David Widgington

Islands of Resistance

a review of

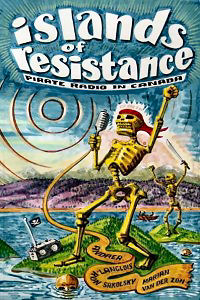

Islands of Resistance: Pirate Radio in Canada by Andrea Langlois, Ron Sakolsky and Marian van der Zon. New Star Books, 2010

After reading Islands of Resistance: Pirate Radio in Canada, all I wanted to do was become a pirate. Not the kind that steals in a capitalist bent to become rich at the expense of others. I want to appropriate what is already mine: the public airways and broadcast what corporate media despise most--defiant free-form radio that encourages audio creativity and promotes social justice.

The 246-page anthology, edited by Andrea Langlois, Ron Sakolsky and Marian van der Zon, is a collection of 16 essays and a docudrama in seven acts that explain why pirate radio is important in a digital age, with examples of where it practices across Canada

Topics here on resisting regulation, radio and anarchy, indigenous voices, protest tactics, temporary autonomous radio, radio art, gender politics and more are all discussed in detail throughout the book with a defiant flare; I was moved to use my favorite open-source torrent software to find myself a copy of the 2009 film, Pirate Radio, a feature-length fiction about an offshore pirate radio station, based on such dissenting luminaries as Radio Caroline, Radio Luxembourg, Radio Atlanta and many others.

The editors chose to embrace the term ‘pirate’ even though its pejorative ring may associate it with theft and mayhem or with swashbuckling Hollywood imagery. As stipulated in their introduction, they like it because it inspires “both the radical imagination and the practice of direct action.” But not all the contributors seem to agree. Neskie Manuel’s modest contribution to the book with Secwepeme Radio didn’t need an abundance of words to express the role of their broadcasts, which are not necessarily pirate in nature as he so eloquently outlined: “Our position is that as aboriginal people we did not give up our right to make use of the electromagnetic spectrum to carry out our traditions, language and culture...It is the modern version of the campfire where people would share stories.” He continues later in his essay with what may be the most radical and empowering statement of the entire book, “We are not pirates, we are Secwepeme.”

Broadcasters don’t need to be on a ship to be pirates. They can broadcast their voices from the forest as they do in Barrier Lake, “one of the poorest native communities in Canada.” This indigenous community is located just five hours northwest of Montreal and is today “perhaps the southernmost example of a traditional, sub-Arctic hunting society in Canada” where the youth still speak the Algonquin language. Traditions and their native language are threatened by the lack of schools on the reserve, forcing kids to towns like Val-D’or and Maniwaki more than 150 kilometers away.

The ‘Voice of the Forest’ broadcasts are listened to by community youth as well as the elders. One anecdote that emphasizes community in the radio project describes an elder woman that drives up to the radio station to tell the DJ, “No more Rap! Put on some country--we want to dance!” A lot of people, including elders, were at someone’s house listening to the radio. The DJ responded by putting on a large selection of country tunes, set the playlist on repeat with some premixed station IDs mixed in, locked the door to the station and headed out to a friend’s where a slice of the community were also listening to the same music. Developing a listenership is not easy, but in Barrier Lake, the community was listening.

Setting up radio broadcasting capabilities like they did in Barrier Lake will have long term benefits for the community but pirate radio is also useful for the short term as a protest tactic. The chapter, Amplifying Resistance, discusses the role of low-watt broadcasting during protests to offer protesters information about the meanderings of a snake march, the movement of police, and of arrests. Another important use is the possibility of using the broadcasts to inform the adjacent community of the protest’s underlying issues. By promoting the location on the FM dial to residents along a protest route, they can be encouraged to tune in and listen to a live broadcast.

I remember Free Radio Tent City that authors Andrea Langlois and Gretchen King write about. It was a low-watt broadcast during the July 3, 2003 occupation of a Montreal park to protest the lack of affordable housing during a housing crisis that found hundreds of people homeless. Protesters were encouraged to bring their own radios to the protest and tune into 104.9 on the FM dial. The broadcast unified the squatters by tuning all in to a collective voice where listeners were encouraged to join the conversation.

These few examples give a glimpse of how pirate radio is being used and practiced across Canada. The book’s editors note that pirate radio projects are not necessarily easy to document by the ‘illegal’ nature of their broadcasts and their efforts to remain clandestine. Others did not wish to be referred to in the book for fear of government reprisal. I am glad Islands of Resistance is filled with gaps of information about the pirate radio mediascape because it’s nice to know that there are still pirates out there whose furtive efforts have kept wind in their sails.

David Widgington is a media activist and mobile journalist based in Montreal. His blog is at