Jason Rodgers

The beasts of the Southwest desert have a message for us

a review of

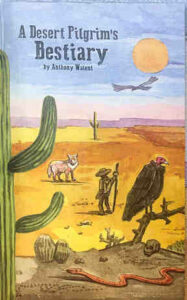

A Desert Pilgrim’s Bestiary by Anthony Walent, author; Maurice Spira, Illustrator. Eberhardt Press, 2019

A Desert Pilgrim’s Bestiary is both archaic and modern. Anthony Walent has been employing this very tension in his zine, Communicating Vessels, for many years, that is assembled and designed using functioning, but antique typesetting equipment.

Neither the zine nor this book seem retro, however. They are more like creations from outside of time. This is a good place to stand if you want to get a clear view of the crisis of modernity.

The book’s format is inspired by medieval bestiaries, characterized by naturalistic zoology, but also mythology, and usually a moral lesson. There is also an influence from later naturalist writers, such as Charles Darwin.

Using this bestiary format allows Walent to not only discuss the biological features of animals, but to use them as a springboard to discuss a multitude of other subjects. He also uses it as a chance to quote from authors ranging from Peter Kropotkin to Manly Hall, a Canadian mystic.

Using animals as a way to discuss human society can be a dangerous tactic. Some authors have fallen into some pretty goofy positions using this literary device. But, Walent seems fully aware of this danger and employs it to his advantage.

He writes “You can extrapolate virtually anything from the alleged behaviors of animals and project them onto the fabric of human society,” but “Still it is hard not to gather lessons from observing deer or bears going about their business. We will probably never free ourselves from such habits.” He uses the tension of anthropomorphism versus an amoral nature, in fact, transforming it into a dialectic. He has an interesting pragmatic take on anthropomorphism:

“I felt compelled to draw some poetic and moral conclusions based on my own reflections and research. Virtually every breakthrough in our understanding of the nonhuman animal world has involved humans entering into relationships with animals, warts and all.”

In ecology, there has been a long and ongoing feud between anthropocentrism and biocentrism. Neither perspective seems satisfactory. Anthropocentrism tends to fall into an ugly resource management model, viewing the natural world as something to capitalize, that should be preserved so that extraction can continue into the future. Biocentrism easily becomes a cold-hearted misanthropy.

This tension is subverted by the manner in which Walent considers the value of anthropomorphism as how we see the continuation of ourselves into the natural environment and our relationships with other life resonates with one’s own subjective and existential worldview.

He considers the 16th century Dutch painters Peter Brueghel and Hieronymus Bosch, particularly their use of the image of “hermetic pilgrims attempting to leave a world of mayhem.” He writes further, “you can interpret them as fitting metaphors for our own striving away from today’s manufactured Hell, a Hell that has engulfed the planet with its toxic fumes, escalating rates of species extinction, and trashed oceans.”

This is important to keep in mind. Faced with the totality, we are often left feeling powerless and hopeless. And, it can be asserted, that at this juncture, there really is very little to feel hopeful about. However, a fixation on hope misses the point.

Don’t let me mislead you; this isn’t a political book. It doesn’t include proposals for what to do. It contains stories of personal interactions with animals, poetic speculation on them, and non-ideologically related social commentary, creating an ecological consciousness that comes from the joy of being in the wild.

Walent likes to challenge assumptions about animal behavior. For instance, he talks about play in the animal world, such as black bears “running, rolling in mud, and swimming for sheer pleasure. They are obviously having a lot of fun engaging in activities that our overworked and uptight world can only dream of engaging in.”

Or, his description of cross species interaction between wolves and ravens:

“In following the wolves as they hunt, ravens ultimately gain a share of the spoils. They clean the carcass the moment the wolf pack disperses. And, mutual play happens between the two animals. Ravens peck at wolves and fly away. Then a game of tag ensues, tilted in favor of the ravens.”

Examples like this illustrate that animals are not flesh automatons governed by automatic instinct. They have a complex consciousness.

Walent does not try to sanitize or domesticate the behavior of animals. He allows them to be fierce, complex, and at times, brutal. These are not bad traits. The most amusing example is the fierceness of the hummingbird.

Walent shares a tale of a hummingbird swarming his ear, using the incident as a springboard for commenting on the creature. He observes that “the world of the hummingbird is actually furious and fierce, despite its tiny size.” Poetic language is used when he writes, “the life of the hummingbird is hidden; it is a universe with disguises. How the hummingbird fools us! Once we penetrate through the surface, a place of startling violence and spasmodic bursts of energy is revealed.”

In a way, this book is engaged in a Nietzsche-like transvaluation of consensus values. This isn’t done in a transgressive or nihilistic fashion. Instead, it portrays the beauty of nature full of fierce play. Brutality exists, but it is done without a sense of cruelty. This nature is under attack from ongoing ecocide. I came away from this book with a hope that it is possible to walk away from the monstrosity of toxic industry.

There may not be a mass movement currently to solve these problems, but if enough individuals refused and withdrew on an individual basis, there is potential for the totality to lose its power.

Jason Rodgers lives in upstate New York. Her Latest book is Invisible Generation: Rants, Polemics, and Critical Theory Against the Planetary Work Machine from Autonomedia.