S. Flynn

Dispatch from Exarchia

“Calling all comrades!”

Athens Neighborhood is Home to Anarchy

ATHENS — In February, The National Herald, a right-wing Greek newspaper based in the U.S., boasted, “Exarchia Anarchists will be Wiped Out.” For nearly fifty years, Exarchia, a neighborhood in central Athens, Greece has been an example of autonomous living.

The neighborhood, which is the site of a number of uprisings has achieved what anarchists long believed possible; a self-organized city within a city. For decades, police who entered would be immediately attacked and pushed out.

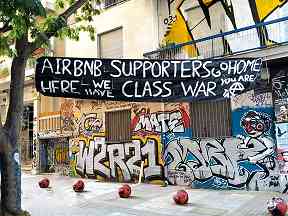

new market to redefine Exarchia. There is an Airbnb Experience

tour called “Sweet Anarchy” describing Exarchia

and its street inhabitants as if they are animals in a zoo.

–photo crimethinc. com

The neighborhood is home to a number of squats, and to radical groups such as The Ruvikanos, and the Conspiracy of Fire Cells, who have done much for the community, including housing and caring for Syrian refugees. They’ve also taken part in direct action and property destruction.

Now, a new center-right government, headed by the New Democracy Party, is putting in the greatest effort in decades to evict anarchists from their homes and community spaces in Exarchia. Prior to the election, the neighborhood benefited from the previous four years of the Syriza Party government, which was somewhat ideologically sympathetic to anarchist groups, and practiced a mostly hands off policy towards the area.

Military police have evacuated squats, sending migrants back to refugee camps. They’ve bombed music venues and movie theaters with tear gas, and for the first time in 12 years, there have been police patrols in Exarchia. The result is a battle supported by anarchist groups throughout the world.

If you are wondering where you should put your energy and support—look no further.

Exarchia comprises fifteen or twenty winding blocks, many of them pedestrian walkways, in the center of Athens. These streets surround a square—a triangle really—flanked by bookstores and restaurants, dose to the Polytechnic Institute and the National Archeological Museum. At the top of the neighborhood is Lofos Strefi—a wooded park on a hill with trails, diffs and boulders, and a basketball court.

Strefi is reached by a couple of long concrete staircases that cut through the buildings on Kalidromiou Street. To the East is Mount Lycebettus, a steep limb through wooded trails and cactuses to a tiny monastery. From the top, you can see the vast white sprawl of Athens, rolling out to the ruins and the sea beyond.

The December 2008 uprising was supported by the broader population. Violent protests swept through every neighborhood and suburb of the city, expanding out to the broader mainland and then to the islands in the surrounding Aegean Sea.

The catalyst was the murder of Alexander Grigoropoulos, a fifteen-year-old anarchist, by two policemen after a verbal confrontation between police and a group of teenagers. Grigoropoulos still lived at home in the suburbs with his parents and his death resonated with a population already beaten down by economic crisis. In the days following the boy’s murder, shops, banks and cars in the center of the city were torched. Public buildings around Syntagma Square, the seat of parliament, were set on fire.

The uprising lasted for weeks with students occupying university buildings and masked gunmen attacking police, but the heart of the protest was everyday people—women dressed for work in suits and heels lobbing broken cinder blocks through bank windows, mothers physically attacking police.

Under this intense public pressure, the cop who shot Grigoropoulos, Epaminondas Korkoneas, was sentenced to life in prison, his partner was charged as an accomplice and sentenced to ten years. The New Democracy government condemned the shooting, police issued an apology, Christmas festivities in Athens were canceled.

It’s hard for an American to imagine this kind of reaction to the murder of a child by the police. The weeks of rage were sparked by Grigoropoulos’s murder but they were borne from deep seated historical mistrust—or perhaps more accurately—a deep seated understanding of the things of which unchecked authority is capable.

On November 17, 1973, the U.S. backed military junta crushed a non-violent occupation at the Polytechnic Institute in Exarchia by driving a tank through its gates, and over the bodies of students who stood on the other side, murdering twenty-seven people. The aftermath required soldiers to squeegee pools of blood from the sidewalk into the gutters and sewers. Radio transmissions from inside the school record students appealing to soldiers as their brothers, begging them to disobey orders.

This was not an event lost to distraction or gentrification or revisionist history. The sanctuary law—which forbids police or soldiers from entering any university grew from a visceral understanding of state violence.

In the years following the massacre at the Polytechnic, anarchists were able to organize and grow the movement, and as a result built Exarchia into an example of mutual aid and solidarity, of people taking direct responsibility for their lives. People are drawn to the neighborhood from all over Europe.

The next two decades in the neighborhood saw a cultural revival, driven by the bottom up. At one point, there were ten thousand anarchists living in the neighborhood, car parks turned into gardens, a boom of public art, bookstores and publishing collectives, political meetings, lectures and actions.

What could have turned into a culture of fear after the crackdown, led to the ousting of the Junta in 1974, and solidified a culture of resistance. Exarchia is an anarchist experiment that has worked for nearly half a century. The feeling of safety, solidarity, and joy one has in the neighborhood is remarkable.

Now, the new government is threatening to eliminate the sanctuary law—a reversal that specifically targets the Polytechnic in Exarchia, a center for organizing, and for escaping police violence and surveillance.

Airbnb rentals have popped up all over the neighborhood. Investors are buying buildings hoping the government’s policy of repression will alter the neighborhood’s character enough to allow gentrification, but so far this has failed. If it is allowed to continue, it will change the fundamental character of the neighborhood which is largely made up of families who have lived here for generations, artists, writers, musicians, students, intellectuals and radicals.

Police in Exarchia have stated it’s more important to go after anarchists than to make arrests for drug use or assault. They routinely ignore destructive drug activity—something held in check by anarchists for decades.

The effort to dismantle Exarchia mirrors the prospecting that took place in Manhattan’s East Village in the 1980s, which used junkies and arson as the first wave of sanitizing the neighborhood, turning squats and artist venues into coops and housing for the rich, driving up real estate prices, and silencing political critique.

We all are needed in Exarchia. The remaining squats in the neighborhood need support to continue. The ones that have been shut down need bodies on the ground to reoccupy them.

There is a lot to learn from being here—particularly about joy and possibility. This goes beyond fighting gentrification. If there is any place we, as anarchists, can call home, it is here.

S. Flynn is a journalist living in Exarchia.