Daily Barbarian

Daily Barbarian Number 8

Thoughts on the Disappearance of History (David Watson)

Thoughts on the Disappearance of History

Who What Why (Daily Barbarian)

It’s been a long time...But we’re back

Who Was Emiliano Zapata? (Daily Barbarian, George Woodcock)

by Daily Barbarian, George Woodcock

Zapatista Revolution In Mexico (Daily Barbarian, L’Unità)

Zapatista Revolution In Mexico

An Interview With Subcomandante Marcos

Related in this issue of Fifth Estate

Poetry of Abise Abousi (Abise Abousi)

Nixon Kicks Bucket (Mr. Venom)

Ding Dong The Wicked Witch Is Dead!

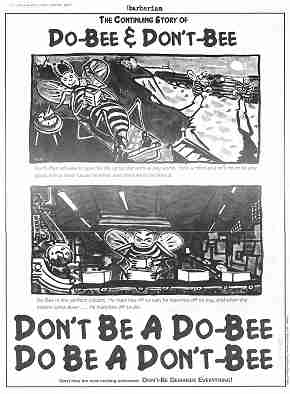

The Continuing Story of Do-Bee & Don’t-Bee (Daily Barbarian)

Thoughts on the Disappearance of History (David Watson)

Thoughts on the Disappearance of History

by David Watson

Daily Barbarian > Thoughts on the Disappearance of History

“so that when there is no more story that will be our story when there is no forest that will be our forest”

—W.S. Merwin, “One Story”

I’ve spent most of my life in the inner city of Detroit, a place both like and unlike many others in the industrialized world. I still live in the neighborhood where I did most of my growing up, attended school, met and married my wife. Despite the urban desolation, I’m tied to the place; even after long sojourns abroad, I always return to the same few square blocks.

Our house looks out on land that was gradually cleared of buildings after the 1967 black rebellion and the city’s economic decline in the 1970s. During the 1960s it had been a thriving community of poor whites and blacks, students, longhairs and young radicals. I found the local anti-war committee, a friendly poor peoples’ diner, communes, poor churches, and a sense of community there.

Like so many of the decade’s dreams, the neighborhood was demolished. At the far west end, on the other side of the expressway, was left a fascinating miniature wilderness of great, old trees, wildflowers mixed with perennials where once were gardens, and rich bird habitat. Eventually this green place was also flattened and a typically ugly housing development constructed in its place. (Named, nightmarishly, “Freedom Place,” a huge sign at the entrance lists a dozen or more prohibitions, each with the word “NO” twice the size of the rest of the lettering.)

Recently the builders returned to the section directly across from us. In a few days it was fenced, and all the trees were smashed. Expensive condominiums, almost completed, are being leased at rents well beyond the means of most locals. Our view of a park and the sunset is blocked. Someone is getting upscale, sterile housing, and someone else is getting rich, but our lives seem to be incrementally poorer.

Such things happen all the time, happen everywhere. One might wonder what they have to do with history and its abuses. I think that in a small, perhaps obscure way, our experience is like that which many people have had walking down a familiar street and realizing some landmark is missing, but not quite remembering what. It is somehow emblematic of the disappearance of memory occurring relentlessly around the globe. The process may seem anonymous because it is inertial, or because nearly everyone assumes it to be perfectly natural. But history, big and small, is not just disappearing; it is being disappeared just as surely as human beings are disappeared by dictatorships.

Of course, history has always been an ambiguous affair—a (consciously and unconsciously) constructed official story employed by powerful men to legitimate and sacralize their rule ever since the armed Mesopotamian god-kings conquered the wilderness to build their city-states. Since then, history has been a long series of cataclysms. In the 1930s, Walter Benjamin described the “angel of history” being thrown backwards by a storm out of Paradise. At the angel’s feet lies “one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.”

While he would like to “make whole what has been smashed,” the storm “irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. The storm is what we call progress.”

Despite its many disasters, there have always been counter-stories to imperial myth, and history has remained contested ground. Individual memory is a knot in the web of collective memory, and this shared history is an immense, diverse psychic commons sustaining our sense of human community, a reservoir where glimpses of freedom, and the remembrance of atrocities and triumphs are all preserved. We need this common historical space to replenish our inner capacity to remain human in the same way that forests and wild places are needed to nourish and renew the lands that sustain human communities. But just as the world’s forests are being destroyed, so too is memory’s commons.

Empires have always worked to undermine authentic memory—for example, the book burnings by the Ch’in emperors, a method still employed in our time. (This strategy was updated in 1970s China by the Maoist regime, when photographs of a lineup of party leaders were retouched to turn purged bureaucrats into shrubs.) Monumentalism is another age-old form of control. One grotesque recent case was the construction by the Balaguer government in the Dominican Republic of an enormous lighthouse, far from the sea, to honor Columbus and his “discovery”—a project which leveled poor barrios of Santo Domingo and now causes frequent electricity shortages throughout the city.

Despite their destructiveness, such methods have limited results, to which the patent shabbiness of the Columbus story and the toppling monuments of the Soviet bloc dramatically testify. There are now greater threats to memory, greater weapons in power’s arsenal. The modern transformations in consciousness brought about during the last century by mass communications and consumer society seem to be changing the form memory takes. And history’s form shapes content as surely as it takes particular words or kinds of words to make a certain kind of statement. This change evokes the legend of the Chinese emperor who decreed for himself the exclusive use of the pronoun “I.” The modern media has now donned such imperial robes, speaking while everyone else listens. One can no longer even make a revolution without making sure to seize the television stations (as was apparently the case in Romania), since instead of directly making history, people watch the screen to see what is happening. The contemporary erosion of people’s capacity to think for themselves, and the monopolization of meaning by the media, seem to be succeeding at what the legendary emperor could only have imagined.

A new society emerged in Western Europe and North America during the last century as the organic structures of life began to unravel. In the United States, where this development seems most pernicious, the colonization and control of culture was an explicit strategy for labor discipline and goods distribution. As historian Stuart Ewen writes in Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Roots of Consumer Culture, by the early twentieth century, business leaders, coming out of a period of mass labor unrest, recognized the need to manage not only production but consumption as well. A new kind of citizen had to be shaped to respond appropriately to the plethora of industrial products offered by the emergent corporate market system. Scientific time management studies in the factory were mirrored by expanding techniques of human management. One businessman wrote in the 1920s that education must teach “the masses not what to think but how to think, and thus...how to behave like human beings in the machine age.”

By the 1950s, industrial expansion and economic growth had become a universal secular religion, and consumerism an unquestioned cultural norm. Of course, the rapid obsolescence of commodities and a throwaway society was also a conscious, explicit strategy of managerial elites. One prominent marketing consultant, for example, urged “forced consumption,” arguing, “We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate.” Now that the ethos of consumerism (if not necessarily its material benefits) is quickly spreading to the countries of the post-colonial world and the former Soviet empire, the question culture critic Vance Packard asked about North American culture in the 1950s is increasingly relevant. “What is the impact on the human spirit,” he wrote, “of all these pressures to consume?”

Since then, the impact of television—which has become the key vehicle for consumer culture worldwide—has more than confirmed Packard’s fears. Television flattens, disconnects and renders experience and history incoherent. Its seemingly meaningful pastiche of images works best to sell commodities—fabricated objects devoid of any authentic history. But more importantly, it also affirms the whole universe of commodity consumption as the only life worth living. Wherever the set is turned on, local culture implodes.

Though sold as a tool that could preserve memory, television utterly fragments and colonizes it. What remains is a cult of the perpetual present, in continual, giddying motion. The jumbled, packaged events of recent and remote history come to share the relative weightlessness of soap operas and dish detergent, and perspective evaporates. Power no longer needs to shout; as Mark Crispin Miller once remarked, Big Brother isn’t watching you so much as Big Brother is you, watching. Henry Ford’s cynical quip that history is bunk comes true as people grow up more and more on television, rather than hearing about events through convivial conversation. Historical memory is now becoming what was televised, while that commons of the mind, domesticated and simulated by the media, is receding.

A striking case in point is the way people (especially North Americans) were manipulated into supporting the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Someone who has already seen tens of thousands of people “killed” on TV has a difficult time understanding the human suffering caused by the technological special effects that TV is good at presenting. Yet even the war hysteria, which one journalist described as a “nightly electronic Nuremberg Rally,” faded with time, as the images crystallized into scraps of last year’s mini-series. When Iraq was later attacked and several civilians killed on a couple of different occasions, many passive patriots who had been glued to their sets during the height of the war were now barely aware of it. It was all, as is often said, “history,”—which is to say, in the common parlance, it no longer existed. Their indifference today is as disturbing as their spasm of enthusiasm was before.

The “information society” and the culture of its mass media-driven market system are doing something to human meaning far more serious than organized government propaganda or censorship ever could. Now that the peoples of the former colonies (as well as women and other formerly invisible groups) are beginning to rediscover the stories that official history formerly suppressed, modern technique is poised to shape everyone’s story, to make them all a fragment in one long photomontage. But, to paraphrase Packard, how will so many different peoples tell their unique histories when TV itself has become the dominant mode of communication and recall? How will memory express diverse modes of being when work, buying and selling are the core of what is rapidly becoming a global monoculture? Will those cultures that aren’t as compatible with the television sensibility, and even memory of them, just disappear altogether, like the trees that once stood across from my window?

The disappearance of languages and cultures is as terrifying a prospect as the current mass extinction of species. At current rates, some ninety percent of the world’s languages will be dead or moribund in the next century. And without language, there can be no memory. Ironically, the greatest threat is to those scattered cultures whose memory precedes official history—primal and indigenous peoples, some with traditions reaching back to the Pleistocene.

The native Hawaiians, for example, have seen their culture wither under the onslaught of progress.

Today many Hawaiians speak only the language of their American conquerors, and remembrance has eroded as the places to which words and sensibilities were bound now come under the bulldozer’s blade. Enormous resorts, shopping malls and golf courses (as well as military bombing ranges) have devoured burial grounds, old fishing villages and sacred sites.

I will give just one devastating example. On the island of Hawai’i, where the active volcano Kilauea constantly creates new land, is some of the richest lowland tropical rainforest left in the island chain (only about ten percent survives). Even according to the conqueror’s laws, the forest, called Wao Kele O Puna, was to be held in perpetuity for Hawaiians to practice subsistence activities and to gather ceremonial and medicinal plants, many of which grow only there and nowhere else.

To some, the volcano is simply a resource from which geothermal energy could be tapped by harnessing volcanic steam. Though risky, it could provide energy to fuel the already obscene growth ravaging the islands. There are few meaningful memories of the place in the minds of the developers that would recommend restraint; so, in the late 1980s the state government of Hawai’i traded the 27,000-acre forest to corporate geothermal developers for some lava-covered lands where earlier drilling sites had been destroyed by the volcano.

The Hawaiians, however, have an entirely different way of seeing things; their concept of aloha aina is far more subtle, complex and fleshy than the simple translation we might give it of “love for the land.” To a Hawaiian, the terms mean not two separate elements, love on the part of a subject for an object called land (something real estate agents deal in), but rather interconnectedness and kinship, reciprocity and subjectivity, impassioned desire and an attentiveness rooted to the spirit and the specifics of place. Thus, the volcano is a living being, the goddess Pele. She created and continues to create the islands, and her family is not only the diverse life forms that slowly turn burnt land into verdant forest, but the Hawaiian people themselves.

The Hawaiians and their allies have many good reasons to fight geothermal development—its risks, its cost, its violation of native land rights, its inevitable destruction of pristine forest. (One University of Hawai’i biologist called it a place where one could see “where life comes from.”) But the project is above all an assault on the heart of their culture and religion, and thus on a tangible reminder of what it means to be Hawaiian. As Pualani Kanehele, a respected teacher of the sacred Hawaiian dance, the hula kahiko, argued, to cap Pele’s steam would be “putting a cap on the Hawaiian culture...and Hawai’i will be dead. [Then] this may as well be new California. Because we’ll all be haoles [foreigners] with the same goals as the haoles: make money.”

Meaning, like ecology, is context: everything is connected to everything else. As strands are pulled from the skein of memory, what it means to be a person within a human community shifts toward some troubling unknown. The experience of the Hawaiians, who have seen their ancestors’ bones turned up by machines where someone else’s paradise will be fabricated, lends special resonance to Benjamin’s warning that even the dead are not safe when power triumphs.

If, as Czech novelist Milan Kundera has written, “the struggle...against power is the struggle against forgetting,” the need to remember must also inevitably confront power. We may come to need truth commissions to recover shared memory, like those organized to uncover and preserve the lost stories of disappeared persons in Latin America. Taking responsibility for our past might help us uncover the complex weave of histories that now connect us all in our shared suffering and grandeur.

As I write this I imagine the new tenants across the street plugging into the free cable television they’ve been promised, staring at the instantaneous news on their dizzying array of channels, and seeing “history” in the moment it is conjured. I hear the heavy equipment beeping as the machinery backs up over the past, shifts into forward, and growls into the future.

—David Watson

Postscript: Since I wrote this essay, Pele’s eruptions have probably done more to stop geothermal development than anything else. A Supreme Court decision allowing native Hawaiians access to Wao Kele O Puna has also brought the battle to a standstill and partial victory. Many questions remain open and much destruction has already occurred. To support native Hawaiian struggles contact/donate to the Pele Defense Fund, P.O. Box 404, Volcano HI 96785.

An abridged version of this article first appeared in the September 1993 issue of The New Internationalist (1011 Bloor Street West, Toronto, Ontario M6H 1M1 Canada). The abridged version was then gutted and printed by the Utne Reader! This is the first time the above article has been printed in its entirety.

Who What Why (Daily Barbarian)

Who What Why

It’s been a long time...But we’re back

by Daily Barbarian

Daily Barbarian > Who What Why

This is the eighth issue of the Daily Barbarian and it’s been almost nine years since our last. For those of you who have been reading the Barbarian since its birth in 1979, you’re probably not surprised about the years between issues, but we haven’t been just sitting around. Since our last issue in 1986—issue number seven—we’ve put together a poetry series (Seditiously Delicionsly Oral), played music (the Layabouts) and joined with others in the Detroit area to try and stop the building of the world’s largest trash incinerator right in the center of town (Evergreen Alliance).

Recently, though, we’ve been itching to get the Barbarian back on the streets, and thanks to our friends and comrades at the Fifth Estate newspaper, we’re up and running. This issue of the Barbarian will be included as the center-fold of their latest issue, insuring that people across the country will be seeing it. This is the second time the Fifth Estate collective has helped us like this, the first time was in 1983, and we want to take this time to thank them for their unwavering support. We will also be printing an additional 3,000 copies of the Daily Barbarian to be distributed around metropolitan Detroit.

The Daily Barbarian is not named to announce the regularity of its appearance, but rather the daily activities of our modern human society and the people who keep it rolling...all of us. To us at the Barbarian, this sham we call “civilization” is just a play on words, a rhetorical trick that while posing itself as progressive and liberatory, is in reality a destroyer and slave master. It’s a bad joke that we have for all too long fallen for. Well we don’t want to wait around for the punch-line (A: world war, B: systematic starvation, C: ecological devastation, D: “things as usual”, E: all of the above) and want to bring an end to this horror, civilization, manufacturing, modern industry, modern wage-slavery, modern prisons, modern schools, modern science, modern medicine, modern warfare... We want to bring a thundering halt to all the “progressive” steps and “modernizations” that have created so much organized despair and depression, while bringing not only humans, but the entire planet to a universal code of normality and boredom, (Detroit to Damascus, Berlin to Brasilia, and all around the globe everything starts to look the same) and at worst, to the brink of complete nuclear destruction.

But we do believe there is hope. Even though we are all products of this society, we are still capable of changing ourselves and thus the society as a whole. The publishing of the Daily Barbarian is our attempt to share our ideas, hopes and desires for such a change. We want the Barbarian to be a collection of information, theory, critique, poetry, art, humor, craziness, laughter, and much, much more. We also realize that a paper cannot, by itself, change the world and it is necessary to carry on a multitude of differing activities. We will try to do this and we hope you will too!

Who Was Emiliano Zapata? (Daily Barbarian, George Woodcock)

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

by Daily Barbarian, George Woodcock

Daily Barbarian >Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Emiliano Zapata was born in 1879 in Morales, Mexico.

In 1911, when popular demands for land reform were dismissed by Mexico’s then dictator Porfioro Diaz, Zapata and the indigenous peoples of Morales began fighting a guerrilla war that lasted almost ten years. By 1914, with an army of 30,000 Zapatistas, Zapata, along with Pancho Villa’s army, occupied Mexico City

Unlike Villa, Zapata never compromised his principles or those of the Zapatistas. Because he was incorruptible, Zapata was assassinated in 1919 by Colonel Jesus Guajardo, of Venustiano Carranza’s army. Nevertheless, the revolution of the indigenous peoples of Mexico has continued as Zapatista groups, like the present day EZLN, have continued to appear across the entire country.

Below is an excerpt from George Woodcock’s book Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements.

...Emiliano Zapata, whose activities in southern Mexico during the revolutionary era resemble remarkably those of Makhno in the Ukraine, for like Makhno he was a poor peasant who showed a remarkable power to inspire the oppressed farmers of southern Mexico and to lead them brilliantly in guerilla warfare. The historian Henry Branford Parkes remarked that the Zapatista army of the South was never an army in the ordinary sense, for its soldiers “spent their time plowing and reaping their newly won lands and took up arms only to repel invasion; they were an insurgent people.” The philosophy of the Zapatista movement, with its egalitarianism and its desire to re-create a natural peasant order, with its insistence that the people must take the land themselves and govern themselves in the village communities, with its distrust of politics and its contempt for personal gain, resembled very closely the rural anarchism which had arisen under similar circumstances in Andalusia. Undoubtedly some of the libertarian ideas that inspired the trade unions in the cities and turned great Mexican painters like Rivera and Dr. Atl, into temporary anarchists, found their way to Zapata in the South, but his movement seems to have gained its anarchic quality most of all from a dynamic combination of the leveling desires of the peasants and his own ruthless idealism. For Zapata was the one leader who never compromised, who never allowed himself to be corrupted by money or power, and who died as he lived, a poor and almost illiterate man fighting for justice to be done to men like himself.

Zapatista Revolution In Mexico (Daily Barbarian, L’Unità)

Zapatista Revolution In Mexico

An Interview With Subcomandante Marcos

Daily Barbarian >Zapatista Revolution In Mexico

San Cristobal, Mexico: Subcomandante Marcos is one of the few guerrillas in San Cristobal who has his face covered and is armed with a machine gun. As he speaks, he takes a pipe from his watch pocket, places it in his mouth through the opening in his mask, but doesn’t light it. He expresses himself with the clarity of an intellectual used to communicating with less educated people. He is clearly Mexican, but it is impossible to place his accent. A young woman with Asiatic eyes in a black ski mask stands next to him throughout the interview.

L’Unità: Commandante Marcos, you took San Cristobal on January 1st. But who are you people?

Marcos: We form part of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation(EZLN), and we demand the resignation of the federal government and the formation of a new transition government to convene free and democratic elections in August 1994. We demand that the principal demands of the peasants of Chiapas be resolved: Food, health, education, autonomy, and peace. The Indigenous people have always lived in a state of war because war has been waged against them, while now it will be for both Indians and whites. In any case, we have the opportunity to die fighting and not die of dysentery, which is how the Indians of Chiapas normally die.

L’Unità: Are you part of some peasant political organization?

Marcos: We have no relation with any type of above-ground organization. Our organization is exclusively clandestine and armed.

L’Unità: It was born from nothing; that is, improvised?

Marcos: We are not an improvised movement; we have been preparing in the mountains for ten years. We have matured, thought, learned, and we have arrived at this decision.

L’Unità: Is there racial and ethnic content in your demands?

Marcos: The Directing Committee is formed of Indigenous Tzotziles, Tzeltales, Choles, Tojolabales, Mames, and Zoques, the principal ethnic groups of Chiapas. All of them are in agreement, and apart from democracy and representation, they demand respect, respect which white people have never given them. Especially in San Cristobal, the “coletos” [citizens of San Cristobal] are very insulting and discriminatory with respect to the Indians in daily life.

Now white people respect the Indians, because they see them with guns in their hands.

L’Unità: What do you think the government’s reaction will be now?

Marcos: We don’t worry ourselves about the response of the government, but about the response of the people, of the Mexicans. We want to know what this event will provoke, what will move the national consciousness. We hope that something will move, not only in the form of armed struggle, but in all forms of struggle. We hope it will bring an end to this disguised dictatorship.

L’Unità: You don’t have confidence in the PRD [Democratic Revolutionary Party headed by Cuahtemoc Cardenas, mildly leftist, may have actually won the presidency in 1988] as an opposition party in the next elections?

Marcos: We have no confidence in either the political parties or in the electoral system. The government of Salinas de Gortari is an illegitimate government, the product of fraud, and this illegitimate government will necessarily produce illegitimate elections. We want a transitional government and that this government hold new elections, but with a capacity that is genuinely egalitarian, offering equal conditions to all the political parties. In Chiapas, 15,000 Indians die every year of treatable diseases. It is a number similar to that produced by the war in El Salvador. If a peasant with cholera arrives at a hospital in the rural areas, they carry him outside so that no one says there is cholera in Chiapas. In this movement, the Indians that form part of the Zapatista army want in the first place to dialog with their own people. They are their true interlocutors.

L’Unità: Pardon me, but you aren’t Indian.

Marcos: You have to understand that our movement is not Chiapaneco, it is national. There are people such as myself who come from other states, and there are Chiapanecos who fight in other states. We are Mexicans, this unites us, as well as the demand for liberty and democracy. We want to choose our real representatives.

L’Unità: But now, don’t you fear heavy repression?

Marcos: For Indoamericans, the repression has existed for 500 years. Maybe you’re thinking of the type of repression practiced by the south American governments. But for the Indians, this kind of repression is an everyday thing. Ask those who live in the surrounding communities of San Cristobal.

L’Unità: What development would you consider a success?

Marcos: We would like others in all parts of the country to join this movement.

L’Unità: An armed movement?

Marcos: No. We make a broad appeal that we direct towards those who participate in civil, legal, and open movements.

L’Unità: Why did you choose January 1st and San Cristobal?

Marcos: It was the Directing Committee that decided. It is clear that the date is related to NAFTA, which for the Indians is a death sentence. The taking of effect of the treaty represents the beginning of an international massacre.

L’Unità: What do you think of the international reaction? Aren’t you afraid that the United States could intervene as it has done in other parts of Latin America?

Marcos: The United States used to have the Soviet Union as a pretext, they feared Soviet infiltration in our countries. But what can they make of a movement that claims social justice? They can’t continue to think that we are being manipulated from the outside, or that we are financed by the gold of Moscow, seeing that Moscow no longer exists. Enough with asking Yeltsin. The people of the U.S. should be aware that we struggle for that which everybody wants, that the European countries have wanted. Did not the people of Germany and Italy rebel against dictatorship? Isn’t it equally valid that the Mexican people rebel? The people of the U.S. have a lot to do with the reality that you can observe here, with the conditions of misery for the Indians and the great hunger for justice. In Mexico, the entire social system is founded on injustice in its relations with the Indians. The worst that can happen to a human being is to be an Indian, with his burden of humiliation, hunger, and misery....

...There is not in the movement of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation an ideology perfectly defined, in the sense of being communist or Marxist-Leninist. There is a common point of connection with the great national problems, which coincide always, for one or the other sector, in a lack of liberty and democracy.

In this case, this sector has used up any other method of struggle such as the legal struggle, the popular struggle, the economic projects, the struggle for Sedesol, and it ends following the only method which remains, the armed struggle. But we are open to other tendencies and to other forms of struggle, in the enthusiasm to generate a genuine national and revolutionary movement that reconciles these two fundamental demands, liberty and democracy. On these grounds a movement can be formed that will breathe a genuine solution to the social problems of each sector, whether Indigenous or peasant, worker, teacher, intellectual, small business owner, of the small and medium-sized industry.

The repression of the Indigenous population has been present for many years. The Indigenous people of Chiapas suffer 15,000 deaths per year which no one mourns. The great shame is that they die of curable diseases and this is denied by the Department of Health.

We expect a favorable reaction from Mexican society towards the reasons that gave birth to this movement, because they are just.

This interview was taken from the newspaper Love And Rage vol. 5, no. 1 (Box 853, Stuyvesant Station, N.Y., N.Y. 10009) and the magazine Covert Action Quarterly no. 48 (1500 Massachusetts Ave. NW #732, Washington, D.C. 20005).

Web archive note: comments in brackets appeared in the print original.

Related in this issue of Fifth Estate

“Insurgent Mexico! Redefining Revolution & Progress for the 21st Century,” FE #344, Summer, 1994

“Who Was Emiliano Zapata?” Daily Barbarian supplement, FE #344, Summer, 1994

Poetry of Abise Abousi (Abise Abousi)

Poetry of Abise Abousi

Daily Barbarian > Poetry of Abise Abousi

veruschka

I am thinking about myself now. I have been photographed a thousand times. It was always the same in the blue dress, red satin or black silk with gloves to my elbows.

And I had always known you and you had always known me, even when we didn’t. Is that the way it seems? You wanted it different for me, saw me not on a horse or walking down stairs with a drink in my hand, but naked and everywhere painted into something—a barn door, a room packed with burlap and cotton cloth and me in the midst, you had to look twice to see. And how did it begin, in the bed with my head painted into the pillow, my body the exact shade of the sheets. My favorite was in the forest, sitting at a table, everything green, overgrown with moss, but my shape was still there, still my own. I would just walk right into it, wherever you saw me next, and you would do the rest, camouflaging until I almost disappeared.

I told you when I’m sick it is something else. My head hurting is really a door closing down the hall or a car accident in the street below. My heart beating fast is a bird landing on the window sill.

Do you know that when you pack tumbleweeds into boxes when you take them out they will have become square? How would you expect them to move now and where would they fit but neatly under things?

I am in the bath but there is no water, just my body, because it is what I want to be right now, cool and white. I have found the right color of paint and am only waiting for you to return to make me completely this.

After two hours you arrive holding in your arms wood you have collected from along the shore. You drop the bundle in the center of the floor. If you start a fire right here the dilemma becomes how will I fade into it? Painted the color of fire or fire itself. Either way my eyes will be open and dancing. You will make me out in this way and if you look closely.

* * * * *

that day

He thought he sealed

his daughter in an

envelope years ago.

He is the Minister

of Information for

one of the smallest

countries in the

world but he cannot

remember her name or

guess at her whereabouts.

The address on the envelope

has long since become

a blur in his mind

full of other details.

Although on that day

there were two public

hangings in the square

and six pieces of fruit

in the bowl on the table

(two pomegranates, a mango

and three figs) and the

soft sound of a woman

sweeping in the hall

outside his door. Or

maybe the day coincided

with the opening of

a display of new street

maps at the museum and

the woman on the balcony

across from his own

hanging her clothes

to dry in the dark

hours of morning

(two white shirts, two

light blue, four pairs

of black socks and

one grey dishdasha.)

Either way, he knows

the day he ran his tongue

quickly across

the seal then pressed

the envelope closed

before walking out

into the street in

his brown laceless shoes

on a day that the bugs

were not so bad and

a taxi honked for him but

he preferred to walk

the eight or twelve

blocks and drop the

letter in the box.

That action coincided

with the last time

he saw his daughter

that much is clear

and now he sits

his back always

to the door each day

as the mail arrives.

One or two envelopes

slide almost soundlessly

into the dust

just inside his door.

* * * * *

a different place

and so it has come to this

and so this has come to it

a man and woman standing

alongside the road

it has been wanting to rain

for days the clouds all

gathered in the corner

of his falling eye

he can not remark

her heart he has noticed

is beating in her hair

and ears he feels it

buries his face in it

leans against the car

that is not there.

.

they are here to wait out the storm of her hands

which have been dripping at her sides for days

(a man, a woman, and a stray)

.

the man has hidden one shoe from the dog

he wears the other one on his right hand

to show the dog he has command

on the guard wall across from her is painted

“I heart Lisa Fletcher” in blue

she has stared at the words

on and off all day

she thinks to herself now

take me to a different place.

.

every other car has its hazards on

and her hands continue to madden the man

he has become all wrapped up in her

beating heart hair as night comes

he thinks she will begin to attract fireflies

mosquitoes to her face and damp hands

all cars going north move a little then stop

a truck driver has left all that behind

to join the man and woman alongside the road

.

and at any other time he might make a fierce friend

but tonight he is tanked and cannot take his eyes

from the woman’s hands he will continue to

comment incessantly at the way they pour forth

he says take me to the same place.

.

the dog has appeared

he has found the shoe

he is on the grassy incline

licking it gently all over.

.

will her hands stop when the rain starts

the engine of the fastest car

that passes before the man sees

his good eye in her opposing eye

and she has moved now to the overpass

above the road to hold her hands over it

take me home to a different place

the same she says as the clothes

that hang on my neighbor’s line

restrictions to dry clean only once

the truck driver is scratching himself all over

he wants to run her hands through the wringer

she thinks she has

been everywhere now

but to a different place. —

.

this night she is violently ill in the sudden rain

with the cars going by they turn their

lights dim and dimmer still

they have all seen her at least once

in the same place she’s at now and

can familiarize themselves without

slowing down to stop but to recognize

herself she must close her eyes.

.

the truck driver has left the dog

asleep at the wheel to confront the man

he tells him it is her hair

that should concern us now

the way it seems to drag.

.

she has always thought the same

what could change but the way we

sit stand cough walk

and she can take more if you see her

in this light from a different place

is she there she wants to be

where there is no trouble or

at the home of her mother

who will tell her some of this

is that different place and

some of it is not to be taken seriously

you must wash up.

.

, she has friends in cars that know her

she cries from behind her book

when they don’t stop

she thinks little about her hands now

the man says that she is inconsiderate

to no longer appreciate the green and

white striped soap he brings to her

from various restrooms along the road.

.

she can bring to mind sinister

and seamstress at one time

she says something about the sound of cars

on the wet streets below used to

make me jump from bed now something

from in me I know makes these rain drop hands

and the music they make takes me to a different place

so don’t wait up but the man had long since gone

the way of the truck driver and dog

with nothing on his mind now

but freeways and places to stop.

About These Pages:

Both Alise Alousi and Michael Mikolowski are two artists that are deeply involved in the cultural scene as well as being active in local and international social movements.

In future issues of the Daily Barbarian, the center pages will carry the work of local artists, along with reviews of recently published books and journals.

Nixon Kicks Bucket (Mr. Venom)

Nixon Kicks Bucket

Ding Dong The Wicked Witch Is Dead!

by Mr. Venom

Daily Barbarian > Nixon Kicks Bucket

The day after Richard Milhouse Nixon died, I noticed while driving to work that the flag at the McDonald’s on Woodward Avenue was hanging limply at half-mast.

Richard Satanic Millhouse Nixon, Richard Slaughterhouse Nixon, Richard Whorehouse Nixon, Richard Deathhouse Nixon. Tricky Dick Nixon, arguably the most despised U.S. politician in the 20th century. At long last, we wouldn’t “have Nixon to kick around” anymore. I was getting sick of hating him, anyway. Good riddance to bad rubbish.

Then came all the repulsive eulogies and flim-flam about a Nixon of Shakespearean proportions, a man of “enormous vision” brought down by “tragic blindness.” This “tragic Nixon” legend is an insult to the intelligence. Nixon should have been remembered as “the man in the glass booth,” after being hung for his administration’s gruesome war crimes in Indochina, Chile and elsewhere, Instead, he died in his bed, forgiven by the official media for what were only his petty offenses at Watergate. Patriots, apparently having taken a wrong turn on their way to Graceland, placed flowers at the doors of Millstone’s presidential library.

Also that nauseating funeral, with Henry Kissinger sermonizing to a roomful of bigwigs and politicians—where are those Islamic Jihad militants with their truckloads of dynamite when we really need them? As for politicians, they never change. According to one of the members of the current camarilla (a career liar who once worked for Nixon), today’s resident of the White House “loved the lucidity of Nixon’s mind.” That’s some kind of weird, bad joke—like the ludicrous babbling of one fairly typical pundit who noted the “remarkable persistence and towering size” of that slouched, paranoid, vicious, self-serving, conniving and mass-murdering wretch. “For an American who came of age with him in the second half of the twentieth century,” blathered Frank Rich in The New York Times, “making peace with Richard Nixon proved in the end an essential part of growing up.”

Sorry if we disagree. Some people—particularly those paid by the rulers to manufacture the consent of the governed—might think “growing up” means surrendering one’s principles to make peace with one of the most contemptible villains of the century. We’d rather stand with his myriad victims. It just isn’t possible to make peace with the architects of genocide and maintain one’s integrity and honor. Coming of age with Richard Nixon (whose “statesmanship” the Cuban newspaper Granma once appropriately elucidated by turning the x in his name into a swastika) meant witnessing the obliteration of whole countries to appease the craven ego and save the job of a vile warped fraud. It was a daily pageant of mendacity, corruption, and bureaucratic brutality. True, it may not have been fundamentally different from political power at any time, but it had a particularly sordid character to it all that is difficult to describe to those too young, or too accommodated to power, to remember

The evil inanity that foreign policy was “Nixon’s forte” is especially repellent. If Nixon was shrewd enough to “open China” (allegedly his greatest achievement), it was only because the maoist dictatorship had been begging for western business for years. Coming of age with Nixon meant seeing the images of him and Mao toasting one another at the very moment U.S. B-52 bombers were punishing the Vietnamese people with some of the heaviest bombing runs of the war.

To be sure, Nixon was a tragic example of what Wilhelm Reich called the mass psychology of authoritarian society—resentful of his “betters,” contemptuous of his “lessers”, distorted even physically by his suspicion, rancor, venality, and hypocritical machinations; and perfectly willing to defame or destroy anyone who might impede his rise to power. But contrary to the fairy tales, there was no other side to him, no idealism, no grand vision, none of it. Nixon rode the pervasive baseness, foolishness and fear of American society to its summit. until his corruption sent him into an early (and comfortable) retirement. But he never paid for his real crimes, and their tragic consequences were not borne by him but by his victims.

The squalid meanness, ignorance and inhumanity he exemplified are still with us, which explains in part the nostalgic outpourings and flowers. It will probably take world-shaking transformations to bury once and for all whatever it is that causes a Richard Nixon to occur. Let us lay flowers at the threshold of that possibility.

The Continuing Story of Do-Bee & Don’t-Bee (Daily Barbarian)

The Continuing Story of Do-Bee & Don’t-Bee

Daily Barbarian back page graphic

Daily Barbarian > The Continuing Story...

Full-page two-panel cartoon

Top panel shows a bee relaxing on a chaise longue and two other bees looking at the relaxing one.

Caption says: Don’t-Bee refuses to give his life up to the work-a-day world. He’s a rebel and he’ll never be any good, he’s a rebel ‘cause he never ever does what he should.

Bottom panel shows a bee working on an assembly line.

Caption says: Do-Bee is the perfect citizen. He marches off to war, he marches off to buy, and when the orders come down... he marches off to die.

Below panels:

Don’t be a Do-Bee

Do be a Don’t-Bee

Don’t miss the next exciting adventure: Don’t-Bee demands everything!

Poster: Larry Talbot and Stephen Goodfellow (Detroit 1994)