David Watson

Remembering Federico Arcos

See also: [[http://www.fifthestate.org/archive/395-winter-2016-50<sup>th</sup>-anniversary/remembering-federico-arcos/other-remembrances/][Other remembrances of Federico Arcos]] (online only)

Introduction

Federico Arcos (July 18, 1920-May 23, 2015), a lifelong anarchist, participated in the Spanish Revolution and Civil War in the 1930s, and later took part in the antifascist underground there. He immigrated to Canada in 1952, where he continued his commitment to anarchist goals. He eventually compiled an extensive archive of anarchist writings and other material.

Fifth Estaters met Federico in the early 1970s. In time he became a beloved elder to people working on the paper, and in the larger Detroit/Windsor anarchist, radical, and labor communities. The 50th anniversary retrospective exhibit of the FE at Detroit’s Museum of Contemporary Art is dedicated to Federico. It runs from September 2015 to January 2016.

The following remembrance is presented with the understanding that each generation of rebels confronts the leviathan of oppression and exploitation in its own way, using the ideas and resources passed on to it by those who came before. Today’s anarchists and anti-authoritarians fight for a future free from hierarchy and exploitation, developing means and strategies as they go. For some, living memory of the struggle goes back to the Occupy movement, for others, Seattle in 1999. Those of us who became active in the 1960s and ‘70s were personally acquainted with veterans of the revolts earlier in the century, from whom we drew deep inspiration and courage. Because the fight for freedom is still ongoing, awareness of the lives and legacies of yesterday’s fighters and battles remains relevant, in fact essential.

—Robby Barnes

Remembering Federico Arcos

We have gathered here today to remember and to celebrate our dear friend Federico Arcos—Fede, as many of his friends knew him. Yesterday, July 18, was his ninety-fifth birthday. It was also the anniversary of the military putsch in Spain in July 1936 that sparked the response of the poor and working classes of Barcelona, and other parts of Spain, which became the Spanish Revolution.

For many years a community of friends, comrades, and admirers of Federico gathered around this time of year to wish him well, to toast and roast him, and to affirm the anarchist and humanist ideals he espoused. So, here we are, gathered once more to celebrate and honor him, to celebrate and honor the ideals of freedom, solidarity, and love. And so, a toast to Fede, nuestro amigo, hermano, compañero, padre, abuelo, y yayo. If you don’t have anything to drink, raise your arms in the old anarchist salute, with a clenched fist and the other hand clasping the wrist, a gesture he often made from his porch, tears in his eyes, when we drove away from his house. ¡Viva! [TOAST]

When some of us on this side of the river met Federico back in the early-mid 1970s, he really did not drink at all, or almost not at all. He was very serious, and a little puritanical in the style of many of the old anarchists, eschewing cigarettes, alcohol, and earthy language. He could be pretty judgmental about such matters. But over the years he loosened up, and would take a small glass of wine for the toast. He also became looser and earthier in his language when we spoke, and funnier.

Federico was a dedicated comrade; he disapproved of so-called Latin time, and usually arrived early to work on projects or to visit friends. He never suggested putting something off that could be accomplished immediately. But he was funny, and fun-loving, and sometimes erudite. He always, as long as we knew him, regaled us with a profusion of proverbs, expressions, tongue-twisters in Spanish and Catalan, poems, and jokes (some a little more ribald as time went on). He believed in the power of the word, and he would recite reams of poems from memory—some of it nineteenth century, over-baked romanticism, true, but wonderful to hear from him. He spoke French, Italian, Catalan, Spanish, English and serviceable Portuguese, and at one time could “defend himself” in Arabic, as they put it in Spanish. He was moved to tears by great music, poetry, art, and by stories of human courage, altruism, and suffering—and by his memories.

He usually became very emotional reciting poems and reflecting on his life. This was not simply a question of old age, though it did become more pronounced over time. His old friend and fellow Quijote del Ideal, Diego Camacho, once told me that Federico was “always a bit of a crybaby, a llorón,” a well-known romántico who cried easily, even as a young man, when moved by life’s pain or its beauty.

In such moments, remembering his fallen friends, Federico would insist that everything meaningful to him—who he was and had become, his adherence to his principles, his hope in the future—he owed to them. And he would add that he also owed it us, his community, his compañeros now. He meant the radical and anarchist community here, but also he meant the people in the union and on projects with whom he collaborated in Windsor.

To us, Federico seemed to have washed up on the shores of this Strait from some terrible shipwreck, the destruction of a world and vision that briefly flourished and might have still been, but for the evil men do. But his energy, his hope, and his memories of that dream had an effect on all who came to know him. In his biography of Emma Goldman, Rebel in Paradise, our friend Richard Drinnon quoted Goldman’s often repeated observation, “If you do not feel a thing, you will never guess its meaning.” Federico’s deep feeling connected him, and helped to connect us, and he came to embody in his humble way almost everything that really mattered to us as well.

Before you start to think that I am immortalizing him, let me say that Federico was a humble man, simple in some ways but also complicated. He was imperfect. Like all of us, he had his moments of vanity and of ire. He was proud of his contributions, and could be vain about them as he got older. He could be petulant with friends and others about differences of opinion, and he was at times a tyrannical father when his daughter did not follow in his footsteps to fight for el Ideal.

But usually the vanity came from an understandable pride in largely if not entirely having resisted the bribery of modern society and its array of commodities and consumption, and in having contributed to the struggle for human freedom in ways that he would remind you were modest. He always insisted that he was “not good enough” to be a revolutionary or an anarchist because, as he expressed it once in “Letter to a Friend,” an essay published in the Fifth Estate, for one to claim such a designation, “it would be necessary to reach the extreme point of sacrifice and to devote oneself without reservation to doing good, without limit and without cease.”

One may be tempted to see this as more romanticismo, but in fact he fought in a revolution and saw it defeated, and the inevitable human suffering and despair that followed, and he lived with the fact, never forgot the fact, that several of his closest friends and compañeros in the revolution and later the anti-Franco underground died in the war and its aftermath. He remembered José Gosalves, a young Quijote who died of illness in the internment camp in France. And José Sabaté and Francisco Martínez, killed by Franco’s cops. And José Pons and José Pérez Pedrero, captured and executed in Franco’s prisons. And there was the incandescent Raúl Carballeira—whom he may have loved most of all, and for whom he penned a poetic eulogy in his book Momentos—who, in 1948, at thirty years old, cornered by the police in Barcelona and wounded in a shoot-out, chose to take his own life rather than surrender. There was romanticism in Federico’s refusal to call himself a revolutionary, yes, and in his tears for his fallen friends, for a dream destroyed, but it was not mere romanticism—there was authentic historical experience, and spirit and humanity and truth in it.

And he could be excessively judgmental, but his wrath was often directed at a failure he perceived in people, then and today, to forget the most important truths of life—that, as one of his heroes, Lev Tolstoy, put it, that “the supreme law of life is love,” and as another, Emma Goldman, put it, that “Life without an ideal is spiritual death.” He was fond of quoting both. His orientation was always existential and ethical. He never succumbed to spiritual death. He was always being renewed by el Ideal, forever being born, until the end. And he never lost hope in the possibility of human freedom and solidarity. In an interview with Pacific Street Films in 2003, he said, “Maybe humankind will never reach true freedom, but as long as one single human being is dreaming for freedom, and fighting for it, there will be hope. That’s the thing that keeps me alive.” (See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHHchKNfgM4.)

* * *

Born in Barcelona in 1920 in an anarchist immigrant family that had come to the city from the Castilian hinterland to work, Federico grew up in the heavily anarchist, working class Barcelona district of Clot, a barrio that has continued in its own way to represent the famous Barcelona rebelde, even recently, in the last few years of asambleas (community assemblies) and the indignados, who played a role in inspiring our Occupy movement. He had two brothers and two sisters, all older, who had been born in the village of Uclés, in Cuenca province. Federico was able to visit the village in 1988; he told historian Paul Avrich in an interview for the book, Anarchist Voices, that at the end of the Civil War, Uclés, where a Republican hospital had been located, fell to Franco’s troops and was converted into a concentration camp. The mass grave of the starved and murdered prisoners is still there.

Federico’s father, Santos Arcos Sánchez, and his mother, Manuela Martínez Moreno, had been peasants; his father was illiterate, and his mother could read and write only a little. Federico learned to read across the street from his home at the Academia Enciclopédica, one of the anarchist free thought schools that provided a broader educational experience than the vast majority of schools available in Spain at the time, most of which were sponsored by the Catholic Church. One of his earliest memories was reading the workers’ newspapers to his father and other neighbors when they gathered in their doorways to socialize at the end of the day. He left school at thirteen and started working as a cabinetmaker, becoming an apprentice at fourteen. He later went to trade school and became a skilled mechanic, working on lathes, drills, cutters, shapers—he would continue to work in this field throughout his life. At fourteen, he also joined the Confederación Nacional de Trabajo (CNT), the anarchist union. His father, brothers, and brother-in-law were all CNT members.

Federico often talked with great emotion about the working class community in which he was formed. In an interview for the 1997 film Vivir la utopia (Living Utopia), he recalled: “Neighbors made up one big family. In those days there was no unemployment benefit, no sickness benefit or anything like that. Whenever someone was taken sick, the first thing a neighbor with a little spare cash did was to leave it on the table … There were no papers to be signed, no shaking of hands … And it was repaid, peseta by peseta, when he was working again. It was a matter of principle, a moral obligation.” Thus to us Federico served not only as a link to the glory days of the revolution, but also to that older village society of solidarity and mutual aid, to the community described by Kropotkin, the soil in which the revolutionary communitarian ethos came to life.

In 1936, the people of Barcelona rose up spontaneously and quickly put down the fascist coup locally. There were some skirmishes with a handful of pro-Franco rebels, some bombs were thrown, the workers began to take over industry and run the city, and brigades to defend the city were formed. In Vivir la utopia, Federico recalled: “It was as if the whole of Barcelona was pulsing to a single heartbeat, the sort of thing that only happens maybe once in a century … And, if I may say so, it has left its mark on my life and I can still feel that emotion.” Federico joined the Juventudes Libertarias of Catalonia and volunteered to fight (at first he was not taken because of his age). He recalled that when he saw anarchists burning money, he decided to save a few pesetas to show his children so that he could tell them, “Think of it, people used to kill one another for money!” He had just turned sixteen years old. He and other youths formed a group, Los Quijotes del Ideal (the Quixotes of the Ideal), named after literature’s greatest idealist, and began publishing El Quijote, which was censored by the Republican government for its stubborn anarchist positions. He and other young people were critical of the CNT for joining the government; they admired the Durruti Column, where everyone including Durruti received the same pay and officers were elected.

In April 1938 Federico was sent to the front near Andorra, along with his brother-in-law and mentor Juan Giné. Durruti was dead, and things were moving in the other direction, but Federico did not turn his back on the struggle. He recalled that when he got to the front, he ran into an old friend who had no shoes, and he gave him his second pair of alpargatas, the cheap cloth slippers worn by the poor. He was appointed a miliciano cultural, and he found a blackboard and an illustrated two-volume set of Don Quixote, and used both to teach the troops to read and write. He was issued a rifle and bayonet, did night watch, and slept in his uniform. “Mice chewed away at my pants,” he told Avrich, adding that the Republican army’s “equipment and clothing left much to be desired.”

I think of that gift of a pair of alpargatas, the salvaged blackboard and beautiful edition of the Quixote, and of the mice chewing at his clothing like the mice in the cell of Diogenes, as illustrative of the struggle of culture and life against terrible inhumanity. Federico carried that world—the great suffering (el dolor), but also the fraternity and beauty—in him. He imparted that world to us by his witness and his warmth.

In November 1938 Federico was deployed to Tortosa, a once beautiful town that lay in ruins on the lower Ebro River, southwest of Tarragona and Barcelona. The fascists were winning the battle. Food was scarce, though there were oranges from the groves around the town. Soon, Republican forces were overwhelmed by Franco’s troops, and retreated in disarray to Tarragona. Then Tarragona fell. It was a rout, with planes strafing the fleeing columns; the dead—men, horses, and mules—lay scattered along the road. “My comrades were dying all around me,” he recalled. He himself was wounded slightly by a piece of shrapnel. (Some of the story of the collapse of the Republican front, the fall of Tarragona and Barcelona, and the flight to France is told in Avrich’s Anarchist Voices, and more detail is given in the Spanish edition, translated by Antonia Ruiz Cabezas, Federico’s good friend and ours.)

In February 1939 Federico and some of his close compañeros made their way out of Spain and into France in a harrowing passage through the mountains. They were sent to a series of refugee camps, where people made the best of their situation, organizing cultural events and creating a school where they taught each other French, math (both of which served him later), and other subjects. His closest Quijote buddies—Germinal Gracia, Liberto Sarrau, Diego Camacho, Raúl Carballeira—made their way there, too. In the Spanish edition he says of that time in the camp, “We formed a true community, united by the Ideal and love. Those moments make up part of something very intense that endures across the years.”

Federico left the camp in November 1939 to work for a time in an aviation factory in Toulouse, until the defeat of France in June 1940, when he returned to the camp at Argelès. In 1941 he escaped from the camp; the Vichy government was deporting the Spanish refugees to slave labor camps in Germany, where thousands would die, and by 1942 German troops were directly in charge of the area, seizing and deporting people to the camps. He hid in Toulouse, working in a factory for a sympathetic employer. By 1943, things had become so dangerous that he and others decided to return to Spain, which was calling on exiles to return and report for military service. Upon his return, he was jailed and then pressed into military service, and sent to Morocco, to Ceuta and the same barracks his father and brother had been sent earlier. He remained there for two years.

Federico was lucky in Morocco. He learned some Arabic and he read a lot. Once, after he told the commander he wouldn’t go to church or take communion, the man did him a good turn, assigning him to guard duty on Sunday mornings and later offering him a post at a checkpoint in the mountains, away from the barracks, and where it was quiet and the air was clear. He thought Federico the best man for the job because they needed someone at the checkpoint who would not be afraid to demand that military officers follow the checkpoint protocols like everyone else. Federico’s defiance thus worked for him. He also liked to tell a story about how the portrait of Franco that hung in the barracks kept mysteriously disappearing, to the consternation of the commander. They could never catch anyone, and eventually they stopped hanging it in there.

In 1945, he was released from the army and returned to Barcelona, where he reunited with some of his old comrades, and started working with the underground, including working on the clandestine paper. He left for France in 1948 after the death of Raúl Carballeira, later crossing back into Spain with other militants and robbing a factory in the Pyrenees to turn the funds over to the movement. He was nearly captured, and almost froze to death in the mountains, before returning to Toulouse.

His close friends Liberto Sarrau, Diego Camacho, and Germinal Gracia were eventually all arrested. Diego, who had been pressed into forced labor by the Nazis in France, eventually worked with the French resistance and then the Spanish underground. He was arrested and imprisoned twice, from 1942–1947 and then almost immediately after being freed, from 1947–1952. He took shelter in France until 1977, after the death of Franco. As Abel Paz, he authored many books on anarchism and other subjects; he died in Barcelona in 2009. Liberto was arrested in 1948 and sentenced to twenty years, but was released after ten. He moved to France and remained active until his death in 2002. Germinal, who used the pseudonym Víctor García, who had already escaped from a cattle truck transporting Spanish prisoners to Dachau in 1944, managed to get out of jail using false identity papers after being arrested in 1946, and after a shoot-out with police later fled to France. In 1948 he went to Venezuela, where he edited the anarchist publication Ruta, and also from where he traveled all over the world, earning the title “El Marco Polo del Anarquismo.” He died in France in 1991.

Federico stayed in close contact with them all—their friendship was deep and unwavering. These men, and so many other men and women of the anarchist community, were remarkable, admirable human beings. We consider ourselves to be extraordinarily fortunate to know of them and to have gotten to know some of them.

* * *

In 1952 Federico immigrated to Canada and began working at a Ford auto plant in Windsor as a skilled mechanic. In 1958 he became a Canadian citizen and was also reunited with his companion, Pura Pérez, who had been in the group Mujeres Libres (Free Women), and who came with their daughter Montse to Windsor. Federico worked much of his life at Ford, and was a militant rank-and-file union member, participating in the historic 110-day Canadian Auto Workers strike in Windsor in 1955. He brought his experience and his broad understanding to the factory floor, union hall, and community. He was highly respected not only for the ideals he espoused but for his cosmopolitan humanity, his day-to-day principles, his commitment to and hard work for his fellow workers. He was also known to point out, with a certain ferocity, that the union was a human institution built to provide mutual aid to the workers and to advance the cause of an international that would be the human race, not a business guild created to carve out a bigger piece of a pie based on the assumed cynicism and corruption of all. Similarly, he was quick to remind the uninformed or the mendacious, which he did on multiple occasions at meetings and conferences on the history of the Spanish war, that Spain first had a Revolution, and then a Civil War, and that many of the purported good guys in the Hemingway legend and related Civil War tales were not as good as they were made out to be.

After he retired from Ford in 1986, Federico became a committed volunteer with the Occupational Health Clinic for Ontario Workers and the Windsor Occupational Health Information Service for more than twenty years, collecting information and educating workers on the dangers of industrial chemicals to workers and the larger community. With these organizations, he also used his Spanish as a volunteer to help Mexican migrant workers on Ontario farms. As with his CAW work, he proved that he could overcome ideological differences for some greater good, working pragmatically for the sake of people in need with people who did not necessarily share his anarchist ideas, even, God forbid, with a man who, he told me, was a Catholic priest, but nevertheless a good man and a real human being. Some of our anarchist friends in Spain have joked with us about the older generation, that “Se les pararon los relojes al cruzar el Río Ebro” (Their watches stopped when they crossed the Ebro River), but in Federico’s case this was not true; the old truths lived on in him, but he was able to allow them to evolve with his experience as life went on. For this reason, too, he was a voice of reason—unsuccessfully, it turned out—when the Spanish CNT imploded due to sectarian in-fighting and political gangsterism.

During his time in Windsor, Federico also found what remained of a vibrant anarchist community across the river in Detroit—Spaniards, Eastern Europeans, and Italians—people we would eventually meet through him. In the 1970s he met Fredy and Lorraine Perlman, became a supporter of and collaborator on their publishing project, Black and Red, and met us at the Fifth Estate, becoming an active supporter and volunteer. Federico had been one of the youngest members of the European immigrant anarchist community. After he found us, he gradually became one of our most cherished elders, our abuelo, our yayo.

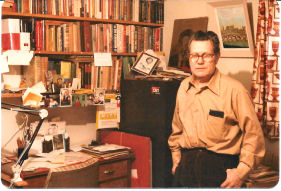

When we met him he was already putting together what became one of the foremost anarchist archives in North America, indeed, in the world, in his modest Windsor home. Many scholars, most of them sympathetic to anarchism, would go to the Labadie Library at the University of Michigan to do research, and then cross the river to visit him, and do their research there in his archive in the basement. He is thanked in numerous books, articles, and blogs by historians and radical activists who came to work there or simply to meet him and his compañera, Pura. Visitors were always welcomed and fed in the typically gracious Iberian style, often with a delicious paella he would tell you was Catalan, and Pura would tell you was Valencian. We, too, spent many fascinating and pleasant afternoons around their table. We appreciated his romanticismo, and also how she tempered it with some biting commentary on the foibles of Spanish anarchism. He would be telling some heroic story about Durruti, and she would remind him that while the CNT and FAI men were in the dining hall eating and giving speeches about the libertarian ideal, the women were cooking in the kitchen (where, given the windy rhetoric, they generally preferred to be).

Pura had been a nurse in Spain but as it sometimes happens with immigrants, she only worked as a nurse’s aid in Windsor. Federico had had almost no formal education, only his apprenticeship and the anarchist ateneos and academies, which ended when he was thirteen or fourteen, and then his reading and voluminous correspondence. And yet they were deeply cultivated people—both of them prolific readers, poets, and activists who loved the arts and embraced enduring human ideals. Pura left notebooks of beautiful hand-written notes copied from art textbooks, made beautiful arrangements of dried flowers, and wrote formal poetry. Fede read and wrote poetry, and loved music and art, film and history.

He could also be funny. He’d put a finger on your shirt button, and when you looked down he would bring it up and catch you on the nose. If someone was blathering at him, he might fire off one of his famous lines, Los vagones de tus necedades resbalan por las rieles de mi indiferencia. (The train cars of your foolishness are sliding along the rails of my indifference.) He would raise his arms sideways and invite you to tickle his sides, and if you did he’d box your ears. He did this with men and boys. With women it was a little different. Even when he was on his last legs in the hospital he still had a way of coquetting with the nurses without offending them, while needling me and another male visitor.

Federico wrote many reports for the anarchist press in Spanish and French, and in English for his union newsletter. He authored a monograph on Tolstoy and other essays on a variety of subjects (including two brief, lasting reflections on anarchism and the human condition, “‘Man’ and His Judge,” and “Letter to a Friend”). He carried on an active correspondence and wrote many eulogies of comrades. (I found two of his eulogies that were published in the Fifth Estate: “José Peirats: A Comrade, A Friend,” in the Winter 1990 issue, for one of Federico’s closest mentors and friends, author of Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution and many other books; and “Germinal Gracia: The Marco Polo of Anarchism,” in the Winter 1992 issue, which contains not only rich material on Gracia but also vivid memories of the internment camps in France and the libertarian anti-Franco underground.)

* * *

Federico’s love of poetry led him to produce Momentos, a small collection of his poems, in 1976, with elegies to his fallen comrades and meditations on the human condition. The poems are modest, and sometimes too sentimental (he grew up reading late romantic poetry, and the effect can be felt.) Yet at times, in some surprising moments of simplicity and honesty, one feels as well the influence and emotional depth of great early twentieth century poetry—the Machado brothers, León Felipe (whose work he admired), the Generation of 1927, and perhaps the ancient oral traditions and romances, too. In his practice of a poetry both simple and reflective, he was typically Spanish, typically Iberian.

In Federico’s poetry one feels, inevitably, the grief, the failed dreams, the surge and pull of hope and despair, and the sense of humility and awe at life’s inherent uncertainties:

No se puede contar You can’t count

el infinito infinity,

ni concebir nor conceive of

la eternidad; eternity;

pero hay realidades but there are intangible

intangibles realities

que no podemos we cannot

ignorar. ignore.

Simple, yes, but also admirable that in his poetry a question is worth far more than an answer.

Or where he has an answer, it’s existential and personal:

¿Qué es un día? What is a day?

¿Qué es un año? What is a year?

¿Qué es una vida? What is a life?

Nada. Nothing.

¿Qué es un recuerdo? What is a memory?

Toda un vida. A whole life

Perhaps because I knew him, these poems mean more to me than they would to a stranger. They might not weigh as much on an academic’s scale. But to me they are profound. Federico was deeply spiritual; he accepted “intangible realities”—an ideal of human solidarity, love for one’s brothers and sisters, self-sacrifice, dying for something that seemed impossible. And a memory, for a man who lived in and with his memories of revolution, of solidarity, of courageous self-sacrifice, and who with great devotion collected documents of memory so that others might know of these human ideals—what was a memory? Toda una vida.

Many people who met Federico or learned about him have written about their admiration for him. To give one example, the poet Phil Levine was one of Detroit’s most beloved sons (and an anarchist sympathizer—see his wonderful book, The Bread of Time, where he writes about anarchism and Spain). A number of years ago, after Levine read his work in Ann Arbor, I gave him a copy of the Fifth Estate with Federico’s “Letter to a Friend.” Levine later wrote to me, calling the essay “extraordinary” (which suggests that if a poet of Levine’s stature saw poetry in Federico’s writing, it can’t be only my sentiment working when I see it). He added, “You truly sense the depth of this man’s goodness & why he has come to a vision in which the things of the earth are shared by all. I showed it to my wife and she was overwhelmed by it. Unlike Pedro Rojas in the poem I read by Cesar Vallejo [at the poetry reading in Ann Arbor], this Federico has gotten to the meaning of things. (Vallejo describes Pedro seized by the killers ‘just as he was getting to the meaning of things.’ Most of us are at best getting close all of our lives; Federico arrived.)”

Many others who knew him, both slightly and well, have written about him with admiration and affection. In a tribute to Federico, Anatole Dolgoff, son of the respected Russian-American anarcho-syndicalist Sam Dolgoff, wrote that just about the last thing his father did when he was dying was to call Federico and say farewell, and carry on. The younger Dolgoff (who became a good friend of Federico’s in his own right) adds, “Russell Blackwell, a dear friend of my father and a neglected figure in the history of the movement—a man who had fought on the side of the CNT during 1937 May Uprising in Barcelona, who had been arrested many times and tortured by the communists, who had come within an inch of being executed by them, and barely escaped—took one look at Federico, and said, ‘This guy is the real thing!’” Anatole added, “Is there a human being privileged to know Federico who can think otherwise?”

* * *

One of Federico’s most vivid stories was from after the fall of the Spanish Republic in 1939, when the refugees were crossing the Pyrenees into France, ill and exhausted, some wounded—all dispirited, all unsure of the future. They were also weak with hunger; Federico told us on a number of occasions with a kind of wonder how they gathered acorns under the oaks to eat and how they were sustained. He added (a comment that appears in the Spanish edition of Anarchist Voices), “How bitter those acorns were!”

Those who have read Don Quixote will likely remember that since classical times the oak tree has been a symbol of the Golden Age. Behind young Fede Arcos, not yet nineteen years old, lay the ruins of one of history’s brief Golden Ages, and one of the most sublime dreams human beings have dreamed. Those acorns were indeed bitter. Ahead lay great uncertainty—and we know now, more violence, more calamities and defeats. But the people who had fought for a new world gathered and ate the acorns and were sustained. May their dream sustain us, too. Federico Arcos lived a life of passion and commitment with that new world always in his heart, reminding us, as Rousseau once remarked, that the Golden Age is neither before us nor behind, but within. Like others of his generation, he proved by example that one may lose great historic battles, and yet triumph in life.

Federico always seemed to think that he had fallen short of the people who had made the ultimate sacrifice, but he served the cause of freedom, and of historical memory, honorably and ably. His participation in the revolution and his devotion to documenting el Ideal were both admirable accomplishments. At the end of his life, he was able to donate and ship his life work to the Biblioteca de Catalunya in Barcelona (the National Library of Catalonia). The archive amounted to some ten thousand books and documents, many of them previously unavailable in Spain. (See http://antigua.memorialibertaria.org/spip.php?article1347.) A friend in Barcelona wrote to me recently that people were astonished and thrilled at the wealth of materials it offered, and not just Spanish documents but also the American materials he had gathered. Other documents and artifacts can be found at the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan. (See http://www.lib.umich.edu/blogs/beyond-reading-room/anarchists-suitcase-honor-federico-arcos-1920-2015.)

In the last weeks and days of his life, Federico suffered, disoriented and depressed, in the hospital and then a nursing home, either one an unhappy place to end. At almost 95, life and death converging in him, he was naturally a tatter of what he had been. He raged, and fought the current.

When like Lear in his storm on the heath, you have nothing left and almost nothing remains of you, you may find yourself reduced to what you once truly were, and what you wished to be. And so we were struck by what someone at the nursing home reported: that late in the first or second night he was there they found him sitting at the bedside of another inmate, who was unconscious; Federico was holding his hand, comforting him and watching over him, like a comrade at the front.

The supreme law of life is love, said Tolstoy. Federico Arcos had that love in him. And his love, like his dream, will sustain us, will remain with us.

So, another toast. Federico Arcos, presente. ¡Salud y libertad!

This is a revised and expanded text of David Watson’s contribution to the remembrance for Federico Arcos at the Cass Café in Detroit on July 19, 2015.

See also:

“Federico Arcos Dies at 94” by David Watson (FE 394, Summer 2015)

French translation: http://acontretemps.org/spip.php?article591

Momentos: compendio poético by Federico Arcos