Robcat

Mainers Against the Klan!

A Brief History of Maine’s Resistance to the KKK

It’s Late February in central Maine. A group of anarchists and other anti-racists have gathered at the Margaret Chase-Smith bridge in Skowhegan to respond to recent Ku Klux Klan activity around the state.

Anti-Racist Action Maine put out the call to condemn these racist terrorists. Mainers are out on the streets to let our neighbors know we will defend each other from KKK terror. This is not a plea for the authorities to protect us. Only we can protect ourselves.

In November, Klan fliers were found in Appleton. In January, more fliers appeared in Freeport, Augusta and Gardiner. They were emblazoned with a hooded Klansman flanked by burning KKKs and the group’s cross logo, and included a contact for a 24-hour Klanline: “You can sleep tonight knowing the Klan is awake.”

Calls to the hotline are answered by an automated message inviting callers to dial an extension, or visit the group’s website. It thanks the caller, and instructs them to “have a great white day.” In April, more Klan fliers appeared in Skowhegan, Waterville, and Hallowell. More demos against the Klan occurred in Freeport, Waterville, and Augusta. In each mobilization, people in the local area were the organizers, and were attended by different groups of Mainers.

In the 1920s, KKK membership exploded with an estimated high of eight million members in the U.S. When thinking about Klan activity, one tends to think of the deep South, not the North woods of Maine.

However, outside of the southern states, Maine had the largest Klan chapter in the country in the ‘20s, peaking at 50,000 members. This was the heyday of the Klan in Maine. The Klan’s first daylight march in the U.S. was in Milo, Maine, in 1923. The first Maine state convention of the Klan was held that same year in a forest outside of Waterville and attracted 15,000 people. Burning crosses were in abundance.

The Klan purchased a large estate on Forest Avenue in Portland for its headquarters, and in February 1924, 3,000 Klansmen from around the state gathered for the opening ceremony, initiating 200 new members under a burning cross. Maine KKK had daylight parades in Sanford, Gardiner, Brewer, Milo, Dexter, East Hodgdon, Kittery, and Brownville Junction. Their picnics in Portland attracted over 10,000 people.

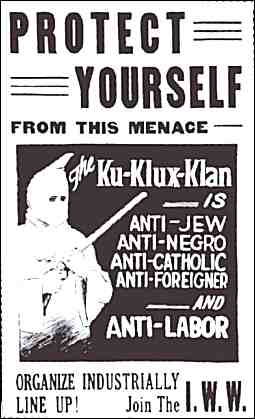

Klan popularity can be attributed to a Protestant, nativist movement directed against Franco-American, Irish, Italian, Polish, and Lithuanian Catholic immigrants. Immigrants worked in the textile and paper mills, and organized themselves into unions, including the Industrial Workers of the World.

This is where the Klan’s anti-labor stance comes from. The Klan in Maine was not only anti-immigrant, but anti-union. Jobs have never been abundant in Maine. Using scapegoats to explain capitalism’s ills is a tactic still used today. The Maine KKK of the ‘20s tapped into a long history of tense relations between Maine’s Protestant Yankee populations and Irish Catholic immigrants, who had begun arriving in the 1830s.

The chief recruiter of Maine’s Klan in the 1920s was F. Eugene Farnsworth; who went on statewide speaking tours that drew huge crowds. After the fiery hate speech, locals would be inducted into the Klan for a $10 membership fee.

Mainers also have a long history of resisting the Klan. In 1924, in Greenville, the Industrial Workers of the World went up against the Klan. The timber companies used the Klan as muscle to drive the IWW out of the area to prevent them from organizing in the lumber camps.

When the Klan told the IWW to get out of town, 175 Wobblies showed up to patrol the streets.

The first targets of the Maine Klan were Franco-Americans (immigrants from Quebec), and Irish Catholic immigrants. In Fairfield, in July 1924, Franco-Americans battled the Klan with rocks and clubs, tearing down a fiery cross.

That September, they clashed again. This time on two bridges between Saco and Biddeford. The Klan had a parade in Saco, and tried to march to Biddeford.

The Irish blocked the Bradbury bridge, and the French blocked the Main Street bridge. Both groups were heavily armed. Once the Klan saw this, they turned tail back to Saco. This action brought Irish and French immigrants together in common cause, helping them resolve their differences.

In the 1980s, the Maine Klan reared its ugly head again. They burned a cross in Bethel and held a march in South Portland, and a rally and picnic in Rumford. They were trying to capitalize on bitter feelings left by a strike at Rumford’s Boise Cascade paper mill. As before, they were met with resistance, organized by local community members, not by any vanguard group.

Over 250 anti-Klan Mainers showed up to confront them in Rumford. Some anti-racists were detained at roadblocks by the police and prevented from getting close to the rally. Blue by day, white by night! After a recruitment drive at the local high school, the Klan (including the Grand Wizard James W. Far-rands) headed to a nearby farm for a white supremacist picnic. One hundred and fifty anti-Klan Mainers also showed up. They dumped chicken shit around the picnic arena and chanted “KKK, go home!” Chicken shit for chicken shits!

Throughout Maine’s history, the KKK has been confronted at every turn, and has become progressively weaker. Now, they are afraid to come out in the open. Anarchists in Maine will continue to combat them. We will continue to live by our anarchist principles of mutual aid, direct action, and voluntary cooperation. We will continue to spread anarchist propaganda in all its forms. We will continue to talk to the potential base of the Klan’s recruiting efforts: poor and working class whites who must be educated as to who is the real enemy.

And, if the Klan crawls out of their holes and show themselves, we will do as did the Mainers of the past: attack!

Robcat homesteads and does prisoner support in Maine.