recycling daily newspapers adds injury to insult with us doing the work. Papers such as the Detroit News and Free Press are cogs in the Big Lie machine which sanctify the core myths of this society and are key propaganda organs for commodity consumption. They specifically act to distort information about events and ideas which challenge the dominance of power, so it is beyond irony to recycle a paper like the News which first editorializes that the global warming trend is beneficial and than have it reappear with support for the criminal invasion of Panama.

Another illustration is the brag of the aluminum can industry that it has recycled one trillion soft drink containers since starting such programs——with no mention of the nutritionless, sugared calories which make up the content of these cans when returned to the marketplace.

Problem No. 5: Industrial Production Ignored

The demand for recycling can overemphasize the wrong end of the problem, taking for granted the torrent of commodities spewed out by this society and concentrating only on disposing of its waste. Massive pollution takes place at the point of production and recycling can act as its ideological and even material justification if it can clean up the waste end of the process. Without a serious effort to reduce industrial production as a whole, recyclers become like jugglers who are given more and more balls to keep in the air as the productive apparatus continually seeks to expand.

There is no choice in the matter. It is the iron law of capitalism: expand or collapse. Conservative estimates by the EPA show 2.3 billion pounds of pollutants released into the air yearly through mining and manufacturing. and this figure ignores discharges into waterways and the earth which are also frighteningly high.

At any rate, there is no real political will for substantial recycling among the industrial and financial elite. As suggested above, industrial capitalism’s internal logic does not permit the latitude necessary to change its mode of production and consumption into one which considers the needs of the planet. Corporate managers have no intention of allowing complete recycling or other ecologically-based production methods to prevail since the productive and extractive industries form the core of the U.S. economy.

For instance, the largest domestic industrial growth sector is the ethylene industry which produces the basis for plastics in plants that stretch hundreds of miles, from Beaumont, Texas to Shreveport, Louisiana, along the Sabine River. These horribly polluting, dangerous plants pump out a billion pounds of ethylene annually for a plastics industry whose products quadruple each year. So important are such economic concentrations that the U.S. was willing to risk World War III in the Persian Gulf in 1988 to assure that oil was kept flowing to these facilities.

Problem No. 6: Create Another Industry

When recycling becomes a permanent feature of the economy, it will probably be utilized mainly as a technique to deal with a significant portion of urban garbage, but in itself won’t stop the destruction of the natural world. All the recycling efforts in the country can’t stop the clear-cut logging of the remaining old growth forests of the U.S. Northwest when a conglomerate which bought out a logging firm with junk bonds needs quick cash to meet its debt service.

However, recycling is not a solution even to the limited problems of waste disposal its advocates seek to correct. Extensive recycling of the Mt. Everest of trash produced daily in this country would create another mass nightmare industry to parallel what exists now, one that could conceivably cause as much pollution. For instance, the Fort Howard Paper Company of Green Bay, Wisconsin which recycles “post-consumer—waste paper is a major polluter of the Fox River and Green Bay with discharges of PCBs, dioxins, chlorinated organics, heavy metals and phosphorous into the water, plus emitting additional pollutants into the air. Its products are labeled “100% recycled.

Also, regardless of the enthusiasm of the plastics industry, a petroleum-based product is never really recycled even if it goes through a few generations and winds up as a park bench or parking strip. Eventually, it enters the environment as a toxic (having been produced in that manner) and remains there for a long time. The whole concept that plastic can be successfully recycled is more of the smoke and mirrors put forth by industry to justify continuation of unrestrained production.

However, even if none of the foregoing was a problem, one only need look at the start-up picture for a massive recycling industry to realize that it would mean more factories, more machinery, more energy, more waste, refuse and garbage, more workers going to more work on more roads in more cars, with additional suppliers, on ad infinitum. Such is the nature of capitalist expansion.

A Bleak Picture

The preceding picture may conjure up the bleak image presented earlier in this essay of the radical “issuing angry tracts denouncing everything.” However, I would hope that this angry tract joins with others to create a thrust toward the radical rejection of capitalist society—the creation of a movement that undermines the historic confidence of the ruling order and challenges its basic concepts of progress and production realizing that both threaten life, liberty and ecology. For now, our ideas and actions may only be a negation—opposition to petrochemical production, to any more growth, to wage work, to hierarchy, to the state, to the patriarchy; but from that opposition should come a material, geographically coherent community of resistance that refuses a vision that encompasses anything less than a free and green world. A future based on the limited dreams of others will become our and the world’s nightmare.

What about recycling; can it play a role in this rejectionism or is it so inherently flawed as suggested above that one should avoid it? It would seem to me, that even with the attendant problems, as the central consumer culture we have a great responsibility to try to recycle as much of the horrid mess we create as possible. However, we should do this all the while realizing that a “good citizen” approach will remain only as a gesture unless linking up with other moves against the Megamachine. In Detroit’s Cass Corridor area, a recycling project was created specifically as an adjunct to the opposition to the nearby trash incinerator. Although not free from the problems listed above and though only marginally cutting into the city’s total waste stream, recycling here takes on the form of community resistance to the incinerator’s operations—denying one’s own trash as much as possible to that which will poison you.

For some, recycling may act as a perceptual gateway to understanding the deeper problem of production and consumption in this society, but this realization should only be a small step on a journey to a world in which there is virtually no waste to recycle.