David Watson

For Pat ‘the Rat’ Halley

“The layman Ho asked Basho: ‘What is it that transcends everything in the universe?’ (another version: ‘If all things return to the one, to what does the one return?’)

“Basho answered: ‘I will tell you after you have drunk up all the waters of the West River in one gulp.’

“Ho said: ‘I have already drunk up all the waters of the West River in one gulp.’

“Basho replied: ‘Then I have already answered your question.”’

Our old friend Pat “the Rat” Halley was a man who could drink up all the waters of the West River in one gulp.

He was elemental, had a fierce and happy, but dark spirit. He was passionate and impulsive and intuitive. He had a violent temper, but he was mostly gentle. He came from a place and context that is not supposed to produce artists or visionaries—a rough and tumble, working-class Detroit background. But Detroit is also known to produce such people, both in spite of what it is and because of what it is. Pat’s raw, idiosyncratic, chaotic creativity produced a kind vital, madcap “wild wisdom” in storefront theaters, parks, and on the street—the kind of things for which Detroit has become Famous.

* * *

“The roaring of lions, the howling of wolves, the raging of the stormy sea, and the destructive sword are portions of eternity too great for the eye of man,” wrote Blake. It was clear to those who knew him that there was no small portion of these things in Pat.

Blake was of course also announcing the arrival of Romanticism. We were living in some late stage of the Age of Romanticism in the 1970s, full of the spirit of Blake, and of the rebels and dandies, the dadas and surrealists, the situationists and the modern rebels who considered themselves realistic in demanding the impossible. Pat was a part of that heyday, gave it spark and color. His intuitive celebrations of madness and defense of so-called mad people, his faith in the virtues of childhood and the creative energy of children, his primitivism and respect for primitive and tribal peoples, his celebration of nature and wild animals, his resistance against regimentation and domestication, his comedic craziness containing a spiritual sense of the unity of life in all its energy and asymmetry—these were all romantic sensibilities. He had not gotten them from books—though, like Whitman he’d read more books than he let on in those days. But these impulses were natural to him. He was one of the most natural anarchists I ever knew. He was pure lightning.

In fact, I first met Pat in the midst of a thunderstorm, amid great claps of thunder and flashes of light. The first time I saw him he was up in a cottonwood tree, in a field in Macomb County behind some new housing at the frontier where the city was grinding up farm and forest. He was laughing and howling at the storm, a young Zarathustra Lakota heyoka shaman, the way a nineteenth century poet might tie himself to a tree by the sea shore to witness the power of a hurricane.

* * *

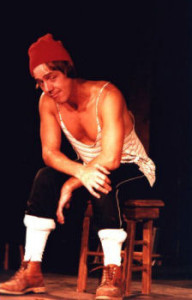

All of Pat’s adventures seemed to push at frontiers, and against a civilization that was working inexorably to turn men, women, and children into machines. He resisted enclosure and challenged laws, written and unwritten. Wherever freedom made its claims, Pat was near, or at the center of the action. He wrote for the Fifth Estate, published books of poetry, and worked in several theater troupes, organizing a rough, spontaneous, proletarian theater of cruelty in the Primitive Lust Theater and the Freezer Theater, in the vernacular and spirit of down-and-dirty Detroit. At his plays, usually leavened with wrestling matches, one could typically see a Saturday-night slam-down between the Devil or the Marquis de Sade and an unusually large and hairy nun.

As Diane Polish, another friend, remembered, Pat wrote most of the plays, “but other talented people contributed plays and skits. Probably the most famous production was a satire on the Jonestown mass suicide (when Jim Jones, and followers of his religion committed suicide—or were forced to kill themselves—by drinking poisoned Kool-Aid) At the end of the performance, we offered Kool-Aid to the audience, but few availed themselves of the free refreshment. Another great piece was the one in which Pat led the audience through the alleys of the Corridor, with actors popping out from behind trees and trash bins.”

* * *

No wonder he chose as his totem animal the rat—a resilient, resourceful mammal living by its wits in the cracks of civilization, a clever outsider vilified for being what the bourgeois civilization that fears it is—a plague. In a more ceremonial, ecstatic culture like that of the American Indians, whom he admired, he would have been a sacred clown, simultaneously opening fissures in daily life to the mysteries, and challenging and laughing at the mysteries, too—keeping the balance in imbalance. He was so much in the two worlds, or the many worlds.

As Dirty Dog the Clown, he chose another pariah animal to mock the hypocrisies and injustices of the modern world. He seemed to be following the path of the pre-Socratic philosopher Diogenes, who as a slave was far freer than his masters, and who had mocked the civilization around him as vanity, once declaring, “They treated me like a dog, so I pissed on them.”

We would go to those performances, watching him sing and bark and croak and pronounce, cooking up some sly commentary—“In case of nuclear war,” he once advised, “make sure to take the stairs”—while blowing madly on his harmonica, as his goofy harangues bubbled forth, sometimes falling flat but not infrequently exploding into an implausible utterance of genius. And we would ask ourselves, as we shivered in the cold air of the unheated Freezer Theater in the winter or broiled there in the summer, how did he pull that off?

* * *

He made fun of his friends, too, of course. Sylvia Inwood told us that once she was at the headquarters of the White Panther Party while some addled naifs were sitting, passing the Red Book of Chairman Mao around and reading from it. Pat got into the circle and, taking the book and pretending to read, started making up completely ludicrous quotations, such as “Women are sheep-like and must be treated as sheep....” as the cadres nodded approvingly, if less than comprehendingly.

I can even now hear his voice, saying, “Man, ain’t that a load a shit.” Good rat that he was, he could bullshit, too—especially if he was dealing with a cop or a boss. But Pat was no bullshitter. He practiced a kind of lunacy in the tradition of the old taoist and zen masters, taking risks for the sake of insight, or to carry out a gesture of freedom and human affirmation, or for the sake of his friends. But he was real—too real for his own good, perhaps—and he had a goodness in him that, combined with his sense of daring and playfulness, could be a danger to him.

In 1973 a pudgy rich kid calling himself the Guru Maharaji was touring the country pretending to be a god and “Lord of the Universe” and promising to deliver world peace—for the price of one’s obedience and one’s money. He had sucked in his share of hippies and even former radicals. When they learned that he was going to be given the key to the City of Detroit, Pat and other friends met at the Bronx Bar across from the FE offices to plot an attack. After the presentation at the City Council chambers, Pat approached wearing an imbecilic grin and bearing a pizza box covered with flowers recovered from a funeral home, and let him have it with a shaving cream pie. It was planned well and it made the newspapers and then the national media.

Divine laughter-1; Divine imposture-0.

Pat later said he “had always wanted to hit God in the face with a pie.” But in that act he was actually defending the numinous and the possibility of divinity, which—like his precursor Whitman, who also contained multitudes—he never separated from the reality and beauty of our animal body, from nature and our human nature, and from the simplest and most authentic acts of human liberty. He knew instinctively that we were not meant to be slaves, either to God or Master, and that some divinity deeper than divinity resides in us all. In fact, down deep, Pat had a deeply spiritual sense of the miraculous. His untamed, audacious disregard for pomp, for sanctimony, for authority, for the desire to accumulate wealth—none of this was ever cynical in the modern sense of the word. There was always an affirmation in it, of life and of love.

In a statement he wrote at the time, he stated, “This should not be seen merely as a protest against this Guru, whom I consider a fraud, but also as a protest against 2,500 years of illegitimate religious authority.” Years later, in an Internet forum with former members of the cult, Pat wrote that local followers of the guru had told him “that the word was I was going to be a single-celled organism in my next life. My response? ‘Beats the hell out of a radioactive isotope.’”

He had a blast mocking those who would exploit this reality and attempt to subvert and replace it with submission and slavery. It wasn’t his idea alone to pie the flimflam god as he made his way from City Hall to his Rolls Royce limousine. But it took courage and a reckless sense of selflessness, and yes, of divine play, to be the one to do it. And in doing so he became an early practitioner of what was soon to become a widespread, and admirable (and indeed, non-violent) anarchist form of propaganda of the deed—the bringing down of hated political and cultural figures with a well-placed pie.

* * *

Pat paid for this playful gesture, too, and nearly with his life—in part because he was at some moments so ingenuous, and so willing to see the best in people, when he should have been suspicious. Thus, not long after, he let himself be taken in by two of the guru’s operatives claiming to have broken away from the cult, and they attacked him with a hammer and left him for dead. He survived, but many of his friends wondered if that attack didn’t change him.

“The last time I saw him was when I called and insisted he come to my home after he had been beaten,” wrote Dee Vickers to us. “I wanted to make sure he was really okay. He came over and we had an afternoon-long talk. He refused a lift home and the last I saw him, he was walking down the street. His zest for life seemed different after the beating. But his ability to show you different ways to look at life and his humor had not changed.”

This judgment seems right. Life was hard on Pat, but he still had that spark. He moved away from the FE, occasionally giving us an article or sending a letter. He was too much of an individual even to work with a bunch of anarchists.

Pat met Linda Zimmerman in the Fifth Estate office, and they eventually married and had a son, Jesse. The marriage did not last, but Linda and Pat had finally become friends for the sake of their son and their grandchildren, and she praised him at his memorial as a true and good and generous friend. As Linda reminded us, people often found that if they admired something of Pat’s he was suddenly forcing them to take it, and loading it into their car.

* * *

Pat was impulsive, and passionate, and there was a roughness to his dharma bum beatitude like that situationist text with the sandpaper covers. He was destined to push and grind against the confines of his covers, and those of others. As another old friend, Lowell Boileau, put it, “Pat was the classic round peg in a square peg world.” He could be a very good friend, and husband, and father, and comrade, but he could also be hard on the people around him, the people he loved and who loved him. Passion and asperity commingled in him.

Ultimately, living in this world took its toll on Pat. He lived on the margin, making his living driving a cab, because he could maintain his sense of self there, and it gave him time to think, and to write. (In 1994, he published a story on his experiences in The Detroit Metro Times, titled “Wild Rides.”) But the margin was also hard on him—this is a familiar Cass Corridor story, a Detroit story. A society based so much on meaningless work, on the unquestioning obedience to illegitimate authority, on the accumulation of money and power, and on a disrespect for the natural world does not treat its visionaries well, and this society eventually did Pat in. He was too proud, I guess, to ask us for the help he needed, and perhaps we could not have given him what he needed. Some men can only take so much beating down.

In the end he was suicided by society, to borrow Antonin Artaud’s expression about Van Gogh—suicided by all the pressures with which this world can burden a man—the tribulations and death of his son, and legal problems and money problems brought about by accusations as absurd as they were vile, and including the prevarications of a rotten cop. That’s another Detroit story, and a Macomb County story, if there ever was one. Only a revolution could right this wrong. And so some of us will continue to value the possibility, however remote, that will turn this world back on its feet as it should be, with its head in the stars, so the whole world can know who this man really was.

* * *

Pat should have lived running barefoot, dropping bison on the prairie with a flint knife a thousand years before the white men arrived. But after years of being beaten down, this working class mystic and visionary cabbie was still unbowed, proud of what he had managed to do and what he had managed to survive, able to laugh at himself and at life, however sadly, even standing by the coffin of his own son, possibly the greatest blow imaginable to any man or woman.

He was a poet, a mystic, a revolutionary, a comrade, a friend. His friends know who he was, and love him, and will remember him. He was a man who could and did drink up the whole of life in a single gulp. I drink to his memory now.

—David Watson, November 2007

For more on Pat Halley, search this site; also see

http://www.corridortribe.com/obits/pat_halley/pat_halley.htm