George Bradford (David Watson)

These Are Not our Troops

This Is Not Our Country

[three_fifth padding=“0 20px 0 0”]In George Orwell’s 1984, protagonist Winston Smith has acquired a copy of the arch-traitor Emmanuel Goldstein’s manual for totalitarian domination, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchic Collectivism, in which he reads that the ideal party member “should be a credulous and ignorant fanatic whose prevailing moods are fear, hatred, adulation and orgiastic triumph. In other words it is necessary that he should have the mentality appropriate to a state of war.” The novel functions in great part through ironic reversals (the subversive conspiracy is contrived by the police, etc.); it should come as no surprise, then, that the reality it illuminates is not so much the otherness of the state socialist dictatorships that it originally resembled, but rather the oligarchic collectivism of modern corporate capital and its military-industrial garrison states—those states waging their brutal crusade against “Eurasia,” now that former enemies appear to be vanquished and incorporated into the empire.

The “credulous and ignorant fanatic” now cheering on the war in highly orchestrated hate sessions—be they the nightly news variety on the telescreens, the flag-and-yellow-ribbon affairs organized by local businesses and politicos, or the half-time patriotic stage shows in the sports stadiums—is no longer Orwell’s “party member” but the loyal citizen of “democracy,” the modern “individual” member of a mob, conditioned to respond appropriately and unquestioningly. The contemporary Thought Police have done an impressive job so far, to be sure. Probably no other war in history has been more carefully packaged and controlled—not only by the state propaganda machine, but by the manipulation of the structures of meaning itself by the media in mass society. The military “spin-doctors” target the domestic population as meticulously as they chart their bombing missions. As Jean Baudrillard commented in his book America, “The Americans fight with two essential weapons: air power and information. That is, with the physical bombardment of the enemy and the electronic bombardment of the rest of the world.” (And occasionally, one notes the sanctimonious tone of concern for the enemy soldiers—as they are obliterated—in the military rhetoric of the briefing sessions. The public relations officers have picked up a few tricks from the therapeutic New Age of the 1970s.)

Even the dazzlingly blatant lie that media is undermining the war effort as it allegedly did during Vietnam—when in fact the corporate media, sharing the economic interests and outlook of the rest of the capitalist ruling class, was compliant with the military, and today functions as little more than a government cheering section—is being consciously fabricated by military propagandists and the mainstream media ideologues who serve them. This is being done for specific reasons—among them to find a scapegoat for losing the genocidal war against the Indochinese people, to keep the media on a short leash, and to condition the U.S. populace psychologically to respond with indifference when images of the actual suffering and violence inevitably slip through.

In this latter regard they have been enormously successful; witness the indignation expressed by news anchor and good citizen alike over the immorality and cynicism of a “Saddam” to seek propaganda advantages at the expense of the many civilians killed and injured—by allied armed forces. This kind of reversal and psychological projection, a function of denial, has been characteristic of the media manipulation and the response of mass society to this latest military campaign.

A Planetary Frontier

Certainly America has always been racist and xenophobic, callous to the suffering of the world’s oppressed; before this war it was already aroused by violence and fascinated with high tech means of destruction. Denial and projection were always central components of U.S. settler-state ideology. The enemies of (or those who were simply obstacles to) U.S. colonial expansion, first on this continent and then elsewhere, had to be painted as “savages” so that every imaginable brutality could be practiced upon them. It started along a frontier misnamed “New England” and continued along a frontier that by the middle of this century, in the words of Richard Drinnon, “had become planetary.” (For a detailed discussion of the process through the empire’s cultural history, see Drinnon’s Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building, 1980.)

An ideological tradition stretching back through Vietnam to the wars against the Pequots and Narragansetts was leavened with contemporary banality by Marine Brigadier General Richard Neal when he said of a downed pilot rescued inside Kuwait that he “was forty miles into Indian country. That pilot’s a happy camper now.” The connection was also understood by an Iraqi woman who screamed at a British journalist after cruise missiles had hit a residential area of Baghdad, “You think we are Red Indians, you are used to killing Red Indians.”

Today, however, imperial arrogance has more sophisticated technological means for manufacturing public consensus than ever. More importantly, it now manipulates a population that has grown up in the blue light of the mass media, a population in whom therefore the ability to think critically and to reach an understanding based on deep ethical foundations has been deformed and distorted. In his classic study Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, Jacques Ellul said of the modern citizen, “When he recites his propaganda lesson and says that he is thinking for himself, when his eyes see nothing and his mouth only produces sounds previously stenciled into his brain, when he says that he is indeed expressing his judgment—then he really demonstrates that he no longer thinks at all, ever, and that he does not exist as a person...He is nothing except what propaganda has taught him. He is merely a channel that ingests the truths of propaganda and dispenses them with the conviction that is the result of his absence as a person.”

Ellul reminds the reader that he is not referring to an exceptional case but to the norm. “Everywhere we find men who pronounce as highly personal truths what they have read in the papers only an hour before, and whose beliefs are merely the result of a powerful propaganda.” One week nobody knows of the existence of a Saddam Hussein; in a short time he has become the most dangerous man in the world, a universal bogeyman. The U.S. populace was quickly whipped into a frenzy over Hussein just as they had been over Khomeini, Khadafi and Noriega, while few people can even identify murderous U.S. henchmen like Suharto, Rios-Montt, D’Aubuisson or Sharon, and no one gets exercised over a Pinochet. (Readers uncertain of the identities of all these men prove my point that the state vaporizes any authentic historical understanding in the interests of imperial ideology.)

Television and Mass Society

But authentic history of the facts of the matter are no longer even relevant. The state does not need to control all information, along the lines of the model of a dictatorship; it is more effective, in fact, for there to be the public illusion of freedom of information as long as the terms of discourse are controlled. The entire population does not have to actively support imperial military adventures as long as the majority acquiesces in them. And as long as the majority is firmly in the grips of the propaganda machine, fragments of truth that slip through the media barrage are simply ignored because they just don’t fit into the overall picture.

Thus the obvious parallel between the U.S. invasion of Panama and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait can be widely known, along with the fact that the U.S. was Iraq’s major trading partner during the 1980s, supplying it militarily and providing huge roans while it gassed its Kurdish minority and invaded Iran. Rather, the information can be widely available, and still have no effect. People are not supporting the war because they have considered the history and the context; they are responding to the most simplified signals. As Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels wrote, “By simplifying the thoughts of the masses and reducing them to primitive patterns, propaganda was able to present the complex process of political and economic life in the simplest of terms...” Ellul comments that the massified subject no longer needs to read through the newspaper or hear the entire speech because the content is known in advance. It is not the information itself that matters but the shaping of the discourse, the model itself. The citizen “continues to obey the catchwords of propaganda, though he no longer listens to it...He no longer needs to see and read the poster; the simple splash of color is enough to awaken the desired reflexes in him.”

The hypnotic effects of television have taken this phenomenon to lengths never dreamed of by the Nazis. But the reason television works so well for the institutions of power is because it is a keystone for a whole mass society: When the masses marvel at the technological wonders of the most intense aerial bombardment in history, all the conditioned responses are being elicited and manipulated: the thrill of spectacular violence of enormous proportions, the psychic numbing in the face of real suffering that the images flatten and trivialize, the seduction of machines and speed. As Ellul has pointed out in his later work, The Technological System, one cannot simply talk about the “effects” of television, when this technology of meaning itself “exists only in terms of a technological universe and as an expression of this universe.” The entire culture deriving from industrial-capitalist organization of life conspires to brutalize human beings and condition them to become imperial automatons. They accept gargantuan, enormously destructive military campaigns because they have already been prepared by their acceptance of the entire universe of massive planning by technocratic elites in nearly all aspects of their lives. As in construction, so in destruction. The music blares, marching soldiers are shown on the screen, and all context, all history, the reality of the “enemy” as human beings all disappears. This crusade is noble simply because it is; the Nation must stand together.

The State Controls Discourse

It doesn’t matter how many dead Iraqis appear on the screens if the imperial state controls the discourse itself, and people are simply dismissed as “collateral damage” and Iraq can be blamed even for the people burned to death in busses rocketed by American planes (just what did those people think they were doing getting on those busses, after all?) or in civilian neighborhoods and air-raid shelters (they were military targets according to our technology and our “numerous sources” which are to remain unspecified for security reasons).

As media critic Norman Solomon has argued, “Denial is key to the psychological and political structures that support this war. The very magnitude of its brutality—gratuitous and unmerciful—requires heightened care to turn the meaning of events upside down. Those who massacre are the aggrieved; those being slaughtered with high-tech cruelty are depicted as subhumans, or [in a cynical phrase quoted from Time magazine] ‘civilians who should have picked a safer neighborhood.” (“Media Denies, Anesthetizes, Inverts War,” in The Guardian, 2/13/91)

The rage against the butcher of Baghdad—certainly at least as much a Frankenstein monster of the U.S. and other nation states as he is a Hitler—is probably the most ingenious manipulation of the propaganda alchemists. Every reflex of hate, fear and rage is gathered into the person of the Great Satan himself, “Saddam.” Eighteen million Iraqis magically disappear as the good citizen endorses the carpet bombing of whole regions (military targets, after all), and even calls for the use of nuclear weapons to “take out” this Saddam. (Imagine using a nuclear bomb against one man. An interesting reversal occurs in the latter idea: one lie mobilized to justify attack was that Iraq must be kept from using the nuclear weapons it was allegedly on the verge of building. Now one tactic acceptable to the discourse, whether or not it is employed, is to use nukes against the country, or at least the positions of its soldiers in Kuwait—another avatar of the “destroy-it-to-save-it” idea.)

All of the rage and feelings of powerlessness, the miseries and humiliations of living in a society dominated by powerful and mostly anonymous forces such as the state and the market economy, are channeled into a partly choreographed, partly spontaneous fury against the external enemy. Any action against the Evil Other becomes justifiable. But, predictably, the Empire eventually proves to be everything that it accuses its enemies of being. Hussein must not be rewarded for “naked aggression.” Yet in fact the U.S. not only commonly aids and abets aggression (for example when it rewarded Hussein’s bloody invasion of Iran), but is itself the world’s biggest bully and aggressor—in Panama, Grenada, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and through covert operations in Mozambique, Angola and several other countries.

Hussein must be stopped because he is bent on world domination (exactly the objective of the U.S., through its 4th Reich, the New World Order). Hussein is a dictator (a dictator, that is, who does not serve U.S. interests, in contrast with the stable of tyrants it props up on every continent). Saddam is an environmental terrorist (no mention of massive allied bombing of oil tankers, oil fields, petrochemical facilities, and so on). And—my favorite—Hussein is insane (while the Pentagon bureaucrats charting their bombing raids, of which there have been on average one per minute since the war started, are quite sane, no, even quite admirable fellows going about their jobs thoughtfully and following orders competently). Meanwhile, the vicarious sense of power derived from watching the spectral high-tech war on television joins the citizen to the state in a manner most useful to authority: mobilized passivity.

“Only Military Targets”

Another key element of manipulation has been the slow, incremental intensification of the war, a tightening of a ratchet tooth by tooth. What started out as a deployment to defend Saudi Arabia soon became the basis for attack; the war was going to be short and sweet, perhaps no more than a few bombing raids before the bad guys collapsed, then little by little the trusting citizens were told that no one had ever promised such a thing.

Along the same lines is the ever-repeated big lie that bombing targets are military targets and military targets only. (This serves a dual purpose of legitimating the massive bombardment of soldiers at the front, by the way; lying that civilians are protected enhances the rationalization that anything goes in the “theater of operations.”) But when irrefutable evidence started to slip through of massive civilian casualties, the terms were changed at the same time that civilian deaths were denied. When it became clear to anyone who might be listening closely that Basra was suffering thousands of civilian casualties and massive destruction, military spokesman General Neal replied that the city was “a military town in the true sense of the word.” As The New York Times reported, “Chemical and oil storage sites, warehouses, port installations, a naval base and other military targets, he argued, ‘are very closely interwoven with the town itself.’” (2/12/91) Thus was an entire city promoted to the status of military target.

And as the U.S. populace is hardened to the growing civilian casualties, denial and reversal are accelerated. When hundreds of people, mostly women and children, were massacred by U.S. bombs that hit an air raid shelter in Baghdad, U.S. military officials responded that the event probably did not even occur, but if it did, the Iraqi government was to blame for allowing them to take shelter in what U.S. military analysis claimed was a military center. Said one British official. “Nobody’s ever claimed we were perfect on these things.” A U.S. military spokesman responded laconically, “We’re not happy civilians got hurt, as apparently they did.” (Note how civilians were apparently hurt; getting burned alive is reduced to twisting an ankle.)

And White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater, in a stunning utterance of projection: “Saddam Hussein does not share our value in the sanctity of life. Indeed, he, time and again, has shown a willingness to sacrifice civilian lives and property that further his war aims:” (New York Times, 2/14/91) One almost forgets who is bombing whose cities. Interestingly, Fitzwater’s remark repeated almost word for word the comment of General William Westmoreland during the height of the Vietnam War. The Vietnamese did not share “our value in the sanctity of human life,” either, which was why presumably, we had to carpet bomb and napalm them, defoliate their forests and level their villages, bulldoze their cemeteries and herd them into concentration camps to achieve our own war aims. And after we have destroyed Kuwait in order to save it, leveled Iraqi cities and turned out countless dead, injured, and refugees, we can try the Hitler Saddam Hussein for war crimes, for example the roughing up and humiliation of allied pilots who, after unleashing multiple Hiroshimas on Iraq, are pictured on the front pages of the Empire’s newspapers as the victims.

And to a great degree, the populace has gone along with the signals sent over the telescreens, reflecting what can only be called the profound nazification of U.S. society. A well-dressed woman coming out of church on Ash Wednesday, the symbolic ashes of her peaceful Christ’s crucifixion on her brow, tells a reporter that civilian deaths are unfortunate, but after all, that is what happens in wartime. A refinery worker tells a newspaper reporter, “This is a war, and innocent civilians are going to be killed in war.” “My opinion stayed the same,” says a carriage driver in Philadelphia. “Accidents happen in war. You can’t avoid them.” A teacher in an affluent Detroit suburb, confronted with the irrefutable evidence of civilians burned to death in the bunker, shrugs her shoulders, saying, “I can’t believe a word that man [Saddam Hussein] says.” (In his book The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi Germany, 1933–45, Richard Gruneberger reports that when shown photographs of the death camp at Belsen by a British officer, “a German farmer commented, ‘Terrible—the things war makes happen’ as if talking of a thunderstorm which had flattened his barley.”)

Apart from a courageous, vocal anti-war minority—a legacy of what Noam Chomsky has called “the notable improvement in the moral and intellectual climate” of the country resulting from popular movements opposing imperial power and social regimentation in the 1960s (which is exactly why that decade and those movements have been so defamed by the right-wing and trivialized by the media)—the population has remained mostly passive, acquiescent, sheep-like in its obeisance and callously inhumane to the destruction. Discussing this phenomenon as far back as the late 1950s, radical sociologist C. Wright Mills wrote in The Causes of World War Three:

“In this society, between catastrophic event and everyday interests there is a vast moral gulf. How many in North America experienced, as human beings, World War II? Few rebelled, few knew public grief. It was a curiously unreal business, full of efficiency without purpose...little human complaint was focused rebelliously upon the political and moral meaning of the universal brutality. Masses sat in the movies between production shifts watching with aloofness and even visible indifference as children were ‘saturation bombed’ in the narrow cellars of European cities. Man had become an object; and insofar as those to whom he was an object felt about the spectacle at all, they felt powerless, in the grip of larger forces, with no part in those affairs that lay beyond their immediate areas of daily demand and gratification. It was a time of moral somnambulence.

“In the expanded world of mechanically vivified communication the individual becomes the spectator of everything but the human witness of nothing...The atrocities of our time are done by men as ‘functions’ of a social machinery—men possessed by an abstracted view that hides from them the human beings who are their victims and, as well, their own humanity. They are inhuman acts because they are impersonal. They are not sadistic but merely businesslike; they are not aggressive but merely efficient; they are not emotional at all but technically clean-cut...”

Patriotism, The Defeat of Authentic Community

Mills’ description of the social forces leading to nuclear world war fits the present day; in the Pentagon, technocrats calmly map out thousands of bombing raids against the adversary, while the majority of the population, numb to the suffering of the people (and the very land) in the gunsites of their heroes, cheer the battle on from the comfort of their living rooms, pro-war rallies and stadiums.

Such patriotism, though bearing uniquely modern aspects, is very similar to the war fervor nation states have always engendered: loyalty to the mythical sense of the state, the demonization of the enemy, and a sharing of the triumphalism of military prowess. In reality, however, patriotism is an expression of the defeat of community and the triumph of the state. As authentic community is progressively eroded by anonymous economic and technological forces, the innate desire for community is harnessed by the mass media to reassemble millions of atomized individuals into a pseudo-community of passion for the state and its wars. The state and its spectacle now beckon with outstretched arms to provide the only shelter from a heartless, alienated existence. Home is now the state.

Hitler anticipated this phenomenon in his description of the mass meeting, in which the individual “receives for the first time the pictures of a greater community, something that has a strengthening and encouraging effect on most people...” The individual “succumbs to the magic influence of what we call mass suggestion.” A coworker argues with a friend of mine why she supports the war: “This is something we can all believe in together.” The propagandists have learned their lessons well. In an article on the response of the population to the war, Peter Applebome writes, “War is one thing with the power to bond the nation into a unified whole,” and quotes a UCLA professor’s comment that this “moral crusade” functions “as a healing experience in relation to Vietnam.” (This man is obviously not arguing that a war can heal this nation from its mass murder and ecocidal destruction in Southeast Asia.) An Atlanta woman who makes and sells patriotic pins tells Applebome, “People want something to believe in.... They want some part of their life to have meaning” (“Sense of Pride Outweighs Fears of War,” New York Times, 2/24/91).

An America in ruins, its economy and infrastructure collapsing, its land massively contaminated, its government sullied in scandal, its foreign adventures sordid and confused, millions of its people crowded into prisons, must look to many observers today the way Weimar Germany looked to many Germans. Like the Germans, the loyalties and ideological illusions of Americans have been eroded by all the aspects of imperial decline, but they have not found any real community, values or authentic loyalties with which to replace the nationalist mystique. A crucial element of Reaganism was in fact to provide the spectacle of imperial resurgence while paying off certain privileged sectors economically to ensure their renewed loyalty. So far a large section of the populace has bought it, but for most it means little more than marching lockstep into deeper economic austerity or even combat in the service of the very institutions that have bankrupted and scattered what little community they had left.

Denial and projection are the answer: project your rage onto some “subhuman” foreign monster and deny that your own life is in ruins, that your real enemies are at home, writing out the marching orders. To achieve this state of righteous indignation, history—both recent and remote—must be vaporized. No one mentions that the bogeyman was once a former client and a stooge; no one mentions that the illustrious allies are themselves butchers. Mobs burn the bogeyman in effigy; the hundreds of thousands of people massacred by U.S. henchmen in Central America cease to exist. Even more remote history—the slaughter of native peoples, slavery, numerous invasions of Latin America, the genocide at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Korea and Vietnam—all is erased. (Like “good Germans” of fifty years ago, the citizens chuckle to a joke told over national television: “What is the similarity between Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Baghdad? Nothing, yet.” Americans, you can be a foul and vicious mob of louts.)

Vaporized, too, is the very context in which world corporate capital functions—a world in which a billion people are starving while resources are stolen from them to pay usurious loans to international banking institutions. None of the violence matters; even when it is acknowledged, the new recruits to the New World Order declare themselves simply tired of hearing about it. America is great again! Free Kuwait! Kick ass! Let’s prevent Arabs from killing Arabs by slaughtering Arabs. I am reminded of Thoreau’s comment in Walden: “They love the soil which makes their graves, but have no sympathy with the spirit which may still animate their clay. Patriotism is a maggot in their heads...” That was a century and a half ago. Now little remains but the maggot.

Support the Troops?

This is the context in which we must approach one of the most powerful propaganda messages for obedience to the imperial state, the command to “support our troops.” This has been an effective manipulation to silence people in the sway of the totalitarian-conformist culture, the line being that whatever one’s feeling before the shooting started (and a large number of war “supporters” express grave doubts when questioned), “America” must now “close ranks.” To refuse to do so is to endanger U.S. military personnel in the Middle East.

Much of the anti-war movement has responded by taking up the flag, insisting that “peace is patriotic” and that supporting the troops means bringing them home. This attitude is held even by a significant number of the families of soldiers and sailors in the Gulf, for whom the phrase “our troops” brings to mind their relatives, neighbors, friends and lovers.

Most of the troops are nothing but hostages—people recruited by a poverty draft of unemployment and racism that one black observer described as an “affirmative action in reverse.” Others joined the reserves assuming that they would be used for cleaning up after tornadoes and floods or at worst defending U.S. shores from outside attack. They are prisoners of the war machine. Among many of them and their families there is a clear understanding that they are being used as pawns to defend the interests of wealthy elites in the Middle East and the U.S. Said Maria Cotto, the sister of Marine Corporal Ismael Cotto, Jr. from the South Bronx, who was killed in early February, “I saw them on television, saying they were spending billions on this. I saw them on Wall street and they were cheering! It was sick. They were cheering like it was a game. Don’t they know it means that people will die? Not them. Not their families. Not their kids. People like my brother.”

There are plenty of troops, nevertheless, along with their families, willing and even happy to do the bidding of the Pentagon. One 23-year-old soldier told a New York Times reporter, “Every generation has its war. This is going to be a big one...I’ve been waiting for this for 18 years.” Somehow, the pacifist argument that “we want to bring our troops home unharmed” does not address the fact that some of them do not want to be brought home and that truth and freedom will likely suffer when they do. They are “our” troops and we are told to support them.

Of course, this command is linked to the lie that Americans failed to support the troops in Vietnam, that the anti-war movement mistreated returning soldiers, who were spat on and called “baby-killers.” A related article in this issue refutes this imperial falsehood in detail, but there is no doubt that soldiers must have been occasionally called baby-killers by people on their return, if not by anti-war organizers (who saw GIs as victims of the war and potential allies in ending it), then by young people revolted by the images of war that filtered home.

The fact of the matter is that a reasonable number of them had to be baby-killers, or the babies wouldn’t have been killed. Abundant evidence exists for the massacre of unarmed civilians and the commission of atrocities by American troops in Vietnam (along with their South Vietnamese and Korean allies). The recognition that the entire population was the enemy had its consequences, many of which were documented by Vietnam veterans themselves at the Winter Soldier Investigation of U.S. war crimes in Indochina held in Detroit in 1971.

The most famous massacre of unarmed civilians took place at My Lai in early 1968. One soldier who participated in another lesser known massacre in a nearby hamlet that same day said, “What we were doing was being done all over.” (See Seymour Hersch’s Coverup, 1972). Robert J. Lifton, a psychologist who along with his colleagues had interviewed some two hundred soldiers, found that none was surprised by the news of My Lai. “They had not been surprised because they have either been party to, or witness to, or have heard fairly close-hand about hundreds of thousands of similar, if smaller, incidents,” he wrote. One soldier told him, “I knew we were killing the country and its people. In any other war, what I have seen might be considered war crimes.” A wealth of such information exists in America’s libraries and in the memory of many of its people, but the latest adventures of the New World Order demand that the truth be suppressed along with common decency and humanity.

No Honor, No Glory

There is little humanity left in America today, but if any remains at all, we must be honest about these troops. They are not “our troops” but the Empire’s. They do its bidding, either enthusiastically or sullenly. As long as they simply follow orders, one cannot support them. One supports human beings, not human beings reduced to machines that acquiesce in killing not only other armed soldiers but unarmed people who die under the bombs they drop from as high as thirty thousand feet.

In his essay on civil disobedience, Thoreau comments on such people who go off to fight, even against their wills, that because of their respect for the law, “even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice.” Could such automatons be considered men at all, he wondered, or were they instead “small movable forts and magazines in the service of some unscrupulous man in power?...The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies.”

An enormous machine, made of rigid, interchangeable parts, under the direction of a central authority, acting mindlessly to bring about construction or destruction: if war is the health of the state, said Lewis Mumford in The Pentagon of Power, “it is the body and soul of the megamachine...Hence war is the ideal condition for promoting the assemblage of the megamachine, and to keep the threat of war constantly in existence is the surest way of holding the otherwise autonomous or quasi-autonomous components together as a functioning working unit.”

There is no glory in the war against Iraq; those who collude with the war machine participate in the monstrous depravity of an oppressor nation. (Let us be clear: the Iraqi nation state is also a slaughterhouse, a homicidal gang. Every nation state is, and the Baath regime is among the worst. But the U.S. global empire makes and breaks such states all the time. It is the oppressor nation among oppressor nations, which is why it will probably succeed in defeating by utterly destroying its weaker, less organized, less technologically sophisticated and poorer adversary, even if it ultimately fails to impose its will on the region and the world or destroys itself doing so.)

The “Support-Our-Troops” line has nothing to do with a concern for the well-being of the people at the front who are going to die or be wounded in this horrible, meaningless slaughter. It is a loyalty oath that helps to maintain imperial control over the discourse. The “oppose the war but honor the warriors” variant that has been adopted even by some peace activists is only a variety of the Bitburg syndrome. (Bitburg, for those who have forgotten, was a military cemetery for German Nazi storm troops where President Reagan honored the warriors of the Hitler regime.) Today the United States may be “taking out” one of the world’s most vile dictators, but America is today’s Nazi Germany, Bush its Hitler, the Marines its stormtroopers. There is no honor in following orders, either against one’s will and good judgment or willingly and fervently, particularly if the cause is ignoble. And certainly there can be no honor or glory in a colonial war and the saturation bombing of the towns and cities of a poor country.

We must support the troops in only one way, by encouraging them to revolt against the conditions of their slavery. Otherwise, they are only following orders, participating as movable forts in a military machine, the U.S. imperial army, that is a far greater threat to the long-term well-being of the world than even the homicidal creature Hussein; the sound defeat of this army, even by that lesser tyrant, would serve the slim possibility of eventual world peace. (For the Iraqis, of course, the situation is the same. The leftist call for “victory to Iraq” is perverse—it means victory to the bloodthirsty satraps who massacre Kurds, Assyrians, Kuwaitis, Iranians, dissidents and rebels. It means victory to the thugs building their own ziggurat of corpses, their own regional house of horrors, their own local empire—thugs equally vicious in their methods as the Salvadoran death squad regime and the Guatemalan generals. The Iraqi people clearly do not believe in this war—evidenced by their outbursts of joy when any slim hope of peace is held out to them. And they have no stake in it. They would do well, like their counterparts among the allied nations, to turn their guns around. Fighting for Hussein’s conquests is suicidal folly. Let both sides be defeated by the troops—let the troops unite against their officers and their respective states!)

Support the Troops: Incite Mutiny

One shudders to think what will become of the culture and politics of this country when the troops come home victorious (as they most likely will), relatively unscathed and giddy with triumph. The rulers will have a mandate for more military adventures, and other poor peoples (rarely their leaders) will pay the price in blood. Who will be next? Cuba? A mopping-up operation in Central America? All in the name of the New World Order—which is, after all, just a buzzword for the renewal of the former World Order of capitalist plunder. And the state will use the opportunity to further impose the imperial values of a highly militarized, repressive, conformist society at home.

Defeat of the Empire is preferable. If there is any justice left in this world, better that the well-armed and well-fed soldiers of the U.S. die than unarmed civilians (and draftees for that matter) of the Third World. No, these are not our troops, this is not our flag, this is not our country. The Lakota warriors who killed the soldiers and dragged away the U.S. flag from the Little Big Horn, the abolitionists freeing slaves at Harper’s Ferry, armed blacks defending themselves from the Ku Klux Klan—these are the warriors we celebrate. But such examples aren’t troops so much as human beings fighting for their lives against troops—people reduced to machines.

And whose country is this, where on cue from the telescreens, citizens scream for the annihilation of their “enemies” thousands of miles away, where they play at the war on board games while their armies smash whole cities, whole regions? This is not our country. Defeat of such a country is far more preferable, indeed, would better serve its own long-term survival as a viable human culture, than its further descent into blood-drenched elation and conquest. For its own sake as a society, America should lose this war.

Defeat does not guarantee anything, to be sure, but it slows the Empire down, and leaves a small possibility that the automata will be shaken from their somnambulence, humanized, made capable of responding once again to the suffering of the whole world. It is only a possibility, of course; defeat guarantees nothing. But otherwise, one suspects, there will be only a string of these campaigns, of Vietnams, Panamas, Nicaraguas and Iraqs, a necklace of skulls hanging from the belt of the Warrior-Father of All Wars.

Support the troops, all right—incite Mutiny. If not against this war, which may end too quickly, then against the next. For there will surely be one.

George Bradford

—Day Two of the Ground War

Related

See “The U.S. War against the Iraqi People: American sanctions are weapons of mass destruction,” FE #354, Spring, 2000.

[/three_fifth][two_fifth_last]

They are baby killers. The real figures of Iraqi civilian casualties will eventually be known, but among them are bound to be many, many children killed in bombing raids and the random strafing of roads (even shepherds tending their flocks have been strafed), but also from secondary effects like lack of clean water, food and medicine. Of the 1 to 3 million Asians killed during the Vietnam War, an enormous number were children.

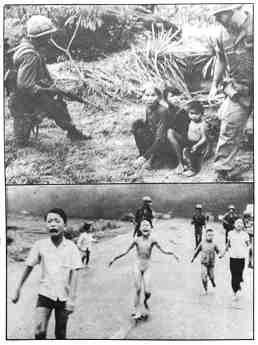

Top: U.S. “liberators” confront the enemy.

Bottom: Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of children fleeing their napalmed village in 1972. The photographer took the young girl to a hospital for her burns. Kim Phuc, now in her twenties, came to the U.S. in the late 1980s to continue treatment for her injuries. She told reporters that she bore no ill will over the war and added, “If I ever see those pilots who dropped the bombs on me...I would say to them, ‘The war is over. The past is the past.’” But unfortunately for the endless parade of victims, the slaughter never ends; only the names, faces, and places change. Kim Phuc had her reasons for speaking in terms of forgiveness. But we cannot forgive the pilots who napalmed her or the Empire that directed them. Pilots who destroy cities and villages, forests and agricultural lands; who strafe roads and carpet-bomb their enemies and never have to see them: such people are murderers. The past is the present; they are murderers still. Let their God forgive them. Let it be our purpose to do whatever we can to stop the machine they so willingly obey.

[/two_fifth_last]