John Clark

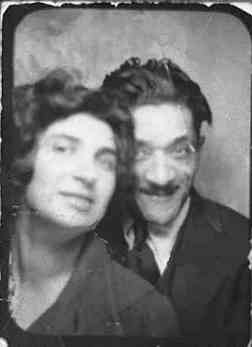

Sam Dolgoff

A Life at the center of American anarchism for seventy years

a review of

Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff by Anatole Dolgoff; Introduction by Andrew Cornell. AK Press, 2016, 391 pp., $22.

Anatole Dolgoff is a great story-teller. He does the kind of writing that is rare on the left. It never seems to occur to most political writers that entertaining people is not a bad thing. It occurs all the time to Anatole.

In this fascinating combination of biography and people’s history he manages not only to inspire but to entertain. He has a deep appreciation of all the humor and irony, along with the joys and sorrows, of real life.

This wide-ranging narrative testifies to the author’s love of his father, his mother and his family. In addition, his deep affection for people, from the quite ordinary to the sometimes very extraordinary, comes through powerfully. There is a lot of suffering, pain and even tragedy in this story, but what wins out ultimately is humanity and compassion, humor and inspiration.

During his lifetime, I knew Sam Dolgoff (1902–1990) through his important books, Bakunin on Anarchy, The Anarchist Collectives and The Cuban Revolution: A Critical Perspective, all of which I recommend highly for their insights into three crucial periods in anarchist history, and also through his role as a major figure in the IWW and the anarchist labor movement.

His son describes Sam as “a house painter, a loving husband and father, a militant labor organizer, a powerful orator, and a self-taught public intellectual.” He says that throughout his life Sam “stuck to his bedrock beliefs that humans were capable of cooperating with one another, managing their own affairs, and sharing earth’s wealth equitably.”

Notice that Sam’s beliefs are not primarily political doctrines or sectarian dogmas, but rather expressions of a basic faith in people, their capacities, and their fundamental goodness.

Sam Dolgoff is at the center of this book, but it’s also a book about Sam’s World and all the people who populated it. Anatole says that Spanish anarchist militia leader Durutti’s famous dictum, “We carry a new world here, in our hearts,” was “the essence of Sam Dolgoff.” The book helps reveal that new world to us by showing how many have lived it, in the here and now, in their own lives.

This book is also a history of the 20th century anarchist movement, the immigrant and especially Jewish anarchist movement, the IWW, and the radical labor movement. Those of us who have been members and supporters of the IWW will appreciate the central place it has in this story.

Anatole remembers the “joy he felt as a small boy” when is father announced, “it was time to visit the Five-ten hall.” This was one of the few remaining IWW union halls, where he met many old Wobblies and heard stories of radical labor history first-hand.

He puts a very human and personal face on this history and shows how the union was not only a labor organization, but a strong community of mutual aid and loyalty between comrades. He sketches a vivid portrait of life among the Wobblies, from dedicated activists and self-sacrificing revolutionaries to assorted jokers and characters. Along the way, we learn much about the concrete meaning of solidarity.

It is an important work for its contribution to helping correct the lack of attention in anarchist studies to the reality of the distinctive spirit of the era and milieu. It reminds me in some ways of Tom Goyens’ Beer and Revolution, a scholarly work, but also one that is unusually concrete in recounting the details of the everyday life of the German immigrant anarchist community of New York City

Goyens depicts a popular culture in which neighborhood life, beer parlors, picnics in the country, bands and orchestras, in short, sociability was so important. Anatole’s book is also rooted in this way in everyday life. It helps us understand why more readers have been drawn to anarchism through the pages of Emma Goldman’s novelesque autobiography, Living My Life, than by thousands of manifestos and treatises that are certainly full of excellent ideas, but are often lacking in the “life” part of it. Left of the Left carries on this tradition of presenting anarchism as a form of life, a way of living.

Readers who have been drawn to anarchism through the counterculture, through Punk music, through radical ecology, through ecofeminism, or through the global justice movement, will get something very important from this book. It will show them that their own movements are related to a long and very rich history of struggle and organization that has largely been forgotten over the past generation or two.

It offers something that few contemporary readers, whatever their anarchist or radical sympathies may be, will have experienced: what it was like to grow up in an anarchist family, an anarchist community and an anarchist culture.

Anatole recounts quite a few feuds and arguments among the anarchists themselves and within the larger left. He finds that Sam was often, in fact most of the time, correct, but he doesn’t mind admitting there were also a good number of cases in which Sam’s judgment was a bit off

Though Sam was not one to hold grudges, he could be rigid in his thinking at times, while Anatole is much more willing to give people slack and consider the validity of different ways of looking at things, even on highly contentious topics such as the collaboration with the state by some Spanish anarchists during the Civil War and social revolution.

He doesn’t avoid ideological issues, but he discusses them within a larger narrative that includes rich historical and personal detail. There are long sections on such important figures as the prominent Russian anarchist, G.P. Maximoff, the legendary Italian-American anarchist leader, Carlo Tresca, the African-American IWW hero, Ben Fletcher, and the revered Communist-turned anarchist Spanish Civil War veteran, Russell Blackwell.

The sections on Maximoff show the kind of important details that can be learned from this book. Maximoff was Sam’s mentor, and he admired him greatly, both as a movement figure and as a theorist. His book, The Political Philosophy of Bakunin: Scientific Anarchism, is one of the best-known works on Bakunin’s ideas. Yet, Anatole shows how Sam, despite his high regard for Maximoff, pinned down the problem with his version of Bakunin.

Maximoff’s method of plugging short quotations into a systematized framework abandoned any “sense of context and history” and “put Bakunin in a straightjacket.” He artificially molded Bakunin’s often impressionistic and completely unsystematic thought into a “scientific anarchism,” while, as Sam put it bluntly, “there is no such thing.”

I’ll end by simply recommending that you get the book and read it cover to cover. You never know when some amusing incident or fascinating biographical detail will be followed by a revealing glimpse of working class life, or an illuminating insight into anarchist or syndicalist politics.

John Clark is a writer, educator, and communitarian anarchist activist in New Orleans, where his family has been for twelve generations. His most recent book is The Tragedy of Common Sense, available from ChangingSunsPress.org.

Dolgoff on National Liberation

Sam Dolgoff quoted in Left of the Left on the establishment of Ghana in 1958 as an independent state which the left celebrated as “progressive:”

Behold! A new state is being built! The power of foreign colonial rulers is now wielded by the new government. The new government makes and enforces the law of the land. It creates the machinery of domination. It organizes the army, police, jails, judge, courts, schools, radio stations....

To the native governing class, independence meant the right to abolish the natural, social, cultural and communal institutions that were developed by the people, and impose from above, by force, an artificial scheme of life, which nullifies or distorts their natural development and paralyzes their creative capacities.

The new rulers secretly admired the colonial government and administrators. They envied the easy, luxurious life of their masters, their power, their prestige....They soaked up the teachings of their master like a sponge absorbs water.