Alon K. Raab

Mother Earth

Emma Goldman’s anarchist magazine

a review of

Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth, Edited with Commentary by Peter Glassgold, Counterpoint, 2001, 428 pages, $25.

“A spectacle, the terrible events of today strengthen this conviction, that war is permanently fostered by the present social system. Armed conflict is the natural consequence and the inevitable and fatal outcome of a society that is founded on the exploitation of the workers...To all the soldiers of all countries who believe they are fighting for justice and liberty, we have to declare that their heroism and their valor will but serve to perpetuate hatred, tyranny, and misery.”

These words were written during a time of crisis. The enemy has attacked. The U.S. government has declared a crusade, vowing to protect civilization. A wave of jingoism and patriotism, fanned by the mainstream media, has spread across the land.

Labor is called upon to sacrifice, and anything but total support of the President is pronounced treason. The government uses the cover of “national security” to implement its long held plans of suppressing basic rights of speech and organization.

Dissenting voices are heard and the authorities respond by raiding offices of radical groups and publications, charging activists with aiding the enemy and jailing hundreds of them. The year 2001? Very possibly, except that the words were written in 1917 and are part of Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth, edited by Peter Glassgold.

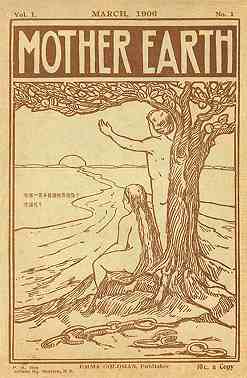

This timely new collection presents early 20th century anarchist activists and writers in their own words and actions and makes connections to the events of today. In March 1906, Mother Earth, a 64-page magazine measuring 5x8 inches and costing 10 cents, burst upon the scene.

It was a time of rapid social and political change, with movements for women’s and workers’ rights, civil liberties, educational reform, and modernism in the arts gaining momentum. For the next 12 years the journal was at the forefront of many of these currents.

Its publisher, Emma Goldman, known as “Red Emma” for her politics, was a seasoned organizer and writer. She chose the name Mother Earth in honor of “the nourisher of man—man freed and unhindered in his access to the free earth.” The cover featured a naked Adam and Eve under a tree, their broken chains cast away, facing the rising sun.

At the time, Goldman was a nurse and operated a “Vienna scalp and facial massage parlor,” but the warm reception to the magazine enabled her to change careers. Although Alexander Berkman and later Max Baginski served as editors and the egalitarian ideals of the group aimed at a non-hierarchical structure, it was Goldman’s charismatic personality and money raising lecture tours that made her the dynamo that powered the venture.

Always operating on a shoestring, its offices were in Goldman’s various Lower East Side apartments, the longest being at 210 East 13th St. As with the best of journals, Mother Earth was also a center of political and cultural activity as a pamphlet publisher, a bookstore (at 4 Jones Street in Greenwich Village) and a social “scene” with wild masquerade parties named “the Red Revel balls” where hundreds of radicals came in costume (Goldman appeared as a nun) and danced “The Anarchist Slide Waltz.”

The group’s political activities continued until government repression in the form of censorship, raids, arrests, trials and deportations, ended the journal’s life in 1918. The rise of industrial capitalism helped to relegate this attempt at social change to an obscure place in the history books. And yet, one hundred years later, reading Goldman, Berkman and their comrades, one is amazed by how current they are.

The publication announced itself as “devoted to Social Science and Literature,” and quickly earned a reputation as a gadfly, unafraid of championing unpopular causes and aiming sharp arrows at the pillars of the current order. A broad range of topics were examined, and were always contextualized as part of a larger framework of anarchist social revolution. Anarchism was defined by the journal as, “the philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man made law...a condition of society regulated by voluntary agreement.”

“This book was born of curiosity and need,” writes Peter Glassgold in his introduction. Until now, only a few articles were available. Glassgold, a translator and editor of Latin and Dutch poetry and the author of The Angel Max (a novel set in the Jewish Anarchist milieu of the early 1900s) faced the daunting task of choosing among 5,000 pages of material.

He decided on short, well-written pieces which appeared in the magazine and “had to be both relevant historically and representative of the magazine while speaking as well to the issues of our day.” In this he succeeded very well, as throughout the book one discovers that the same issues with which these early radicals struggled, from a woman’s right to her own body to militarism and government curtailment of free speech, are still with us today.

The anthology is divided into six sections: Anarchism, The Woman Question, Literature, Civil Liberties, The Social War, War and Peace. There are lively articles about the role of art in furthering social change, the attempts of workers to unionize, and the dangers posed by state and Mammon. Among the events described are the 1913 Ludlow, Colorado massacre (where families of striking miners were murdered by John D. Rockefeller’s hired guns) and the trial of IWW union activist Frank Tennenbaum whose crime was leading the unemployed into churches demanding food and shelter.

The contributors are a diverse group, with significant works by women and immigrant writers. Stories and poems of Louise Bryant, Eugene O’Neill, Tolstoy, Ben Hecht and Margaret Anderson, and cover drawings by Robert Minor and Man Ray, along with passionate essays by Goldman, Kropotkin, Voltairine De Cleyre and leading leftist firebrands make for a thought provoking collection.

Reading the Mother Earth anthology with the perspective of a century affords insight. The group’s strong faith in “the great moment when the earth will become a home for all” caused them to see the nationalist impulse so prevalent then as about to be swept away by the forces of brotherhood. The many ethnic wars of the last century, the religious and national hatreds (from Kosovo and Kashmir to Israel and Rwanda) make one pause, although today’s activists will also be able to find many signs of growing global solidarity.

In his illuminating introduction and notes, the editor does not hesitate to criticize the magazine for its lack of humor, adherence to conservative literary and artistic forms, and failure to nurture new talents. Glassgold also does not ignore the personal shortcomings of the activists and writers, their squabbles and interpersonal dramas that accompany every group of idealists seeking to change the world, only to face again and again their own limitations.

But as Glassgold notes, what distinguished this magazine and circle was the willingness to challenge conventional wisdom and reject much that they found odious while also proposing alternatives, and trying to live them.